THEWHITEBOX

TLDR;

Welcome back! This week we have another week packed with insights and fresh news, from Gemini’s new deep research tool setting new records, OpenAI releasing GPT-5.2 literally seconds ago, the evolving drama around space GPUs, or the increasing supply shortage pressures in the memory chip market that could redefine AI in 2026.

At the end, we’ll also look at our portfolio, including a refreshing new look at one of the big stock winners so far in 2025 that could have an even better 2026, and a new aspect that most have missed: in AI agents, GPUs aren’t the bottleneck, meaning most people have AI hardware wrong.

Enjoy!

SPACE

Training Models in Space… Works?

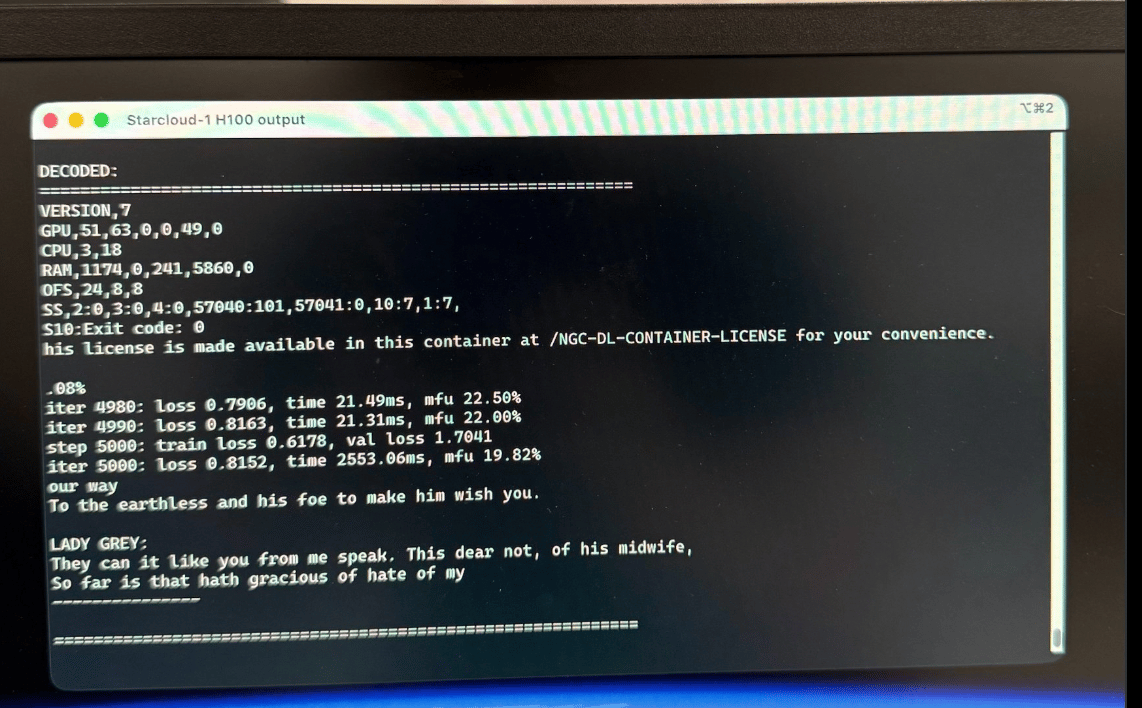

One of the hottest debates in AI today is whether space-based data centers make sense. Everything started after NVIDIA announced that a startup they had invested in, Starcloud, was sending an H100 GPU into space.

Many, including NASA engineers, have since said this would never work. Yet, not only is NVIDIA excited about it, but Sundar Pichai, Google’s CEO, literally can’t stop talking about it.

In the meantime, Starcloud, the startup NVIDIA supports, has announced its first training and inference runs. They trained nanoGPT, a minute Large Language Model (LLM) trained on the works of Shakespeare, and also managed to run inference of a Google Gemma model. Quite the success for a project that was never intended to work.

TheWhiteBox’s takeaway:

There’s far from being a consensus on this matter, and the debates are heated. For Starcloud, this is the only way: let results do the talking. Whether this is just pure desperation from Hyperscalers running into power constraints on Earth or really a genius idea, time will tell (I honestly have no idea, I’m not a rocket scientist).

What I will say is that the debate is artificially created. We are artificially constraining power supply in the West due to restrictions on nuclear and solar power, two technologies that could scale to our needs (the former is essentially unlimited power, the latter has the shortest lead times among all power technologies).

