THEWHITEBOX

TLDR;

A few weeks ago, we discussed the situation between the US and China from the hardware and infrastructure perspective.

Today, we take a look at the software side, why compute budget matters a lot, the market concerns in China, the trick Chinese Labs use to appear close despite not being close, the product moat, and what China will try to do in a situation of comparatively low access to compute to keep up the battle.

We will end with a series of insights that summarise how you should think about the US vs China AI war in 2026.

Together, we’ll learn that comparing the US and China solely based on chip specs and AI model benchmark scores is something only rookies do.

Let’s dive in.

We have bayonettes, they have tanks

To explain China’s software decisions, we need to recall the sources of its issues. And while there are very few things in this world that China is starving for, one of them could be instrumental in determining who wins the AI race: compute.

Summary of what we discussed

Without going into too much detail because I already did, one of the key takeaways from the previous piece was the serious struggles China was facing to keep up with the US in accessing compute, having a production capacity in the order of 50 times less than what the US and Allies can produce (in fact, it’s mostly a comparison with the US/Taiwan/Korean combo).

But why is this so important?

Unless algorithmic improvements change the paradigm completely, currently, there are two ways you make progress in AI:

Increase compute training budget: Training larger models on larger datasets for longer, also known as the first scaling law.

Increase inference-time compute budget: Let models use more compute per task during execution.

As you can see, the common denominator is the need for more compute both for training (first scaling law) and for inference (second scaling law).

Compute. Compute. Compute.

“The truth may be that the gap is actually widening,” Tang Jie, founder of the Chinese AI startup Zhipu, said at a conference last weekend in Beijing.

Alibaba’s head of development of the Qwen model family gave them a “20% or less” chance of beating OpenAI or Anthropic over the next three to five years.

But then, why are we seeing the media saying China is closing in, that in some respects it’s ahead, yadda yadda yadda? Besides the media being as clueless as always, they have reasons to believe this because they are looking at it from the wrong perspective.

Reframing what is measured

Isn’t China releasing models that appear as smart as US ones? When you look at popular benchmarks, they are very close on many scores (e.g., three in the top 10 of Artificial Analysis main intelligence benchmark), and handsomely leading the way when only comparing open-source models.

Furthermore, Jensen Huang has said that China is “nanoseconds behind”.

Not surprisingly, the media and investors circle around this idea. Well, wrong, because we are looking at this from the totally wrong framing. Let’s explain why this is one of the biggest lies we are being told.

Listen, AI software is a commodity today. It just is. This means that the know-how to build frontier AI models isn’t geographically concentrated in a bunch of Labs in the US. DeepSeek’s researchers know just as well as OpenAI researchers how to build powerful models. If anything, the moat is in the product.

But what is an AI product? Simply put, it’s just code sitting on top of Large Language Models, or LLMs.

ChatGPT is an AI product because it lets you interact with LLMs in several ways. So is Claude Code in a similar way. And so is Cursor, which offers a set of harnesses that allow you to get the most out of LLMs for coding.

Therefore, an AI product is the result of AI models, the harness, and compute. US Labs have exactly zero moat in the first two, but the third one is another story.

As we saw earlier, “AI progress” is determined by how large your training run was and by how much effort your AI models can devote to any given task. As China has much less available compute, this translates to two facts:

Chinese models are way smaller and have been trained for much less time (measured in GPU hours).

Chinese Labs deploy much less inference-time compute per task

Consequently, when deploying these models to users, the gap between the US and China widens, particularly in inference-time compute, which is probably the biggest performance lever today.

But while the inference-time compute gap is self-explanatory, we haven’t explained how on Earth China manages to get similar lab results and benchmark scores at the model level if Chinese training budgets are much smaller?

And the answer is the other illusion Chinese Labs play on everyone.

Distillation, the best trick in the book

There are two popular ways you can train a frontier AI model: from scratch or via distillation.

