THEWHITEBOX

US-China War Guide for 2026: Part One

Welcome back and Happy Holidays! This week, I’m bringing to you the most thorough analysis of the US and China I’ve ever made.

It’s a very long article (to cover for my more inconsistent delivery lately, due to the mix of Christmas and JP) that covers everything you need to know about the state of the AI War between the US and China.

We cover everything, literally. Single-chip vs. system-level comparisons, efficiency metrics, supply chain shortages, geopolitical maneuvers, critical bottlenecks, and others; all that’s needed to make up your mind about the state of both countries, and ending with the most important question now that the next year is around the corner.

What to watch out for in 2026? Let’s dive in.

This entire report has more than 14,000 words, so I’ll do it in two parts: hardware for today, software next week.

But what can you actually DO about the proclaimed ‘AI bubble’? Billionaires know an alternative…

Sure, if you held your stocks since the dotcom bubble, you would’ve been up—eventually. But three years after the dot-com bust the S&P 500 was still far down from its peak. So, how else can you invest when almost every market is tied to stocks?

Lo and behold, billionaires have an alternative way to diversify: allocate to a physical asset class that outpaced the S&P by 15% from 1995 to 2025, with almost no correlation to equities. It’s part of a massive global market, long leveraged by the ultra-wealthy (Bezos, Gates, Rockefellers etc).

Contemporary and post-war art.

Masterworks lets you invest in multimillion-dollar artworks featuring legends like Banksy, Basquiat, and Picasso—without needing millions. Over 70,000 members have together invested more than $1.2 billion across over 500 artworks. So far, 25 sales have delivered net annualized returns like 14.6%, 17.6%, and 17.8%.*

Want access?

Investing involves risk. Past performance not indicative of future returns. Reg A disclosures at masterworks.com/cd

Setting the stage

The battle for AI supremacy is being fought on two fronts: hardware and software.

And although we are focusing on hardware today, it’s important to understand that, nowadays, hardware is dictated by AI models, which are improved in two ways, known as ‘scaling laws’.

The first scaling law is increasing model size, thereby increasing training budgets; we train a larger model, which allows us to train it on more data.

The second scaling law is inference-time compute, or deploying more compute on every task.

Using a human analogy, one is training a human with a bigger brain, and the other is allowing them to think more deeply about each task.

In a nutshell, larger and longer thinkers are the way to go. Both are important because they naturally help us understand what is going on in the famous AI buildout.

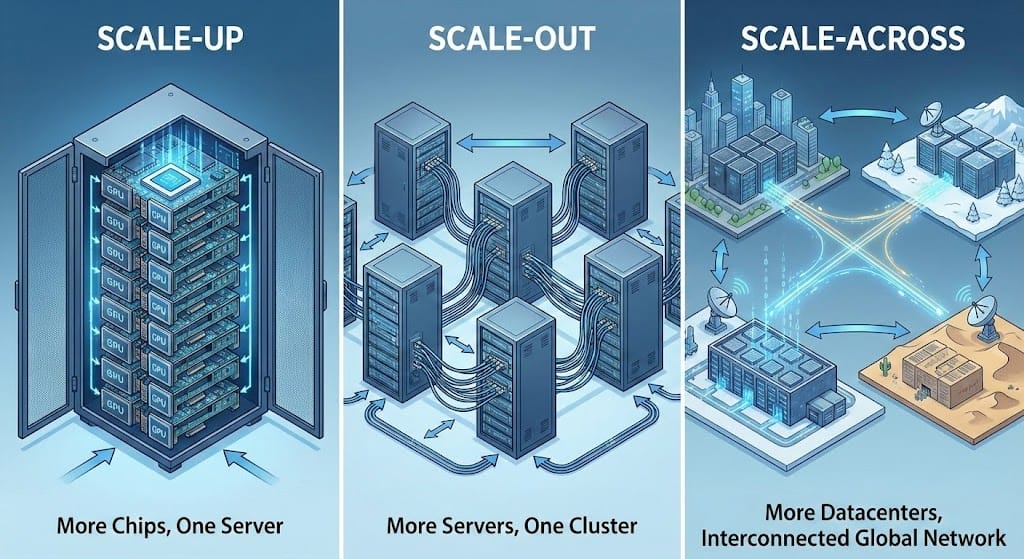

AI hardware scales in three ways:

‘Scale-up’: increasing the number of chips in a single server

‘Scale-out’: increasing the number of interconnected servers, giving you a cluster

‘Scale-across’: increasing the number of interconnected datacenters

And how do each affect both training and inference?

Larger training budgets (training models on more data for longer) dictate how large hardware clusters and data centers get; that’s why data centers are getting so big.

For instance, training a model on a single GPU, even if it’s the most powerful known to humans, the B300, on a GPT-4-level training budget (2022, ancient in AI terms), would take decades (between 35 and 70 years to be more precise).

In other words, what really matters for training is how many accelerators in total you can allocate to a single task, like training a frontier model. It’s not whether each chip doubles performance; what matters is whether you can double chip count, because chip performance grows way slower than what is required today.

