THEWHITEBOX

TLDR;

Welcome back! This week, we take a look at a lot of market data, including both Taiwan and the recent Venezuelan lore. We also discuss new algorithmic improvements coming out of China in great detail, billion-dollar acquisitions, the ‘eternal’ Tesla vs Waymo debate, and how a small AI startup is kicking the ass of large AI Labs.

Enjoy!

Earn a master's in AI for under $2,500

AI skills are no longer optional—they’re essential for staying competitive in today’s workforce. Now you can earn a fully accredited Master of Science in Artificial Intelligence from the Udacity Institute of AI and Technology, awarded by Woolf, an accredited higher education institution.

This 100% online, flexible program is designed for working professionals and can be completed for under $5,000. You’ll build deep, practical expertise in modern AI, machine learning, generative models, and production deployment through real-world projects that demonstrate job-ready skills.

Learn on your schedule, apply what you build immediately, and graduate with a credential that signals serious AI capability. This is one of the most accessible ways to earn a graduate-level AI degree and accelerate your career.

IPOs

The Revealing (and Concerning) Truth about China’s AI Lab Financial Struggles

In December 2025, Zhipu AI and MiniMax filed Hong Kong IPO prospectuses days apart (hearings Dec 16–17; prospectuses Dec 19–21), with filings highlighting fast growth but faster cash burn. In other words, these companies are in quite a bit of trouble and losing tons of money (dollar conversions below use $1 ≈ ¥7.0367).

At first, the numbers look like heaven on Earth.

Zhipu's revenue rose from ¥57 million (~$8.1 million) in 2022 to ¥312 million (~$44.3 million) in 2024, a 447% increase.

MiniMax reported $30.5 million in revenue in 2024 (up 782%) and $53.4 million in the first nine months of 2025.

These guys are printing money, or so you would think. Moreover, gross margins, how much they charge per token relative to the costs of producing that token, were also decent: Zhipu 56% (2024); MiniMax B2B 69.4% (first three quarters of 2025). This means Zhipu charged per token 2.27 times the cost of producing that token, while Minimax, being more enterprise-focused, charged 3.3 times the cost.

Strong pricing power. In principle, this signals a healthy business; one that is offering something at a price well above the costs of producing it.

But then, why are these companies hemorrhaging money?

The problems start when you factor in the cost of maintaining that pricing power. In AI, you can sell tokens as long as your model is on the frontier of what your customers can access. Otherwise, customers churn on the spot.

Yes, companies like OpenAI have that brand value, or brand moat, that makes them a choice by default even if their models aren’t necessarily the best, but that is not the case for the rest of the world.

And the costs of creating these models are eating companies alive on both sides of the Pacific, making the overall losses much larger than revenues.

Zhipu adjusted net loss grew from ¥97 million (~$13.8 million) (2022) to ¥2.47 billion (~$351.0 million) (2024).

MiniMax losses rose from $7.37 million (2022) to $465 million (2024).

As you may have guessed, spend concentrated in R&D/compute. Zhipu R&D hit ¥2.2 billion (~$312.6 million) in 2024 (vs ¥84 million, or ~$11.9 million, in 2022). Of these, ¥1.55 billion (~$220.3 million) went for compute services (about 70% of R&D), with marketing also having a strong presence of ¥387M (~$55.0M) in 2024.

Not only is the product expensive to improve, but it is also effectively commoditized, meaning you also have to spend a lot on marketing to differentiate it.

MiniMax, on the other hand, reported $142 million in training-related cloud compute costs in the first nine months of 2025, with training cost as a share of revenue improving from 1,365% (2023) to 266% (first three quarters of 2025).

I believe this dramatic decrease in training costs relative to revenue is a combination of both the company selling more (training doesn’t sell, that’s inference), and also deploying cheaper, distilled models to users.