And talking about power…

THEWHITEBOX

From Supersonic engines to Data Centers

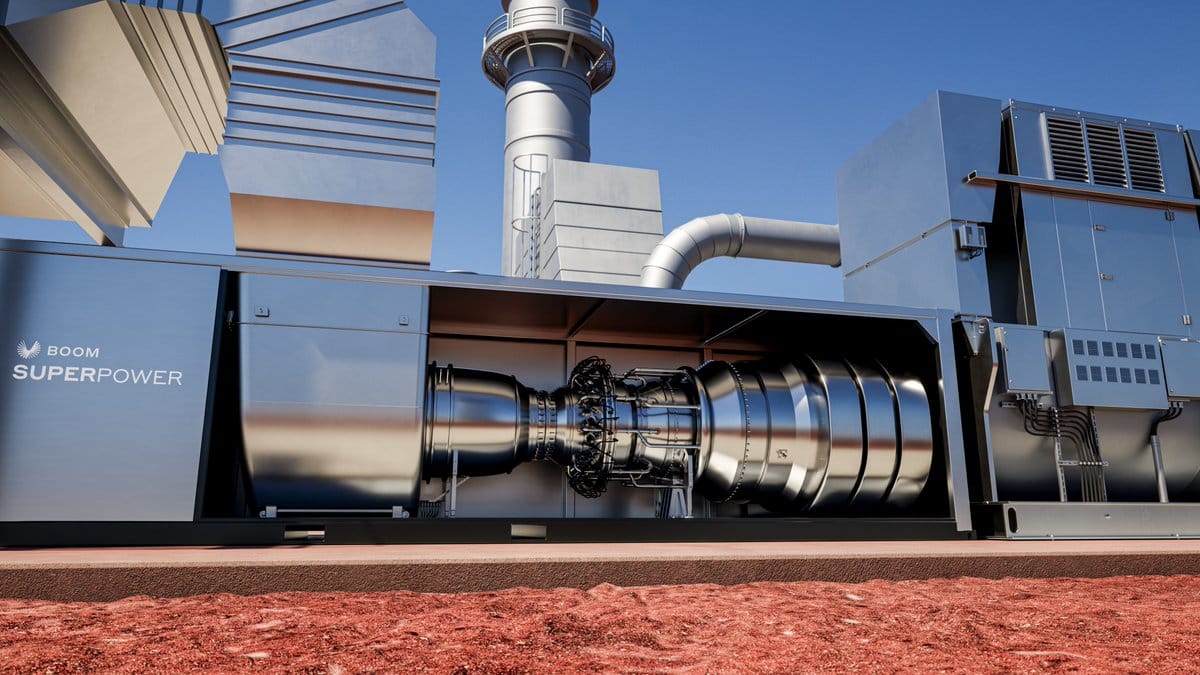

One of the coolest recent stories is a supersonic jet company repurposing to build data center turbines. As the CEO explains in this post, it’s quite the story.

They initially aimed to deliver the supersonic product first (a jet that is faster than the speed of sound) and then the energy product (using the turbines for power generation). But as they saw the emerging importance of power in the US, they shifted and have since landed a 1.2 GW contract with Crusoe (one of the primary data center builders for OpenAI), based on their 42 MW turbines for a total value of $1.25 billion, which nets at around $1 billion/GW.

This has allowed them to land $300 million in new financing, a story that explains how it’s always about building something people want.

But why is this a big deal?

TheWhiteBox’s takeaway:

You probably know by now that one of AI’s biggest bottlenecks is energy; we’ve been talking about it in this newsletter for years at this point.

But we must pin down exactly where this bottleneck is. And one of those places is turbines. Demand for turbines is at an all-time high, and lead times from Siemens, Vernova, or Mitsubishi can reach up to 7 years.

Many power plants use turbines to turn heat into electricity. In steam plants (coal, nuclear, many biomass and geothermal plants), fuel or heat sources boil water into steam, which expands through a steam turbine, moving it. In gas plants, natural gas is burned with air and the hot combustion gases expand directly through a gas turbine, too.

In both cases, the turbine shaft spins the rotor of an electric generator. The rotor carries a strong magnetic field and rotates inside stationary copper windings, so the changing magnetic field induces an alternating voltage (Faraday’s Law) and current that can be sent onto the grid. Bottom line, we heat stuff to create electricity.

The rotating magnet induces current.

Acknowledging this and the urgent demand for new power has made natural gas turbines one of the most important commodities on the planet today, with some buyers even repurposing half-century-old turbines.

At the center of this rise in demand is, of course, the big AI data centers, which are asking utilities for hundreds of megawatts of firm, 24/7 power in places where the grid cannot deliver that much, that fast.

As waiting times to connect to the grid are too long, one response from hyperscalers has been to stop waiting for the grid and build their own “behind-the-meter” power plants right next to the data centers, often using aeroderivative gas turbines derived from old jet engines.

Arrays of these mid-size turbines are attractive because they are modular (tens of MW each), can be shipped and installed relatively quickly, and can follow load better than giant conventional plants.

Source: Semianalysis

But the current fleet is based on 1970s engine cores, is supply-constrained, performs poorly in hot weather (not designed for it), and usually needs a lot of cooling water. That’s the niche Superpower is targeting.

Boom’s Superpower is a 42 MW natural-gas turbine in a container-sized package, designed specifically for large behind-the-meter loads such as AI data centers, and can be installed and commissioned roughly two weeks after the pad, gas, and electrical hookups are ready, and has much shorter lead times than previous generations of turbines.

And the fact that this is a “supersonic engine” is directly relevant. The core was designed to run a Mach 1.7 airliner at 60,000 ft, where effective temperatures are around 160°F (71ºC), while legacy turbines were designed for subsonic cruise, where effective temperatures are around −50°F (-45ºC)… in a place like 110°F (43ºC) Texas summer.

Moreover, Scholl claims that four Superpower units can do the work of seven legacy turbines in the field and without cooling-water infrastructure. That translates into more delivered megawatts per unit of fuel, less capex per effective MW, and more predictable performance during heat waves, when both the grid and AI loads are stressed.