On the flip side, inference dictates hardware in another way. A good way to understand this is that, while training only cares about growing chip count, even if that means every sequence is very slow to process, inference is latency-sensitive.

This means that, in an ideal world, inference would be performed on a single accelerator (e.g., a single GPU), avoiding the overhead of communication between accelerators. Sadly, we can rarely do that, but we still desire to be the smallest number possible.

This means inference is intranode, meaning we keep ourselves inside a single server to avoid the extremely slow scale-out and scale-across speeds. If we have more user demand, we deploy more servers with new model instances, but we never scale a single model across two servers.

In a nutshell, software dictates how large servers get. Circling back to the three ways of scaling hardware mentioned beforehand, that gives us:

Scale-up is dictated by inference

Scale-out and across are dictated by training

And when you consider that Reinforcement Learning training, or trial-and-error training, requires models to try several times until they get the correct response, meaning you are running models (inference) during training, this makes scale-up the most essential metric in AI these days (at both ends of the court).

And hardware, long based primarily on improving single-chip performance, is mostly now a game of ‘the one who packs more accelerators into a single server’.

Knowing this, understanding what NVIDIA is trying to do with the next generations now becomes much easier, almost like child's play.

Understanding how hardware is improving

As we said, the primary way of scaling hardware today is through the three metrics discussed above.

This eases the pressure on single-chip performance, which is already running to the limits of Moore’s Law (e.g., from Blackwell to Rubin, the upcoming GPU generation by NVIDIA, transistor density has not doubled as Moore’s Law would have suggested, but has increased by low single digits).

How much is transistor density improving? We don’t actually know, but we can estimate quite accurately.

NVIDIA has publicly described Blackwell B300 as using TSMC 4NP and totaling 208B transistors in a dual-die GPU, while Rubin R100 is widely expected to move to a 3nm-class TSMC node.

Since NVIDIA hasn’t published Rubin’s transistor count and active silicon area, you can’t compute an exact chip transistor/mm² comparison, but you can estimate node-level scaling: using TSMC’s published relative density figures to the 5nm process node as a proxy (about +6% density for N4P vs N5 and about 1.6× logic density for 3nm-class N3E vs N5), the implied logic-density uplift is roughly 1.6/1.06 ≈ 1.5×, or about a 50% improvement. This is an approximation, of course, but you can be confident it’s not doubling, and the lower in nanometers we go, the smaller the jumps will be.

A 50% improvement sounds like a lot, but it’s nowhere near the required pace of progress. Therefore, increasing world size, another way to refer to scaling up, is the way to go.

To prove this point, we can look at Vera Rubin, NVIDIA's upcoming GPU platform. And what all its forthcoming products have in common is that the number of chips on each server is equal to or greater than that of the largest server today, the GB300 NVL72. Later, we’ll see the numbers in more detail as we compare them to China’s offering.

And as we’ll see later, too, Huawei, China’s champion, is heading in the same direction but taking a slightly different and more brutal route.

The other significant hardware change that is directly linked to software is memory. As we mentioned earlier, current AI is improved by making it bigger and letting it think for longer.

Making models bigger means the memory required to store them increases, too.

Letting them think for longer increases their working memory requirements, the memory they need to work with a given user sequence, known as the KV Cache, which not only increases memory size requirements, but also memory speed requirements.

In practice, this makes memory the main bottleneck, especially for inference. It’s not compute (even though per-die compute is stagnating, as we were saying), but it doesn’t matter because memory is a far larger bottleneck.

The speed of the guy in the back is what defines how fast our workloads go.

In practice, this means the amount of memory per chip, measured in gigabytes and soon, Terabytes, is exploding, going from 40 GB in 2020 with NVIDIA’s A100 to 288GB with 2026 chips, and increasing to, get this, 1 Terabyte of memory per chip with the Rubin Ultra chip slated for 2027.

So, to summarise, AI software, or models, requires AI infrastructure to get bigger and to have more compute available, both of which, in their own ways, are making hardware a system game.

That is, in modern AI, systems matter more than chips. If there’s something to take away from all you’ve read until now, it’s that.

And once you get this, all you’re about to read next will fall into place very quickly. Prepare to become more of an expert on AI than most blue-chip analysts (I’m not exaggerating; most professionals in this industry don’t understand most of what we are about to cover).

The Hardware Battle

To fully understand this “war” between the US and China, we need to look at three things: software (comparisons between AI models), hardware (comparisons between AI systems), and, perhaps most importantly, supply chain and geopolitical concerns.

Today, we are focusing on the latter two, so that I can show you how wrong most Western analysts are about China.

The entire thesis sits around two notions: systems matter more than chips, and China doesn’t care about profits. Stay with me.

To drive this home, we will compare what each bloc offers directly, side-by-side, and draw conclusions from that. Starting off, even though I’ve told you systems are what matter, in the comparison with China, we also need to compare single-chip performance, because that will help us understand China’s decisions.