But when cash pressures become particularly dramatic is when you factor in the actual addressable market. Against a cited China LLM market size of ¥5.3 billion (~$753.2 million) in 2024 (¥4.7 billion (~$667.9 million) enterprise; ¥0.6 billion (~$85.3 million) consumer), the two firms’ combined burn (~¥27.6 billion/year, or $3.92 billion/year) is multiple times total current market revenue.

In short, what appeared like a great business is turning out to be a money drain.

TheWhiteBox’s takeaway:

The situation is probably “as bad” in the US, but access to capital is much greater there than in China. Therefore, my takeaways are three:

China doesn’t have a magic pill that makes the entire business case pan out. Its labs are suffering the cost of progress just as much as their US counterparts.

The Chinese venture capital ecosystem isn’t as deep as the US one, leading Chinese Labs to having to IPO to access liquidity.

I’m genuinely surprised by the CCP’s inaction toward these obvious liquidity concerns, especially for Zhipu, which is known to have state-level support.

To me, this shows how misunderstood the CCP’s role is in the West. We always portray the CCP as this overarching, all-encompassing entity in control of everything.

And while that thought does hold merit (the CCP has total power to intervene in any business at pleasure), they mostly avoid doing so when the industry is as dynamic as AI software, and will instead let the winner be decided based on simple laws of market and demand, extreme capitalism, even if that means seeing Labs perishing in the effort.

Don’t get me wrong, they do have favorites like DeepSeek or Unitree, but it’s not like they are subsidizing the entire industry, especially in software. This might also suggest they don’t view AI software as a moat and instead want to focus on developing their national semiconductor supply chain.

And talking about China…

GEOPOLITICS

Will The Taiwan Question be Answered in 2026?

Xi Jinping’s New Year address showed, once again, how committed the People’s Republic of China, and in particular its current leader, is to the One China policy; reunifying Taiwan, the Republic of China, under Chinese rule.

“The reunification of Taiwan is unstoppable,” is what the Chinese leader said.

I don’t think I have to tell you how bad this would be for AI if China decides to invade. Even if they just block the Taiwan Strait and prevent chips and packaged accelerators from leaving the island. That thing alone would be enough to crash the entire industry with an unfathomable force (and with AI, the rest of the economy).

It’s important to note that the world is not prepared for such an event in the slightest. On this topic, I get asked a lot, “What about the TSMC fab in Arizona?” But as I explained on Sunday, the Arizona Fab is a chip-manufacturing fab, not an advanced packaging one.

This is a very important misconception that leads many people to hold false beliefs about the US's current dependence on China. When people talk about ‘producing GPUs’ or TPUs, they knowingly or unknowingly refer to two steps:

Manufacturing the chip, which I explained in more detail in the Technology section above,

Packaging the chip into a single system-on-package that includes not only the manufactured compute dies, but also the memory chips shipped from SK Hynix or Samsung.

Historically, packaging was considered a less important part of the process, serving only physical protection and heat dissipation. However, as we approach the limits of Moore’s Law (our ability to pack more transistors onto a single chip), limiting how much performance we can get from a single compute chip, we have resorted to packaging several chips into a single package to behave as “one,” making it not only necessary, but an absolutely crucial and complicated part of the process and the primary driver of progress.

Therefore, when we talk about ‘GPUs’, we are actually referring to a complete package that includes, in the case of NVIDIA Blackwell, two compute dies stitched together, and 8 HBM stacks connected to these compute dies via a silicon interposer.

And the reason I’m telling you this is that the packaging is still made in Taiwan, even though the chips are manufactured in the US. That is, the compute dies are built in Arizona, but they are then shipped to Taiwan for packaging.

In other words, NVIDIA products, as so are AMD’s or Google’s (and Apple’s) are still totally geographically dependent on Taiwan.

Additionally, Taiwan has the “N-2” rule, which prevents the manufacture and packaging of chips that are less than two generations away from the frontier. That is, if Taiwan starts manufacturing 2nm process-node chips, the Taiwanese government would not allow TSMC to open fabs elsewhere to produce those chips (or 3nm). That is why the Arizona fab is a 4nm process node, as Taiwan is nearing production of 2nm chips.