People are going to make a lot of money in 2026 by simply doing what we’ve known for more than a century: moving electrons.

AUTONOMOUS DRIVING

Incredible Insights into how Waymo’s work

Waymo, a Google subsidiary that is by far the most successful autonomous-driving company the world has ever seen (over 100 million miles of fully autonomous driving) and that is getting to London in 2026, has published a blog post that gives many details on how its models work.

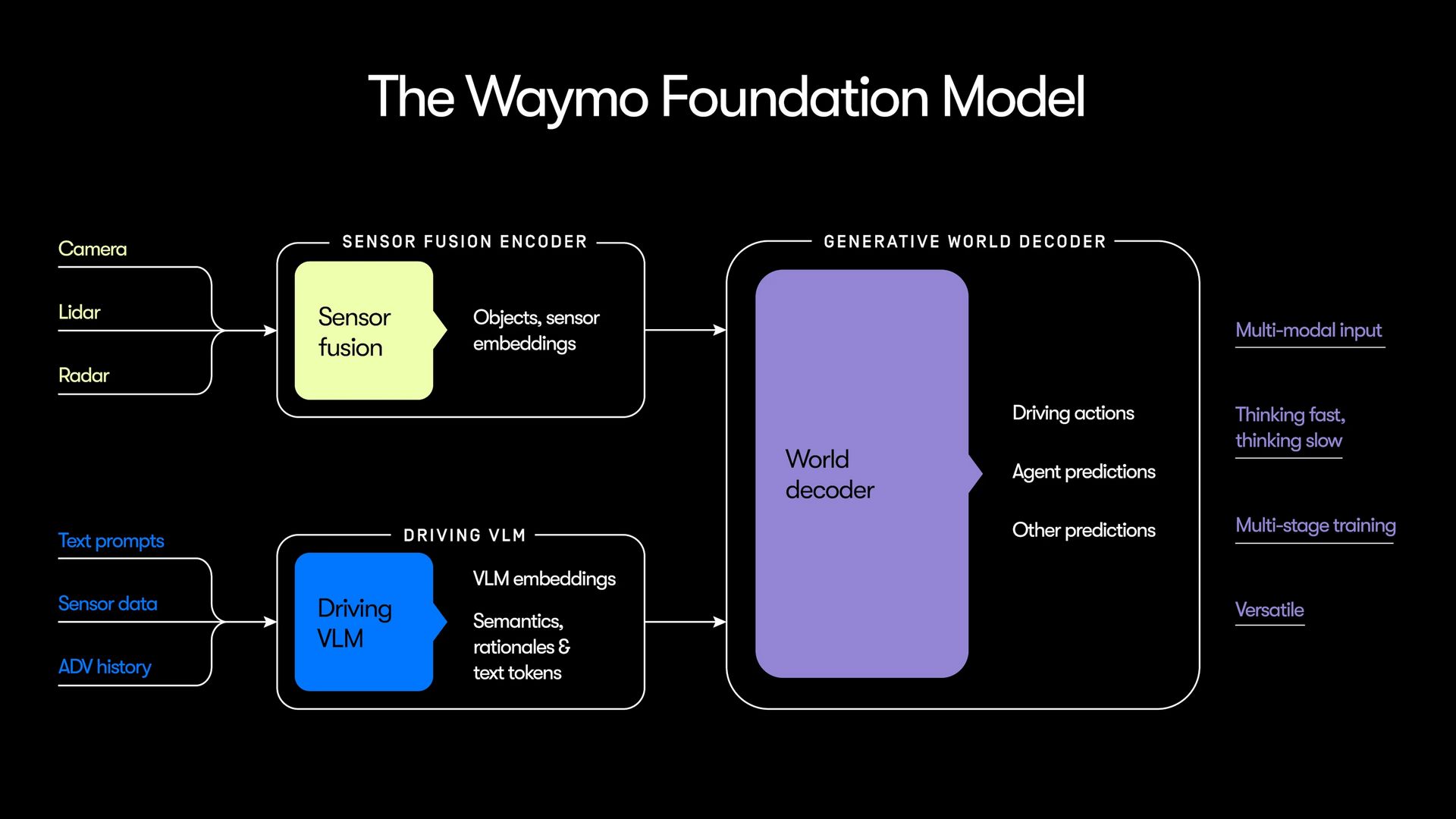

To the surprise of no one, at the core of Waymo’s technology is an AI model. Specifically, a world model.

But what is that? World models take the current state of the world (and sometimes a small portion of the past) as input and predict what will happen next. That is, in this case, it receives feedback of the state the car is in, and decides what the next move is.

This applies to the human brain, too. For instance, if you’re in a car and you see a deer on the side of the road, the deer may try to cross next. So before the deer actually crosses, your brain is already fully locked in, prepared to swerve if the deer does, in fact, cross. Hence, our brain is a world model.

World models are compelling because, unlike most AI models, they thrive in uncertainty. Most AI models today are not prepared to operate in partially observable, highly uncertain environments (e.g., estimating whether the deer will cross).

In LLMs, we can measure the uncertainty of a prediction too, measured by the probability distribution of the model’s response (i.e., if the LLM assigns 99% to the next word being ‘play’, it’s very certain. If the highest probability is 20%, the LLM has literally no idea what happens next). But their use as world models is largely debated considering they are trained on text, not real-world data.