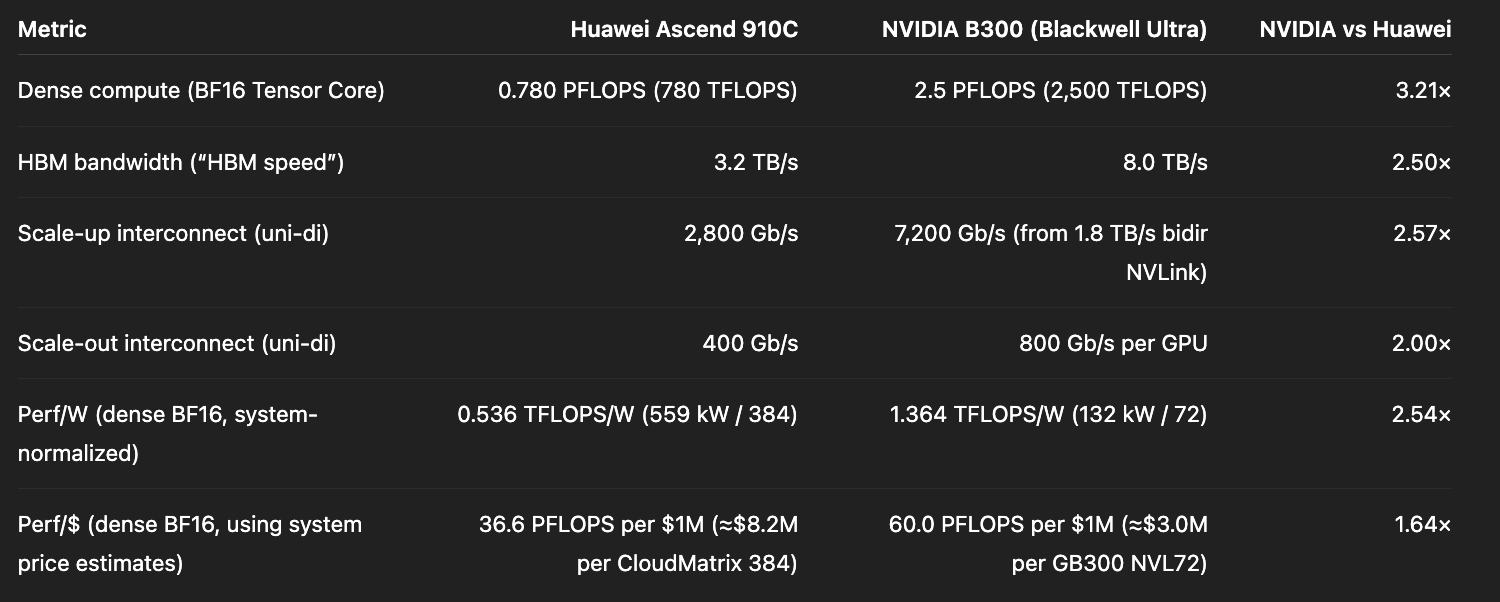

Below is a direct, single-chip comparison of the US and China’s most powerful chips currently: the NVIDIA Blackwell B300 and the Ascend 910C.

Source: Author

As you can see, NVIDIA seems to be ahead in all fronts, literally everywhere, both in terms of raw performance (compute and memory) and also efficiency (performance as a fraction of both power and dollars).

It’s literally night and day!