Arizona will open its first 4nm advanced packaging lab in 2027, part of a partnership between TSCM and US-based Amkor.

TheWhiteBox’s takeaway:

It’s only January 4th and just from Xi Jinping’s speech coupled with the US actions in Venezuela, seizing the largest oil reserves on the planet (~18% of known global reserves), one of China's key suppliers, we can already predict 2026 is going to be a messy year geopolitically.

How these actions could affect the Taiwan conflict is unknown, but rest assured, China is not happy. The Pentagon still believes no invasion will occur before 2027, but I wouldn’t be surprised if China becomes much more aggressive in 2026 and even considers probing naval blockades.

That said, I’ll talk more about this in my predictions for 2026, but I believe that, black swans like this aside, 2026 should be a good year for markets if geopolitics don’t screw us all over.

One way or another, I predict this newsletter will have to take geopolitics much more seriously this year.

THEWHITEBOX

Eye on the Market

TheWhiteBox appearing as a source in the report

As I mentioned in a previous post, I’ve been working with JP Morgan Asset Management (AM) over the last few weeks, advising on a report that came out yesterday: Eye on the Market, by Michael Cembalest, Chief Investment Officer at JP Morgan AM.

Specifically, I advised him and this team on the sections ‘China scales the moat’ and ‘A Metaverse moment for hyperscalers’, on various aspects like getting the opaque and complex world of “semis” numbers correct, and some key takeaways like the importance of systems over chips (something I’ve been telling you from this newsletter for years now).

I hope that, if I did my job, many of the key conclusions in those sections are reminiscent of things I’ve told you in this newsletter before.

Beyond the sections I participated in, the report is truly worth the read, especially the sections on energy, one of Michael’s strong points, and very illustrative of another point I’ve made before in this newsletter: energy is a very significant constraint in AI.

You can download the report for free, which is well worth reading, here.

AGENTS

Meta acquires Manus for ~$2 billion

Manus, an agent-harnessing company (AI startups that build ‘agent scaffolds’ around third-party models, like Cognition), announced on December 29 that it is joining Meta, framing the move as validation of its work on “general AI agents” intended to help with research, automation, and complex tasks.

TheWhiteBox’s takeaway:

I was shocked by this announcement, considering the ties between Manus, a Singaporean company, and China. What I’m not surprised about is Zuck’s steadfast commitment to play a role in the future of AI, even if it’s mostly by purchasing its way into the table.

2026 should be the year where we see whether Meta’s strategy, especially with the formation of their SuperIntelligence Lab, built via poaching superstar researchers from other top Labs, pans out. People love to bet against Zuck only to get burned, and I personally think this time won’t be different.

Meta’s “return” or not is also one of the crucial questions to be answered in 2026. In particular, one of the biggest questions is how AI will be blended into ads.

We have seen some pretty remarkable proposals recently, like xAI wanting to modify films and series by literally embedding ads into the picture using in-painting. However, I still believe the most likely outcome is to use LLMs to decide what to show users, serving as the decision layer for which ads to show customers.

I’ve already expressed extreme skepticism about the economic feasibility of all this, but given the lackluster revenue performance from AI Labs and Hyperscalers, I don’t see another choice.

JOBS

2026, the year of AI coming to labor?

A growing number of enterprise investors say 2026 is likely to be the year AI shifts from boosting productivity to directly replacing some work, accelerating pressure on hiring and headcount.

This TechCrunch piece points to research suggesting a meaningful share of jobs are already automatable with today’s AI, alongside employer signals that entry-level roles and some layoffs are increasingly being attributed to automation.

In a survey of enterprise-focused VCs, several predicted budgets will increasingly move from labor to AI spend. Hustle Fund’s Eric Bahn framed 2026 as an inflection point, with open questions about whether automation will first concentrate in repetitive roles or expand into more complex, logic-heavy work.