Thus, as you may have suspected, Waymo’s foundation model is not an LLM, at least not totally.

For starters, it’s an AI whose output is driving actions, not words, obviously. But it’s a little bit more complicated than that.

Just like we are seeing in areas like robotics and basically any AI segment working with ‘embodied agents’ (AIs that have a “body”), it’s a “thinking fast and slow” model. That is, it’s a two-piece model that performs predictions at two very distinct frequencies:

A fast part focused on rapidly identifying and making decisions

A slower part focused on high-level planning.

For instance, the slow part may output actions at 300 Hz (300 actions per second) while the other may output 7 or 8 actions per second, or perhaps even slower.

Waymo has not disclosed the actual output frequencies.

This is “similar” to how our brains take actions. While driving, your hands may make several subtle movements per second to keep you on course, or even rapidly change lanes when a madman comes up from behind. Simultaneously, your “conscious self” may be thinking several seconds ahead that it’s about to switch lanes to pass a slower car ahead of you. This is the exact action distribution this two-piece model is striving for.

From a technical perspective, the faster thinker uses a combination of LiDAR (the basic idea is that a lidar unit emits laser pulses and measures how long they take to bounce back from surfaces) and camera inputs to quickly update the car's current state (road, weather, other cars' positions, etc.) and automatically takes action based on that input toward a specific goal (reaching the destination without crashing).

They call this sensor fusion because they are taking inputs from very different sensors into a single rich representation of the world’s state. This is probably the most significant difference from the Tesla Robotaxi, which is vehemently against LiDAR and relies solely on cameras.

As for the slower thinker, it’s a vision-language model, an LLM equipped with the ability to see images (frames from the cameras). This model is literally an LLM (Gemini) that has been fine-tuned for driving reasoning, that reasons ahead of time (e.g., “in a few moments, we’ll hit the car ahead of us if we don’t switch lanes or slow down”) to make more well-reasoned, high-level decisions.

The other big thing to expand on is the insights into the three different AI models they use for training.

Driver. It’s the model that actually drives the cars.

Simulator. A video-generation model, similar to the idea that NVIDIA presented with Cosmos Dreams, capable of generating high-fidelity car scenarios that are not real but appear to be, to give the driver more examples to work with.

Critic. This model evaluates the Driver's actions and provides feedback on how they could have been done better.

This creates a pretty powerful data flywheel, where Waymo cars deployed in production gather data, which is then used, in conjunction with the Simulator and Critic systems, to improve models continuously.

Waymo is very clear that models are not trained online. In other words, the model isn’t learning at the same time it’s driving you to your favorite bakery, and instead is trained “offline”, with the new model only coming live with new software updates.

Another question you may be asking yourself is: but is the model inside the car or in a cloud environment?

Luckily, it’s the former. As with most models deployed in production these days, even for products like ChatGPT, the models that actually drive cars are smaller, distilled versions of the larger, smarter models, which are essentially used as teachers to train smaller, thus runnable locally, models.

TheWhiteBox’s takeaway:

Overall, a kind of expected reality regarding autonomous driving software, but it’s always nice to see actual proof that gives us insight into how one of the most powerful AI systems on the planet works.

THEWHITEBOX

Trump Greenlights Sales of H200 to China

In a pretty remarkable turn of events, NVIDIA seems to have been successful enough in lobbying the US Government to relaunch its sales to China, and using none other than NVIDIA’s most powerful prior-generation GPU, the NVIDIA H200, a pretty strong AI chip for all intents and purposes, as long as the US Gov takes a 25% cut of the sales.

The H200 is far above the previous US export-control line: its performance is roughly 10 times that of the main regulatory threshold for advanced GPUs, and it’s also about 6 times more powerful than Nvidia’s previously approved H20 chip for China.

Trump claims CCP (China’s Communist Party) President Xi Jinping responded positively, but reports have emerged that the CCP is actually discouraging Chinese Labs from purchasing these chips, in fear that this will slow down their own chip design and manufacturing ambitions (China is fully committed to being totally self-sufficient with regard to all things AI).

TheWhiteBox’s takeaway:

Whether this is a good decision or not largely depends on whether you believe China will become self-sufficient in chip design and manufacturing. I think they will, so I don’t see the issue in letting them buy H200s.

As China analyse Poe Zhao has said “China will buy H200. China will use H200. But China will not bet its future on H200.”

On the other hand, compute is by far the most significant limiting factor for Chinese AI Labs; a well-served ecosystem of Chinese Labs could outcompete US Labs.

As I always say, in the US/China AI wars, the US’s moat is product, not the AI itself. On apples-to-apples comparisons, Chinese models are as good as Western ones.

But when you factor in that inference-time compute (deploying more compute per task), which is the most significant performance driver, the user experience with ChatGPT or DeepSeek’s app is like night and day because DeepSeek has far less compute and thus is forced to deploy lower thinking thresholds, irremediably impacting performance.

So yeah, you could certainly be skeptical of this decision if you truly believe it will allow China to load up on compute. However, does the US have a choice? China is the unequivocal bottleneck in rare Earths (careful, on refining, not on material availability, rare Earths are, funnily enough, not rare), and if China cuts that supply, there are no chips, no matter how good your design capabilities are.