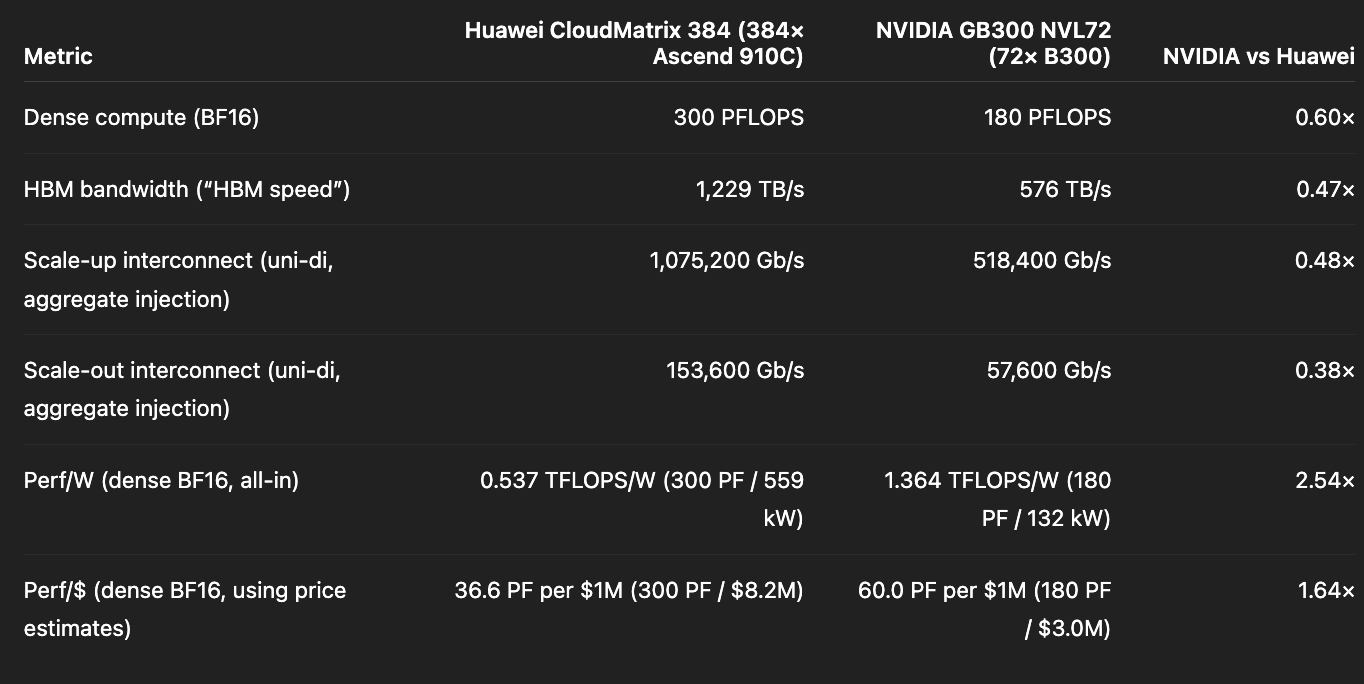

But let’s compare servers now. Instead of comparing single-chip solutions, we are now going to compare the top AI servers from China and the US: the Huawei CloudMatrix and the NVIDIA Blackwell Ultra.

As Hemingway wrote once, “gradually, then suddenly,” and just a few lines later, the tables have turned, we have completely reversed the framing of who’s ahead in terms of nominal throughput.

When scaling up, it appears that China is ahead.

And let’s take it a step further into the future and compare 2026 and beyond at the server level, now including both Huawei’s and NVIDIA’s upcoming servers based on the new Ascend 950DT and Rubin chips slated for 2026 and 2027, even though some metrics are still unknown, paradoxically to the companies themselves.

US/China server comparison throughout 2027. [e] stands for ‘estimate’.

It’s also important to mention that, with the Rubin GPU generations, NVIDIA is changing ‘what things mean’. The 144 and 576 numbers in the server names represent the number of GPU chiplets, with each now considered a ‘GPU’. In the case of the latter, we have 4 GPUs per compute tray and 144 trays, for a total of 576 GPUs.

To be clear, this is not how GPUs are counted in Blackwell, where a GPU is in fact 2 GPU chiplets in one package (otherwise, the Blackwell Ultra would be GB300 NVL144, because it has 72 trays with 2 compute dies each). If you’re confused, you’re not alone; this is famously known as “Jensen Math”.

At this point, it’s clear: on a nominal basis, without accounting for efficiency, China is racing past the West by sacrificing efficiency in lieu of outsized global performance.

Analysts who claim China is behind aren’t seeing the big picture and fooling themselves through the lens of their Western biases.