Other investors were more direct: Exceptional Capital’s Marell Evans anticipated labor cuts alongside bigger AI budgets, while Battery Ventures’ Jason Mendel argued “agents” will push software beyond helping workers to automating the work itself in certain areas.

Black Operator Ventures’ Antonia Dean added a cautionary note: even when AI isn’t the true driver, executives may increasingly cite it to justify workforce reductions, making “AI did it” a convenient scapegoat narrative as enterprises restructure.

But is this happening for real?

TheWhiteBox’s takeaway:

Considering the survey was done on VCs, what did TechCrunch expect they would say? Besides pointing out the obvious, to me, deciding whether this is just wishful thinking or sound predictions will depend mainly on two things: RLaaS and non-determinism.

The former refers to the idea that enterprise AI will only work once we start training models on the job’s data instead of just doing prompt engineering.

Without that on-the-job knowledge, it will be tough for agents not to make mistakes, which may erode the entire point of using AI in the first place. Monitoring the adoption of tools like Thinking Machines Labs’ Tinker API, which facilitates model fine-tuning for companies, will be crucial to determine whether RLaaS truly becomes a thing.

As for the latter, non-determinism, or the unpredictability of AI workloads, will remain an important issue, especially given the still-concerningly high hallucination rates some of these models exhibit.

Benchmarks aside, I find that GPT-5.2 Thinking models rarely hallucinate, but Gemini 3 models do so a lot in my experience, even prompting me (pun intended) to downgrade my subscription from Ultra to Pro.

Solving “non-determinism” or running models in a way that we know what the result will be in advance not only reduces some hallucinations meaningfully (the mistake comes not because of random sampling, but because the model literally predicts a wrong response), but also allows enterprises to write appropriate tests and evaluations to assess workload readiness confidently.

Put simply, if we can predict outcomes, we can evaluate model responses, pre-identify mistakes, and correct them via fine-tuning or better prompting.

Careful, eliminating hallucinations is in itself nonsensical because, in a way, all these models do is hallucinate. Instead, what people refer to as ‘hallucinations’ is actually factual mistakes, which can be largely solved with full determinism.

Overall, until these two things are solved, adoption claims are based on nothing but “projections of desire VCs have”, and I would be very wary of making adoption claims for automation purposes as long as both persist.

In fact, the only places where AI has made real progress, like coding, are creative areas and iterative work where hallucinations are tolerated; the point of discussion here is whether probabilistic AIs can play a role in automation.

THEWHITEBOX

Poetiq Achieves Remarkable Result

The team at Poetiq has achieved a pretty remarkable result on the ARC-AGI 2 benchmark, beating all other competitors, including top AI Labs.

This benchmark is widely considered the hardest AI benchmark today, in which AIs must solve complex puzzles using just a handful of examples to find the pattern (usually around three). You can try a puzzle for yourself here.

The idea is to define a memorization-resistant benchmark that prevents models from memorizing their way out of solutions (retrieving solutions from memory rather than actually reasoning them).

While most models at the top of the benchmark ranks are the AI Labs themselves running models on their own hardware (or simply by brute force), one company running its own “agent pipeline” on top of its models has managed to beat them all.

Impressively, they manage to beat OpenAI’s own score with GPT-5.2 (x-High) by almost 20% despite requiring only a few dollars more per task. This is literally outsmarting OpenAI with their own models.

But how have they done it?

More specifically, Poetiq’s “harness” is an orchestration layer around a base LLM that turns solving an ARC-AGI task into an iterative, testable loop rather than a single prompt-and-answer.

In other words, it’s a system that helps models “think better.”

The model proposes a rule for the puzzle, often expressed as executable code; the harness runs it on the provided training input-output pairs, and then feeds back the exact mismatches so the model can revise the rule/code and try again. This repeats until the candidate matches the training examples well enough to apply to the test grid.