MEMORY

SK Hynix, Upcoming US Listing?

Sk Hynix, the world’s leading supplier of High-Bandwidth Memory (HBM), and NVIDIA, AMD, and Google’s main supplier of this technology crucial to their XPUs (AI accelerators), is seriously considering listing in the US.

SK Hynix shares jumped 6.1% on December 8 after reports that the company is moving toward issuing American Depositary Receipts (ADRs) and selecting underwriters. The market is betting that US trading of SK Hynix equity could help close its valuation gap with US rival Micron, with one analyst suggesting roughly half of that gap could re-rate quickly once the ADR plan is formalized, and more over time as the issuance proceeds.

In practical terms, an ADR is a certificate issued by a US bank that represents shares of a foreign company the bank holds in custody. The ADR trades in dollars on a US exchange just like any other US stock, while the underlying “real” shares remain listed in the home market. For US investors, ADRs remove friction: no need to deal with foreign exchanges, currencies, or settlement quirks.

For SK Hynix, a US ADR could bring higher liquidity, make stock-based compensation more attractive when hiring globally, and deepen ties with US partners and investors.

TheWhiteBox’s takeaway:

Despite SK Hynix being a better business, the fact that it’s Korean rather than US-based means it has a lower valuation than Micron, a perfect example of the advantages of being listed in the US.

Investing in SK Hynix is very complicated for US citizens, as direct purchases of SK Hynix stock are a rare sight. Consequently, most investors gain exposure to SK Hynix either by buying into prominent semiconductor ETFs, buying the Korean Index (SK Hynix is one of the largest by share), or buying through the German GDR listing, HY9H.

For all these reasons, this news by itself could boost the stock simply by the fact that it opens it to new markets and also puts into serious question the disparity in valuations between them and Micron.

MEMORY SHORTAGES

Even Samsung is Memory Constrained.

You know things are bad when even memory chip manufacturers are supply-constrained.

News is circulating that Samsung’s mobile chief, TM Roh, will urgently meet Micron’s CEO on CES 2026 day one to secure LPDDR5X DRAM for Galaxy S26 after prices jumped 133% ($30 → $70 for 12GB) in 2025. Contracts are still unsettled, Exynos production is cut, and S26 shipments risk delays.

TheWhiteBox’s takeaway:

Yes, you read that correctly. Access to memory chips is so constrained that Samsung’s semiconductor division (where memory chips are manufactured) can’t even provide memory chips to its mobile division.

The issue is that Samsung’s semis division is too focused on HBM for AI clients, so it's unable to provide LPDDR5x memory (the DRAM used in Samsung’s smartphones) for its own products (its smartphones).

Based on news like this, it doesn’t take a genius to foresee the rise of smartphone prices across the board in 2026, and not by a small margin.

DEEP RESEARCH

Mistral Releases Devstral 2. It’s actually impressive

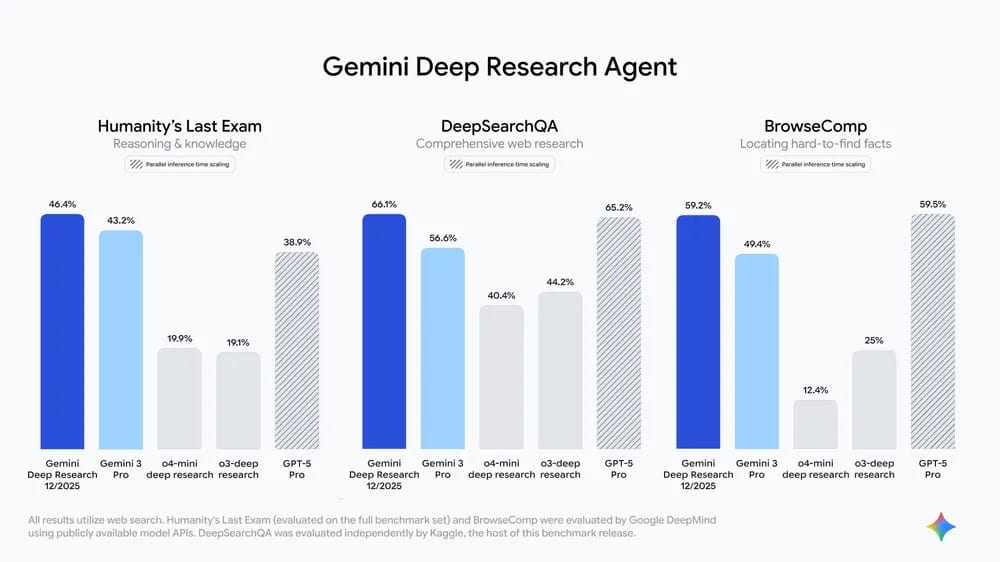

In the wake of OpenAI’s GPT-5.2 release (see below), Google has unexpectedly released a new version of its Deep Research agent that sets new state-of-the-art results on research tasks, promising better performance than GPT-5 Pro despite being offered in the Gemini Pro subscription (GPT-5 Pro is only accessible in the $200/month ChatGPT Pro subscription), giving also access via the Interactions API, a new API released today too.