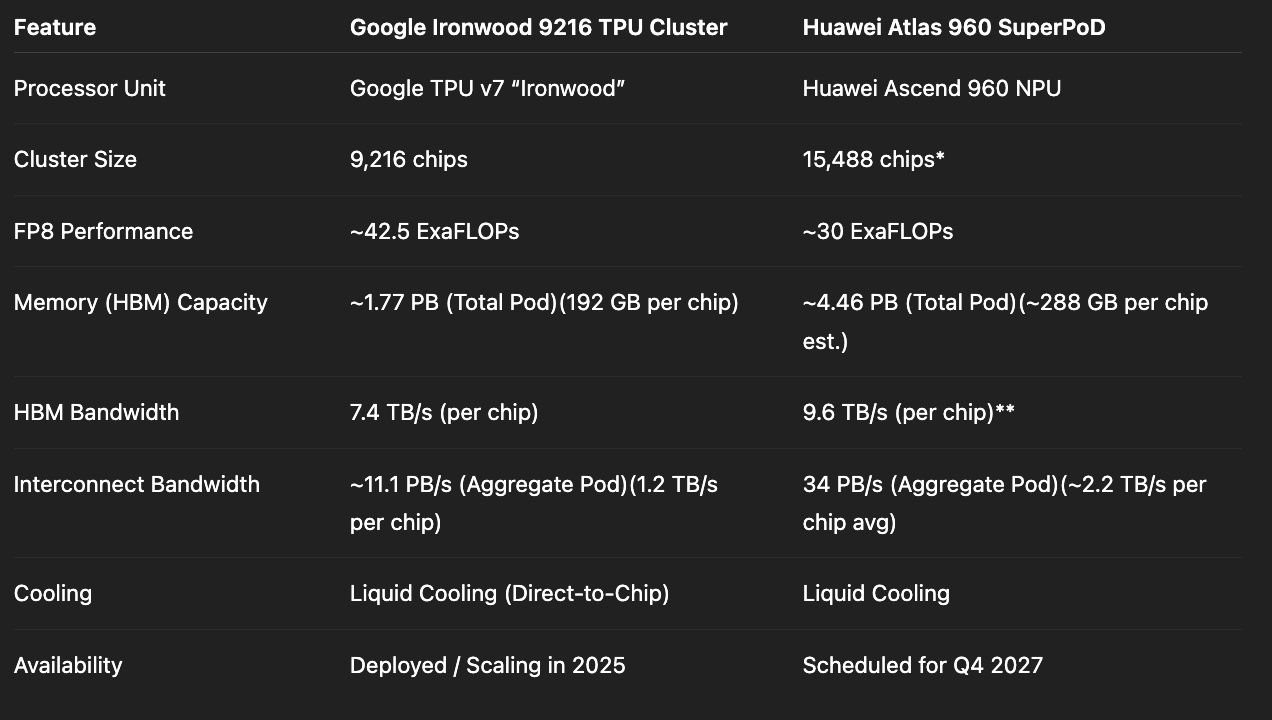

The silver lining for the West here is Google, whose Ironwood pod, released this year, is highly competitive even with Huawei’s Atlas 960 SuperPoD slated for 2027, ahead in terms of compute and behind in terms of memory simply because each NPU has more HBM memory (288 GB) than each Ironwood TPU (192GB). However, that’s not an engineering advantage; it’s just putting more memory into each chip.

Leaving efficiency to bear, by all accounts, Huawei is ahead of NVIDIA. But wait, efficiency matters, right?

We need to make our deployments efficient to make money from them. It’s all that we care about in the West! However, that’s your Western bias doing the talking, because here’s the thing:

China doesn’t care about profits.

This is the overarching conclusion I want everyone to digest here: China isn’t treating AI as a technology to make money right now; it’s a national security technology, where profits take a back seat to national interests and thus, can come later (if ever).

Yes, Huawei’s servers aren’t close to being remotely marketable, seeing NVIDIA and other US options, especially in the power-constrained West, but China. doesn’t. care. They will subsidize the use of domestic chips as long as they need to to advance their domestic chip efforts.

That’s why they are still increasingly pushing for local adoption of Chinese chips over NVIDIA's, offering huge subsidies in return and absorbing the losses for their AI Labs. That’s why China wasn’t desperate for lighter export controls even after the US lifted the ban on selling NVIDIA H200s to China (more on this later). The commitment to having a strong internal chip design and manufacturing is unwavering. This is best summarised by Chinese semiconductor analyst Poe Zhao after the US unlocked purchases of H200 to Chinese Labs:

“China will buy H200. China will use H200. But China won't bet its AI future on H200.”

But what China does care about, and where things start to get really interesting, is feasibility, because wanting is not the same as being able to.

The Supply Chain Battle

I’m a staunch believer, and so should be most “experts”, that the US’s competitive moat is not software. It’s not hardware specs either, as we have just seen.

It’s compute, or the ability to actually deploy it.

But if you had to pinpoint what the US’s biggest advantage is, what would you have said?

The Great American Advantage

According to a Bernstein Research report sent to Wall Street analysts, the US and allies have deployed 25 zettaFLOPs of compute in 2025, while China has deployed only <1 of Chinese chip ZettaFLOPs.

How “a lot” is that? Well, a lot.

I’m usually wary of such claims, but at least on the US side, the math more or less checks out. If we take Jensen Huang’s claim that they sold “4.5 million chips in 2025”, if we assume 80% of those were B200 equivalents and 20% H200 equivalents, that is:

3.6 million B200s, each with 5 PFLOPs of sparse peak power, give 18×1021, or 18 ZetaFLOPs

0.9 million H200s, each with 1781×1018, or 1.78×1021 FLOPs, or ~1.8 ZettaFLOPs

So, just NVIDIA alone, which primarily sells in the US due to export restrictions, we have around 20 ZettaFLOPs. Once we count AMD, Google, and Amazon ASICs, the 25 number feels very likely.

For the Chinese number, they expect ~1.5 million Ascend 910B equivalents to be produced in 2025, each with 0.4 PFLOPs, yielding a 0.6 ZettaFLOP total.

That’s almost a 50x difference, which is equally striking and revealing of where the US moat really stands.

China is ramping up heavily in 2026, as we’ll see later, which might put into question whether the US did the correct thing in unlocking the H200 for purchase.