Two practical features matter:

It self-audits progress and stops when further iterations look unhelpful (to control cost),

And it’s model-agnostic, meaning it can swap models or assign different models/attempts to different roles (hypothesis generation, coding, debugging, selection).

ARC Prize describes this general approach as a “refinement loop” system built on top of a frontier model, where the performance gains come from the loop and verification, not retraining the base model.

TheWhiteBox’s takeaway:

I’ve been very outspoken about my skepticism of agent-harness AI startups as viable companies, and I still believe so. In fact, I think the future that awaits them all is either death or being acquired, as has happened with Manus and Meta.

That said, they are a symptom of a larger trend: systems. AI Labs no longer release models; they release systems that include, as the decision-maker or logic, one or several models. This was even defined exactly this way by Gemini’s pre-training lead.

In my view, this exemplifies the limitations of AI models today, which require this “additional help” to think better. Ideally, all this additional harnessing should be eventually absorbed into the model (meaning the model itself should improve its predictions, not being helped at runtime).

Still, as of today, it remains vital to make models “useful.”

THEWHITEBOX

The First-Ever Coast-to-Coast Ride

A Tesla driver using FSD v14.2 has achieved the first-ever coast-to-coast ride while requiring exactly zero human interventions, meaning the driver did not intervene at any point during the 2 days and 20 hours ride across +2,700 miles (~4,300km).

This remarkable feat, not achieved by any other vehicle in history, is an essential milestone in our quest for truly autonomous driving, and it was even celebrated by the famous Andrej Karpathy, who once served as the Director of AI at Tesla.

TheWhiteBox’s takeaway:

Tesla’s data advantage must not be underestimated. Yes, Waymos have an undeniably higher level of autonomy today, mainly attributed to using extremely overfitted AI models that memorize entire cities to the dot in place of generality (you can’t deploy a Waymo in an unmapped town).

On the other hand, Tesla’s software is much more general, avoiding city layout overfitting but with worse edge-case handling. In other words, Waymos are better prepared for unexpected situations (as long as they occur within their accepted map), but Teslas can be deployed across the entire US.

Which approach is better? As we always insist, we don’t know yet.

Tesla has millions more cars deployed around the world gathering key data to improve their models time and time again, something Waymo simply can’t.

However, Waymo’s sensor fusion system, which combines LiDAR and cameras (not just cameras, as Tesla does), offers greater robustness in edge cases, making it a safer option when the two are available.

So the question is: can Teslas achieve the same level of edge-case handling as Waymos? If they do, the point of using Waymo’s approach disappears, as Teslas are cheaper and more general.

But as long as Teslas do not achieve the same level of autonomy, people will still prefer using Waymos, for obvious reasons.

SEMICONDUCTORS

The Most Advanced thing humanity has ever created

Have you ever wondered what the most impressive thing humanity has ever built is?

We’ve gotten to the moon, and we’re “approaching” making nuclear fusion viable by creating “artificial suns” on Earth. But, in my view, although I’m biased, none of these come close to the absolutely absurd and unfathomable technology behind EUV lithography machines created by ASML.

And Veritasium, a popular YouTube channel, has published a long-form video that, if you’re curious about how advanced chips are manufactured, is an absolute must-watch.

But what is an EUV lithography machine? These $400-million-a-pop machines are responsible for printing a logic circuit onto a silicon wafer. However, these circuits are so small that they can’t be manufactured using standard equipment.

Instead, they are printed using photons. That is, we use extreme ultraviolet light (light with extremely short wavelengths) to print the circuit into silicon, avoiding large diffraction angles to concentrate as much light as possible onto the reticle.

The process is a four-step loop. Once you have a Silicon wafer, where dozens or even hundreds of chips will be printed on, you:

Add a photoresist coat to the wafer, a material that is sensitive to light.

You send light through several mirrors and eventually through a retical ‘mask’ that has the desired circuit pattern. Once the light hits the photoresists, it makes those parts more soluble. We then provide a chemical bath that dissolves the impacted photoresist.