From-scratch training is the idea of starting with a model that knows absolutely nothing and guiding it through the entire learning process. This takes an enormous amount of time and effort; to the model, everything is new, and external guidance is literally zero.

This is how US Labs train the larger models, the ones they intend to lead to the next leap in intelligence.

On the other hand, distillation is a similar process but includes a small caveat: there is teacher guidance.

In simple terms, distillation is a teacher-student method in which the student not only learns through their own effort but also receives guidance from a more knowledgeable teacher.

Using a human analogy, from-scratch training is like taking a newborn baby, locking it in a room full of books, and letting it learn on its own via rote imitation of Internet-scale data. On the flip side, distillation includes a teacher in the room who provides guidance.

But what do we mean by guidance here? There are two ways Labs use distillation: soft and hard.

Soft distillation is just generating data from a superior, teacher model and training the student on that data, just like you would on other data. The point is that this data is of higher quality than what you might see on the open Internet and has a much larger scale than what a bunch of researchers can generate on their own.

Conversely, hard distillation forces the student to generate in the same way the teacher does. In other words, we are literally forcing the student to imitate the teacher’s distribution. More specifically, we sample both models and measure the student’s predictions in two ways:

How correct each prediction was

How similar the student's response is to the teacher's response.

Using our teacher-student human analogy again, soft distillation is the teacher giving new data to learn from for the student to imitate, while hard distillation is getting the student to respond while the teacher giving their opinion “I would have responded this way,” meaning in hard distillation there’s active, online participation by the teacher model in every prediction (making it much more expensive).

Technical clarification: Hard distillation adds a KL divergence term so that the student model is not only rewarded by making the correct prediction, but also by ensuring that the output distribution (how all the words the student has considered as candidates are distributed) is similar to the teacher’s, thereby becoming essentially a “watered-down” version of the teacher.

If the teacher considers “Washington” as the most likely prediction to the USA’s capital, “New York” second and “Los Angeles” third, the student should get that distribution as similar as possible too.

And why am I telling you all this?

Well, because I have a firm belief that soft distillation is the “secret” that allows China to “keep up” with the US. Chinese AI Labs are generating huge amounts of synthetic data from US models and using them to train their models. Nonetheless, OpenAI accused them explicitly of this.

The point here is that, as I explained earlier, this allows smaller models to “behave” like larger ones and thus “appear” as smart as their teachers, because, well, they are literally trained to imitate them.

The problem with distillation is that, as always, there’s no free lunch here. Distillation implies that, while it pulls the student close to the teacher in benchmark performance, it is very unlikely, if at all, that the student can “surpass the master.”

If you’re trained to imitate someone, it’s very unlikely you surpass it unless you start doing something else beyond imitation, because the teacher’s teachings represent the upper bound of what you can learn.

That is a very probable reason why Chinese models appear very close to US counterparts, but never quite ahead, unless for minor benchmark results or in tasks that US Labs have clearly not prioritized.