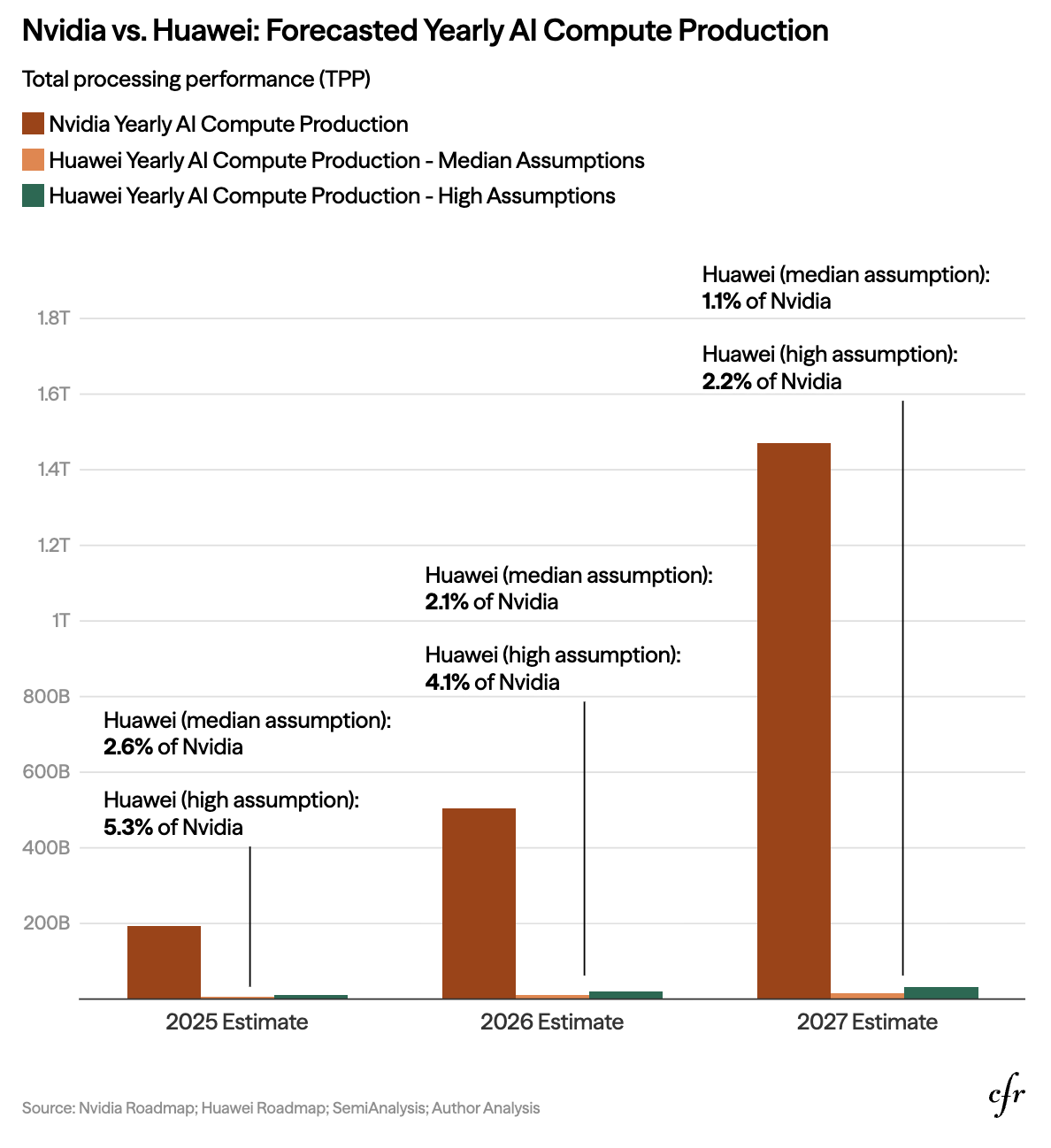

Alternatively, we can view this comparison using the US Government’s TPP metric, Total Processing Performance, which it uses to define which chips can be shipped to China.

It’s a precision-normalized way of comparing different chips based on peak compute capacity, and it shows how the United States is currently much more capable of deploying compute, and will be so for the next several years (the difference is actually increasing):

But even then, our Western biases fool us once again while trying to understand China, as, according to Reuters, despite the obvious compute deployment issues, China will still “recommend” that local purchasers make a proportional purchase of domestic chips to their NVIDIA purchases.

They don’t seem to mind starving on compute for a while if that means building a competitive chip manufacturing and packaging industry.

You realize, my dear reader, that this is not your average Western foe?