We ‘etch’ those parts and deposit copper on those “holes”.

We wash off the excess photoresist, giving us the first layer.

This process repeats dozens of times, adding layers to the chip (transistors are in the base layer; the rest is wiring).

If you watch the video, you will have to come to terms with one fact: how did this even get to work?

TheWhiteBox’s takeaway:

I don’t care what anyone says; after you watch the video, you’ll agree with me that humans have never developed something more complex than this. From creating small star explosions (supernovas) by hitting 50,000 tin plasma droplets per second using a laser, to numerical apertures and wavelengths, the science behind these machines is just otherworldly.

Just a fact to encourage you to watch the video. The mirrors that are used to focus the light and send it to the wafer are so smooth that, if they were the size of the Earth, the highest “bump” would be thinner than a poker playing card.

MODELS

A Small Frontier Model from China?

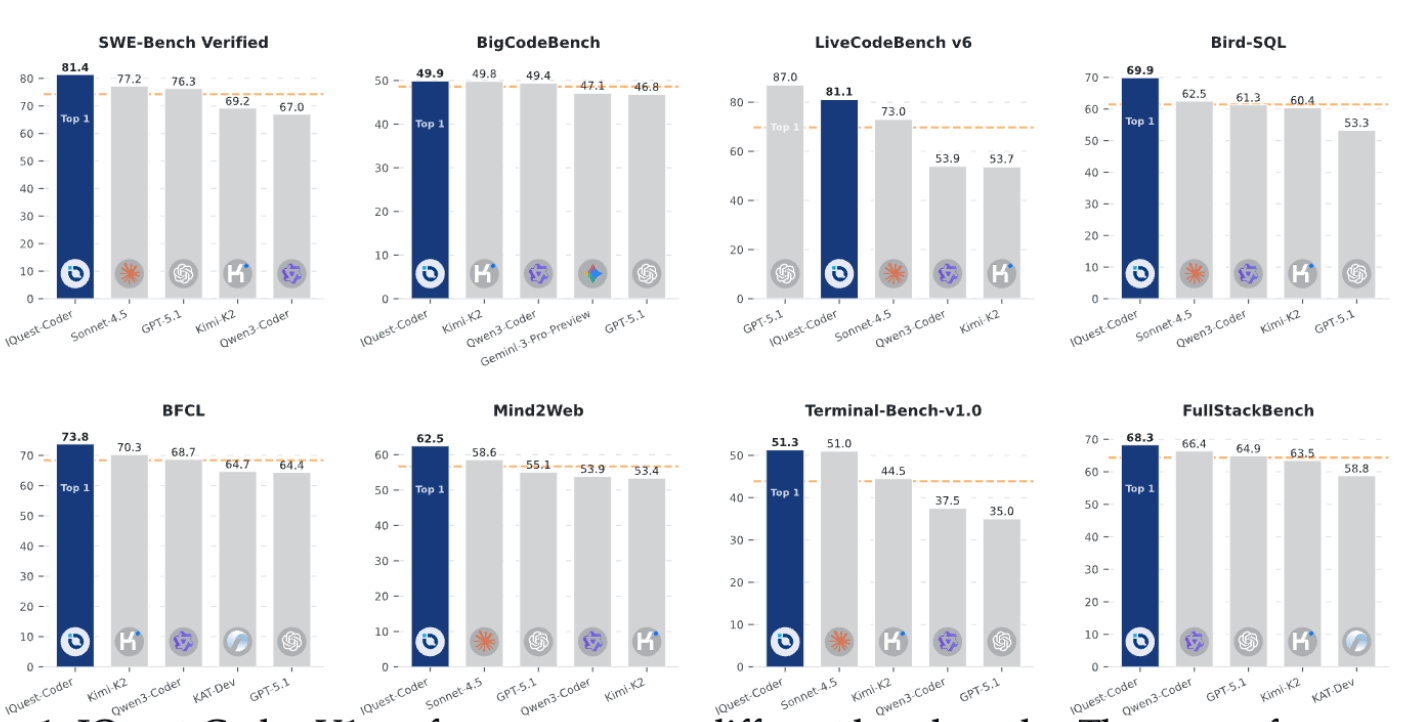

Another Chinese AI Lab has come out of the blue with quite the remarkable claim. With just 40 billion parameters, its new iQuest model offers almost frontier performance despite being orders of magnitude smaller than similar-scoring models. The alleged secret is the use of a looped Transformer architecture.