TheWhiteBox’s takeaway:

It’s not yet accessible through the Gemini app, but it will be soon. I highly doubt it’s better than GPT-5 Pro, let alone the 5.2 model below, as per my recent experience with the Gemini 3 Pro Deep Think agent, OpenAI’s Pro model is still leaps and bounds ahead of the rest.

And talking about GPT-5.2…

FRONTIER MODELS

OpenAI Launches GPT-5.2

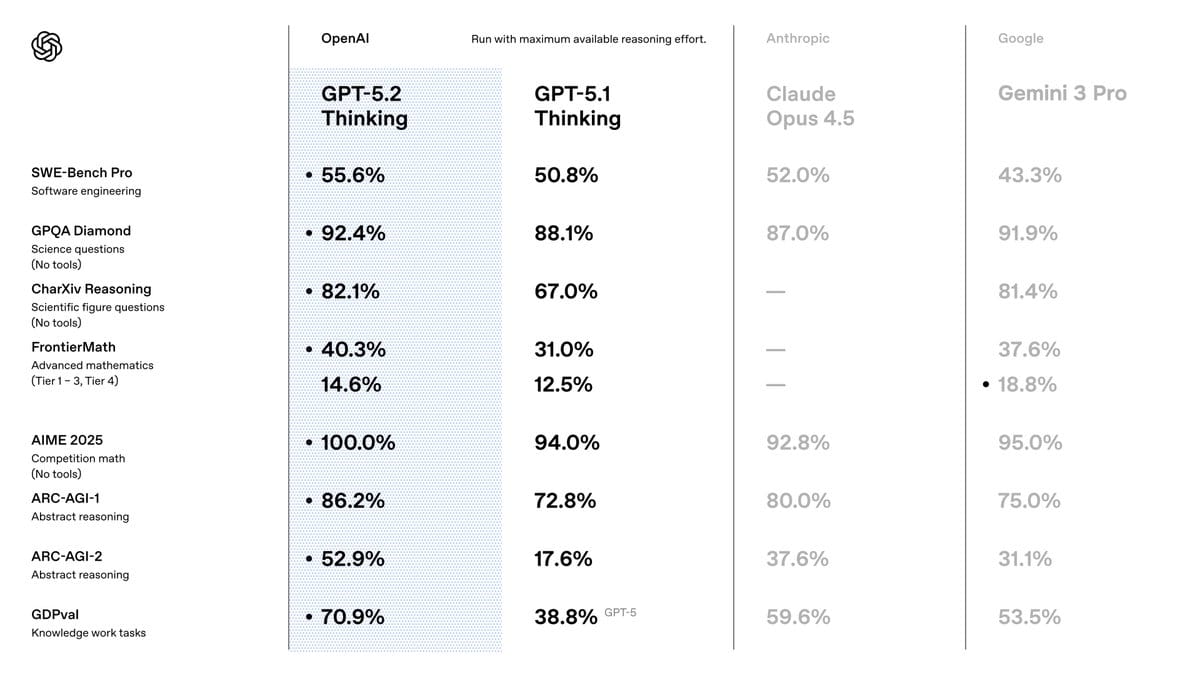

Frontier AI Labs won’t give me a break. This time, it’s OpenAI releasing GPT-5.2, the first model to score a 100% in AIME 2025, while also getting huge scores in other relevant benchmarks like ARC-AGI (IQ-like puzzles) or SWE-Bench Pro (coding).

The model appears to be clearly superior to the 5.1 version and enjoys a significantly updated knowledge cutoff of August 31st (meaning the model has seen data up to that date, without relying on search APIs to access those events).

TheWhiteBox’s takeaway:

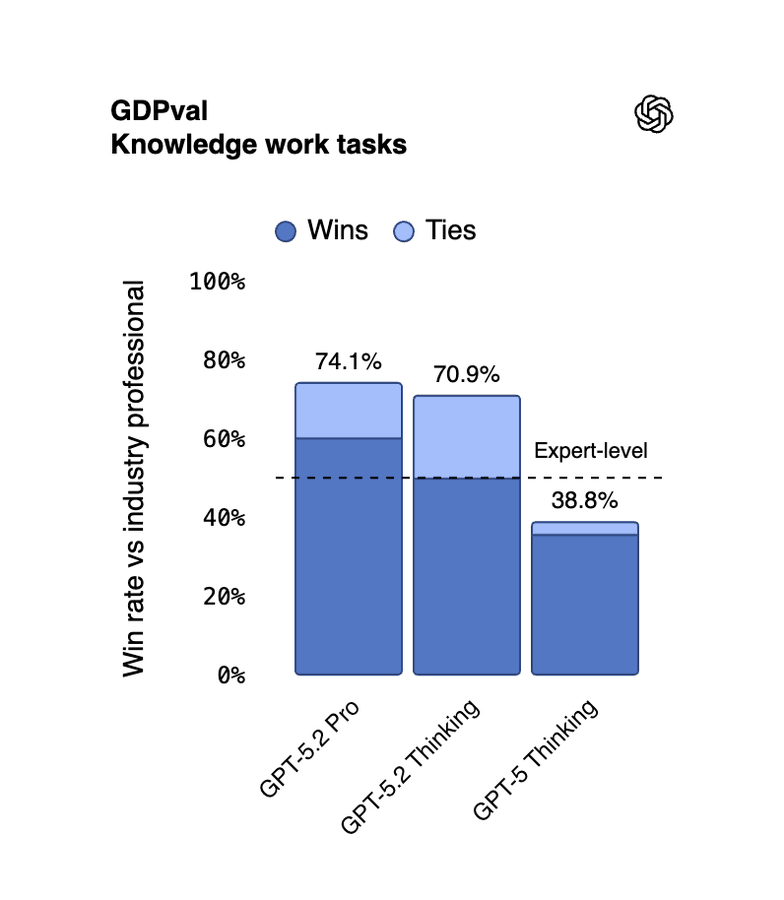

The model literally came out seconds before I typed these words, so I can’t really comment on anything beyond what OpenAI is claiming. Yet, the claim that caught my eye was that this model is the first model to perform at a human level in knowledge work tasks as measured by OpenAI’s own GDPval benchmark, one that is less about models being maths savants and instead being useful in day-to-day knowledge work.

Overall, I wouldn’t be surprised if this model is instantly the best thinking model on the planet. From my personal experience, OpenAI sucks at non-thinking models, but their reasoning versions are truly exquisite. The jury is out on this one, but of course, it looks good.

CODING

Mistral Releases Devstral 2. It’s actually impressive

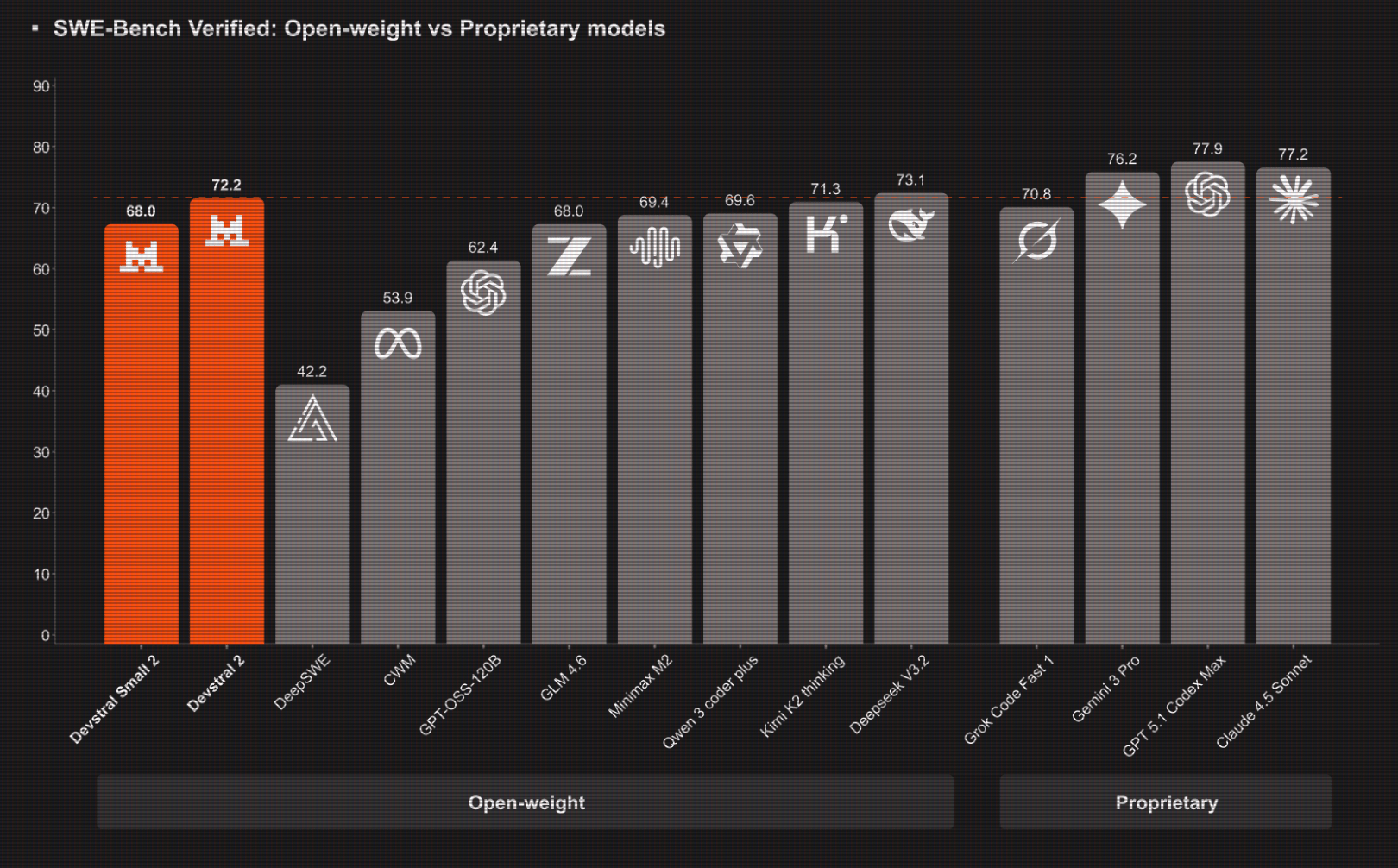

Mistral has released Devstral 2, a new open-source coding model family (123B and 24B parameters, 256K context window models) that achieves 72.2% (small: 68.0%) on SWE-bench Verified and targets agentic code workflows with strong cost-efficiency versus proprietary models.