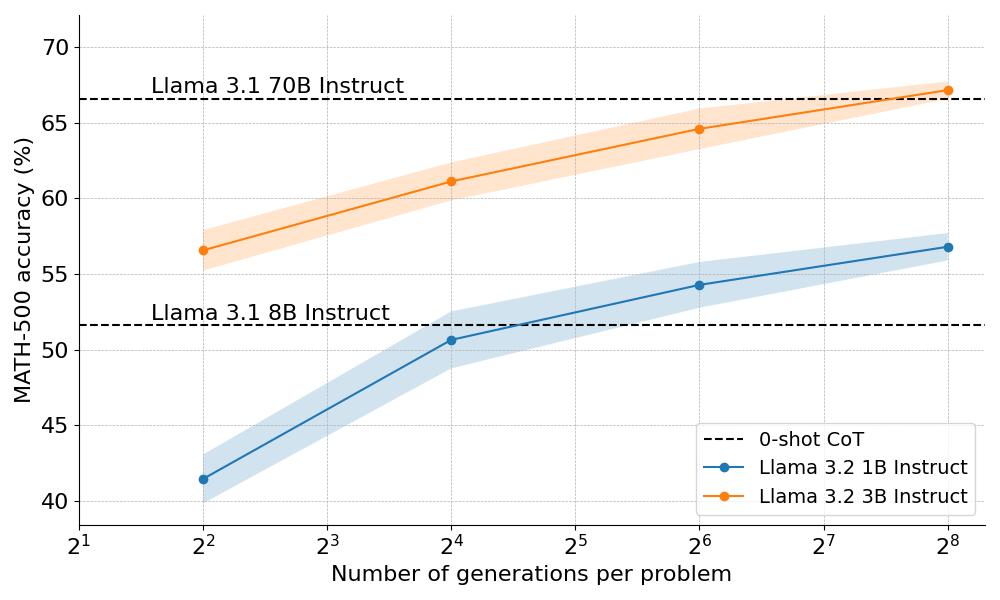

Having compute is not only necessary to train increasingly more powerful models (the first scaling law), but it’s also instrumental for inference-time compute (the second scaling law) or for deploying more compute per task.

Bigger models trained for longer are a strong predictor of better performance, but so is the capacity to deploy them for longer, which might be a stronger predictor of performance today.

As you can see below, you can make a smaller model’s performance become “as good” as a much larger model simply by allocating more compute:

Source: HuggingFace

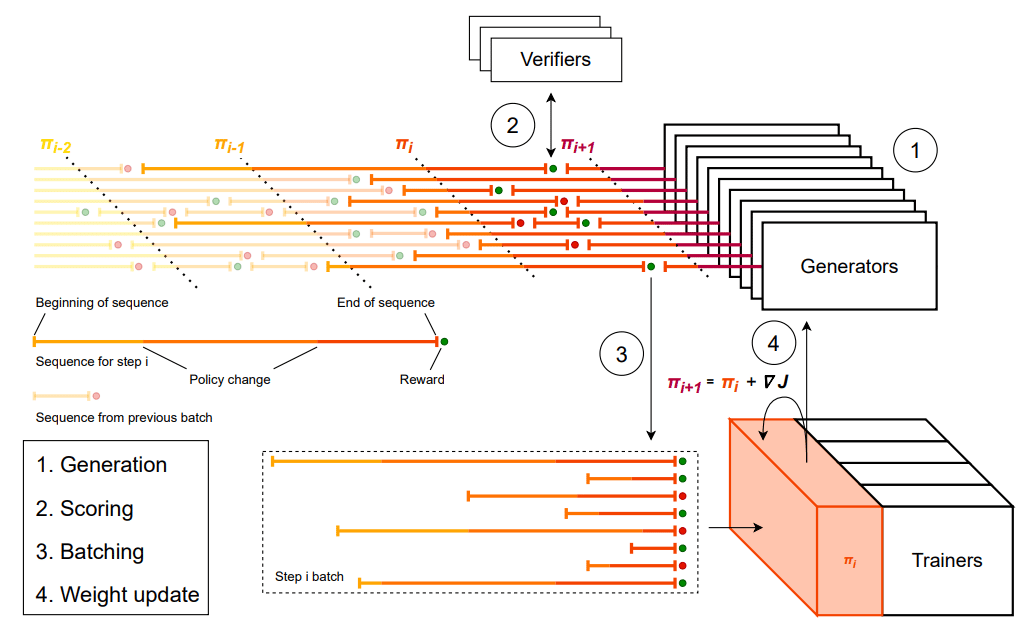

But as we said earlier, inference is now also critical to training, thanks to Reinforcement Learning. In such training, to update a model, to make it better, you take your current model version, generate, say, 100 inference rollouts (tries at solving the problem), see which ones worked, and learn from those (updating the model to a new state), and discard the rest.

Source: Mistral

But inference, no matter where you look at it, is a real problem to serve. Real demand is extremely latency-sensitive, which forces you, as an AI cloud provider, to preallocate compute resources to models that may be demanded in the future… or not.

So, in a scenario of already-tight compute, you’re also purposely risking having idle clusters waiting for sub-par demand simply because you need to meet SLA (Service Level Agreements) for users requesting access to those models.

As Alibaba acknowledged, at one point, they were using almost 20% of their compute capacity to serve only 1.35% of the total request volume. Inference is a nightmare that only gets darker when you’re compute-constrained like China. Hold this thought because this will become key later.

The reason inference is so painful to serve is that you need to have models preloaded into GPU memory, as performing ‘on-demand’ loading is prohibitively slow.

For example, a large model like Kimi K2, weighing at 2 Terabytes at BF16 precision, over a PCIe 4.0 connection from “fast storage” (storing models in storage, not in memory) with 32 GB/s speed would take 62 seconds the user would have to wait just for loading. And we aren’t even accounting for profiling steps, KV-cache setup/pinning, allocator state, etc.