But what is that? Has China figured out a way to play the frontier game while requiring orders of magnitude less compute?

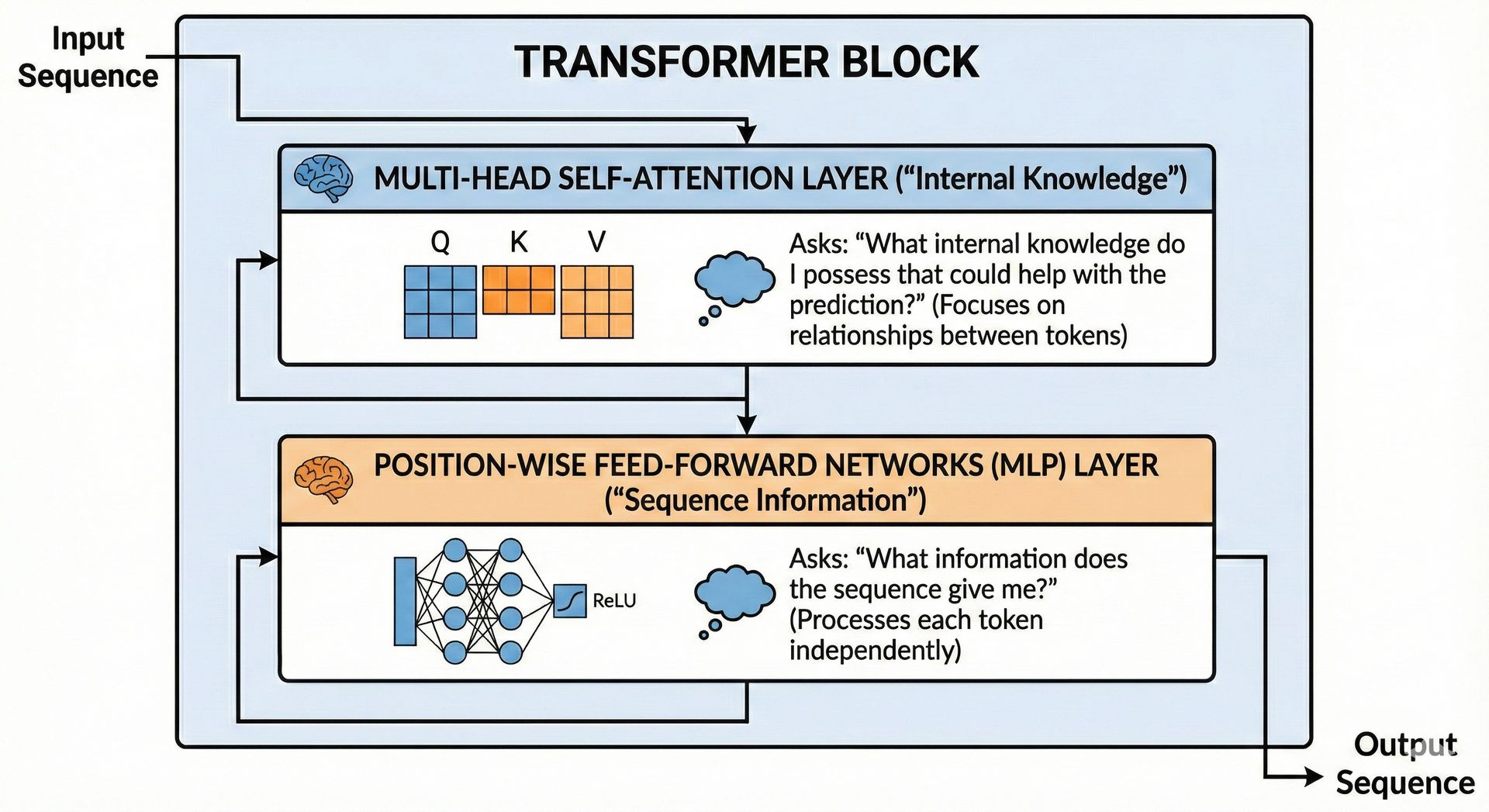

Current Large Language Models (LLMs) are all Transformers, a concatenation of what we know as ‘Transformer blocks’ as I’ve explained multiple times, more recently here. The way I best understand Transformer blocks is as a “knowledge-gathering exercise” that considers both the sequence and the model’s internal knowledge.

In other words, each block asks two “questions”:

“What information does the sequence give me?”, using attention layers,

“What internal knowledge do I possess that could help with the prediction?”, using MLP layers.

A representation for a single Transformer block and what each part does. Source: Author

This process isn’t enough with just one block, so we effectively concatenate dozens or even hundreds of these layers. After several iterations, we should have a model that, more or less, knows what the next prediction is.

A looped Transformer follows a similar pattern, but with an added twist. After we get the result of the last block, instead of going directly to make the prediction, we send that last output back into the first block and repeat the process.

Think of this as if you are about to make a prediction, but instead of opening your mouth with the answer, run one last thought effort to make sure you aren’t shitting the bed.

This is akin to giving the model “more time to think” but at the forward-pass level; instead of allowing more computation by letting models predict more tokens (as we usually do with inference-time compute), we let the model run more computations on every single prediction.

What a Transformer model looks like, in essence. Source: Author

The second loop is a little more complex than this, but it would make the explanation too long. The key takeaway is what I’ve described: finding a way to let models think internally for longer.

TheWhiteBox’s takeaway:

But besides the obvious explanation for “why”, this is more about fighting the computational constraints.