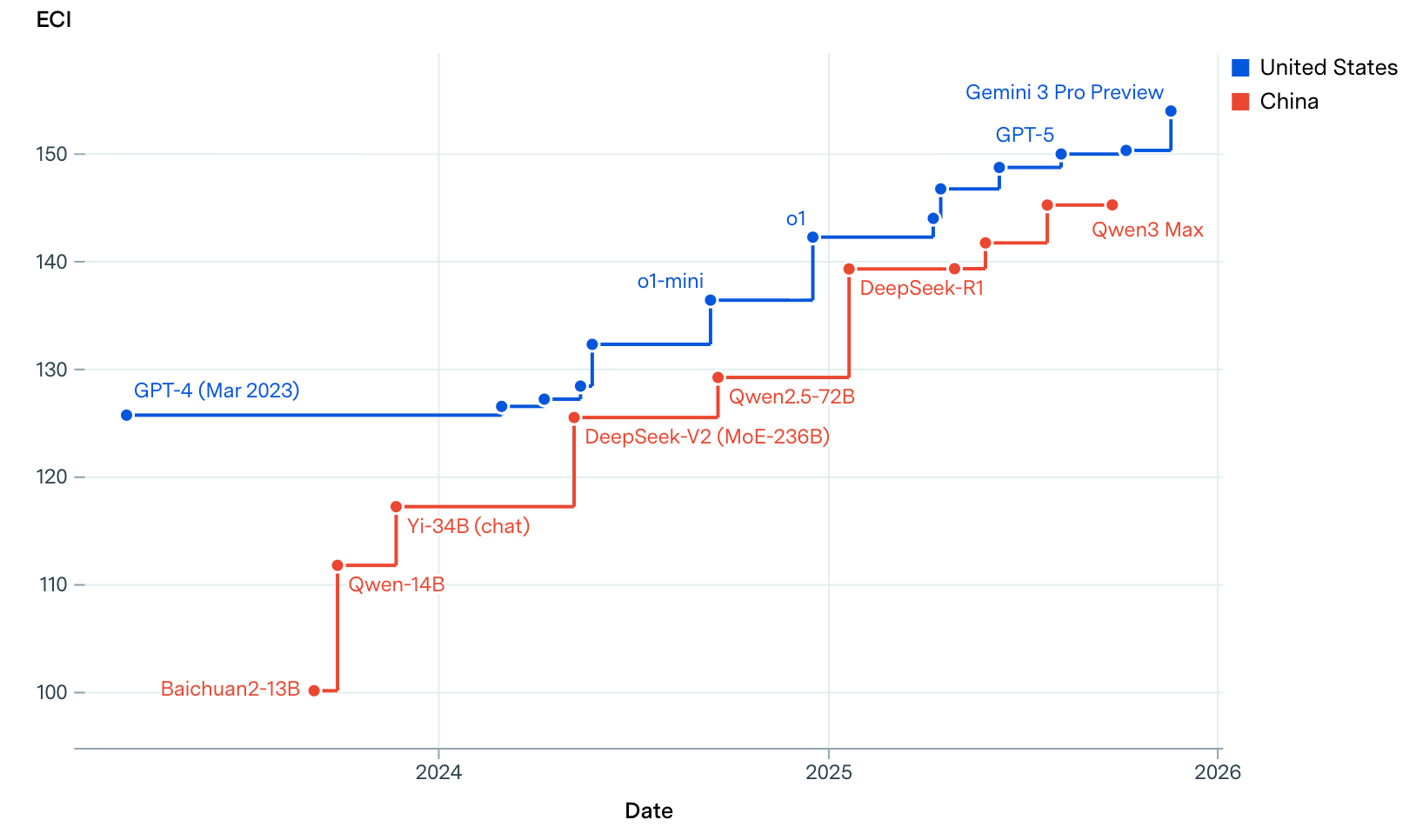

Source: EpochAI

So, what does all this mean?

Let’s be real

Just like sailors hallucinate boats while stranded on beaches, the idea that China is close or ahead is mostly an illusion placed on all of us due to the fact that we are looking at this competition the wrong way, models instead of products, and also via the effect of soft distillation that makes Chinese models appear closer than they really are.

At the end of the day, everyone agrees (including Chinese researchers) that compute is the determining factor and that scaling laws remain unavoidable.

Also, it’s not like the Chinese Labs have a totally different recipe for training AI models (we know because they open-source everything), so there’s no “magic recipe” here, and the world is still ruled by whoever deploys the most FLOPs.

So, is all hope lost for China? Of course not, but not for the obvious reasons.

Subscribe to Full Premium package to read the rest.

Become a paying subscriber of Full Premium package to get access to this post and other subscriber-only content.

UpgradeA subscription gets you:

- NO ADS

- An additional insights email on Tuesdays

- Gain access to TheWhiteBox's knowledge base to access four times more content than the free version on markets, cutting-edge research, company deep dives, AI engineering tips, & more