Devstral 2 is free via API for now and will later be priced at $0.40/$2.00 per million tokens (input/output), with Devstral Small 2 at $0.10/$0.30.

They also launch Mistral Vibe CLI, an Apache-licensed terminal agent that can explore, edit, and run code across projects with project-aware context, multi-file orchestration, and tool integrations, configurable to use Devstral models locally or via API.

TheWhiteBox’s takeaway:

While the large model is pretty much obsolete on release, as the price isn’t low enough to not simply use DeepSeek v3.2 which is way cheaper, or pay a little bit more and get best-in-class performance with Google’s Gemini 3 Pro or even Anthropic’s Opus 4.5, the highlight of the release is the small model, which offers extraordinary coding capabilities for a model that fits into beefy consumer hardware, requiring ~50 GB of RAM (requires computers on the higher end of RAM, in the 90 and up range, but that’s still possible on consumer hardware today, like my own computer).

That said, the models are presumably slow for their size, considering they are dense models (they aren’t sparse MoEs, as most frontier models today are), which could mean that even though they are smaller than most frontier models, the latter could actually be faster despite being much larger.

But this is a good release considering it’s a European Lab. I mean, we now have a top coding model for local tasks coming from Europe, or let me put it this way: there’s now a reason to use a European model for something. At least it’s not the mediocre showing they had with Mistral Large 3.

ROBOTICS

1-hour Footage of Figure 3

AI robotics continues to progress. This time, it’s an hour-long footage of FigureAI’s Figure03 robot working, with no mistakes, on a conveyor belt.

Here, the robot is tasked with individualizing each package, finding the barcode, positioning it facing down (for a label to be added to the top), and centering it on the conveyor.

This is very, very impressive. But why?

TheWhiteBox’s takeaway:

You may feel underwhelmed by the apparent simplicity of the task, but boy, would you be mistaken if you felt that way. This is actually remarkable and a clear candidate for state-of-the-art robotics. The reasons for this are two-fold:

Moravec paradox

Robustness

The former is a universal law in robotics: what is easy for humans is very hard for robots, and vice versa. So if you feel underwhelmed by a robotics video because you think the actions are too easy, well, you should then be impressed because that means those actions are actually pretty fricking hard for robots.

But perhaps even more impressive is that the robot worked for an entire hour without making a single mistake while running the AI locally (the model runs on an embodied GPU).

The reason is that the robot’s brain, the AI, is a sequence-to-sequence model, meaning that it’s continually predicting the next action based on its current state and some previous actions and states (the CEO mentioned the model has some long-term memory, which means it’s not a Markov chain but has reference to past experiences).

A Markov chain is a system in which the following action is taken solely based on the most immediate action; it is a stateless model and the most common form factor in robotics.

So, in a way, this is just like ChatGPT; it predicts the next token based on previous ones, but it predicts robot actions rather than words.

The problem with these architectures is that errors propagate and accumulate. As previous predictions are fed back into the model to predict the next action, if the last prediction was a mistake, it’s much more likely that the next prediction is a mistake too.

To prevent this, you need to bake into the model’s self-correction capabilities, which is something FigureAI has been showing off for its models for a while now, but is actually pretty hard.

Furthermore, robots need to show robustness across independent tries. If an AI gives you 90% accuracy per try, for several consecutive independent tries, the overall performance falls down a cliff.

For instance, if the accuracy is 90% on one try, the chance the model does 10 consecutive tries correctly falls to 34%. And the number drops to 0.0026% for 100 successive tries.

Therefore, the fact that the model got perfect marks on what seems to be hundreds of consecutive tries is remarkable. For instance, say the model made a mistake on the 500th successive try. That means it still has an accuracy of 99.998%, more than four nines.

Lab tests are fun, but until we show at least four, and preferably five, nines in reliability (99.999% accuracy), AI robots are toys, not products.

Thus, achieving a one-hour error-free demonstration is impressive and indicative that we might be inches away from production-ready humanoids (production-ready robots have been a thing for a while now, but there’s very little evidence of humanoids in production settings, if any).

Closing Thoughts

Another intense week packed with insights. From having the first real proof that GPUs might actually work in space to crucial insight into Waymo’s brains, the industry continues to prove it can still innovate on a weekly basis.

In markets, the memory shortage cycle becomes more apparent by the day, and Sk Hynix’s potential move into the US through an ADR listing is suggestive of them being convinced that the memory supercycle is upon us. That memory stocks might become the new darlings of the AI trade. And just as I was sending this newsletter, Disney announced a $1 billion investment in OpenAI and a licensing deal for its characters in Sora.

And on product, Europe has presented the first worthwhile model in a while in Devstral 2 small, ideal for beefy local setups, and Figure AI has presented quite possibly the most impressive robotics demo in months, showing the big missing piece in robotics, robustness, may be solved soon.

And to top it all off, this week we also have TheWhiteBox Portfolio section, where we are revisiting one of our most important investments, but from a new, very interesting point of view, in how agents might be a particularly bullish factor for a particular chip company based on the most unexpected of realizations:

With AI agents, the performance bottleneck is not the one you might believe. And that screams opportunity.

Give a Rating to Today's Newsletter

For business inquiries, reach me out at [email protected]