For a non-looped Transformer, the only way to increase forward-pass or single-prediction compute is to increase the model's depth. That is, the number of Transformer blocks. Consequently, that implies increasing the number of parameters, growing our model’s size.

Instead, this is about sticking to the same model size but doubling the compute effort by letting models “review their own thoughts” at least once.

We’ll talk about this more in detail in our predictions post.

Closing Thoughts

In the first days of 2026, everything, including AI, has taken a back seat to the US’s intervention in Venezuela. But the industry continues to make progress.

One of the early signs of change, something I’ll address more carefully in the 2026 predictions post, is that people are seriously reconsidering architecture alternatives to the standard Transformer, which remains too expensive.

So, will the Transformer be displaced? We’ll take that question in that predictions post, but what we can already say is that, to the despair of many enthusiasts, AI architecture is not yet “solved.”

Moreover, it’s pointless to refer to AI as ‘models’ and not ‘systems.’ The algorithm is just a part of a far more complex system of tools, runtime environments, databases, APIs, and other surrogate AI models like verifiers that make AI a much more sophisticated technology than it was just one year ago.

Finally, the other point worth mentioning is hardware, which will also see renewed importance in 2026 across several discussions: the ASIC trade, the growing importance of memory and optics hardware, and China's unwavering commitment to risk it all in the name of the One China policy.

And while I am going to try to predict 2026, as my predictions in 2025 came out pretty good, I can already attest that nobody really knows what is going to happen. Predictions and just that, guesses full of half-assed assumptions that, most of the time, are poorly assumed, particularly dramatic when making predictions about AI and semiconductors, the most fragile supply chains in the world.

Thus, whatever it may be, we already know 2026 will not be boring.

Give a Rating to Today's Newsletter

For business inquiries, reach me out at [email protected]