Therefore, you have three axes of pressure to have more compute:

You need more compute to perform more ambitious training

You need more compute to deploy more inference-time compute to users and thus give better user experiences

You need more compute as you are purposely undermining your own utilization to meet SLAs

Today, AI is a ‘I need more compute’ game.

And knowing all this, what to expect in 2026?

What to Watch Out For in 2026.

The Secret is Scaling, but can they?

The moment you start to pull the strings to see where the different components of a Huawei CloudMatrix come from, you begin to realize where China’s real problems are.

To this day, China still relies heavily on the US and its allies for access to hardware and for the deployment of compute.

This server is a 599kW (more than half a MegaWatt) beast that takes an entire corridor of an AI data center, encompassing 16 racks, of which 12 are filled with NPUs (Neural Processing Units, a lower-power accelerator), with 32 per rack, and four racks for the networking gear required to make the accelerators communicate with each other.

As we saw earlier, this server is mighty. However, the issue for China is that most parts are foreign.

The chips, the Ascend 910C, China’s most powerful chip, were designed in China but, to this day, are still primarily based on an illegal purchase of manufactured and packaged chips from TSMC, not produced locally (though this is changing, as we’ll see in a second).

TSMC was allegedly fined $2 billion for this, clearly ignoring the US ban that prohibits Taiwan’s TSMC to manufacture chips for Chinese companies.

The memory chips are also foreign, coming from a huge purchase made by Samsung last year, before the HBM sanctions kicked in (memory chip companies are also forbidden to manufacture for Chinese companies).

And perhaps even more concerning for China, the advanced packaging was also performed by TSMC, the process that packs the compute Ascend dies and the Samsung HBM chips into a single CoWoS (Chip-on-Wafer-on-Substrate) package, one of the industry's key bottlenecks.

But this could soon meaningfully change. As soon as next year, actually.

The Great Ramp-Up

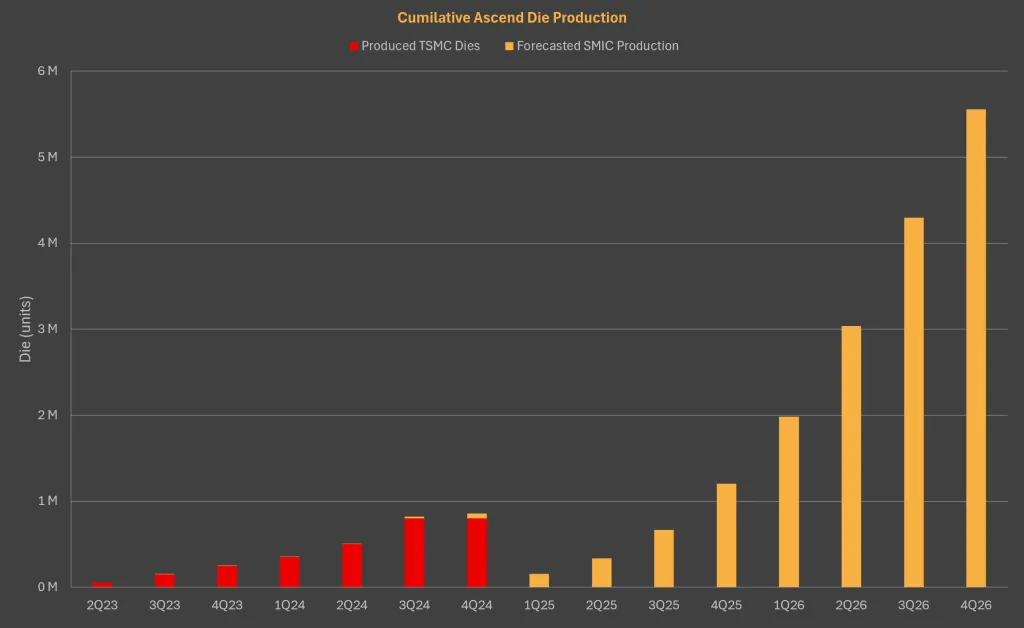

China’s current most significant manufacturing and advanced packaging champion, SMIC, has considerably ramped up manufacturing capacity for 2026, to the point that SemiAnalysis believes SMIC, once a bottleneck to Ascend chip production, will no longer be one, meaning 2026 could see a considerable increase in locally-produced Ascend chip dies to more than 3.5 million dies in 2026 with SMIC alone.

Source: SemiAnalysis

On the other hand, Huawei, once just a chip designer, seems very committed to becoming a fully verticalized company, from wafer fab equipment to chip design to advanced packaging (including proprietary HBM). In other words, Huawei is primed to become ASML, NVIDIA, and TSMC all in one.

But how?

Subscribe to Full Premium package to read the rest.

Become a paying subscriber of Full Premium package to get access to this post and other subscriber-only content.

UpgradeA subscription gets you:

- NO ADS

- An additional insights email on Tuesdays

- Gain access to TheWhiteBox's knowledge base to access four times more content than the free version on markets, cutting-edge research, company deep dives, AI engineering tips, & more