Predicting the Future of AI Hardware

One of the most significant, yet underestimated, changes in AI over the last year has been that, for the first time, software is dictating how hardware is built, meaning understanding how AI looks inside automatically gives you “predicting powers” to foresee the future of AI hardware.

This is no joke, considering AI hardware is by far the most dynamic and opportunity-rich market in AI these days because, well, it’s the only one where money is being made and thus where most investors flock to.

But if I put you on the spot today, would you be able to answer how AI workloads are structured, how hardware works, why software now calls the shots, and ultimately, what will hardware look like two years from now?

If the answer is no, you can't consider yourself someone who truly understands AI. Luckily for you, by the end of this piece, you will:

Fully understand the principles of how AI data centers work in great detail, but without jargon, to answer: Why do we need AI data centers to be so large?

Comprehend the critical transition we are seeing from chips to systems, and key players that stand to benefit inside and outside of Big Tech.

Learn about the ‘Five Horses of Change’, the five significant changes in AI that are literally driving NVIDIA or AMD’s product roadmap,

And how China will weaponize software-driven hardware to outcompete the US, and how this poses a real risk to the US dollar's hegemony.

Let’s dive in.

How can AI power your income?

Ready to transform artificial intelligence from a buzzword into your personal revenue generator

HubSpot’s groundbreaking guide "200+ AI-Powered Income Ideas" is your gateway to financial innovation in the digital age.

Inside you'll discover:

A curated collection of 200+ profitable opportunities spanning content creation, e-commerce, gaming, and emerging digital markets—each vetted for real-world potential

Step-by-step implementation guides designed for beginners, making AI accessible regardless of your technical background

Cutting-edge strategies aligned with current market trends, ensuring your ventures stay ahead of the curve

Download your guide today and unlock a future where artificial intelligence powers your success. Your next income stream is waiting.

The Principles of AI Software

We could go as detailed as we wanted to explain the intricacies of Artificial Intelligence, or AI, but we don’t need to get into the gradient descents, embeddings, and optimizers today.

Luckily, to make successful inferences about AI’s future, to understand what will happen next, and why Hyperscalers feel the urge to spend another $500 billion next year on AI, we just need to learn the first principles, by starting from the most basic question almost no one can answer correctly: How and what do AIs learn?

Compression

Most AI models today, at least the most popular ones leading the biggest corporations on the planet to invest a combined trillions of dollars, are artificial neural networks (ANNs), a particular type of AI software.

ANNs are compressors, algorithms that are capable of seeing a lot of data, learning from it, and making predictions.

These predictions are then compared with the correct answers, and we use this signal to improve the model over time by pulling them closer and closer to the ground truth.

The key is that, by the way they are structured, these models can capture the patterns that govern the behavior of data. They cut through the noise to answer: from the data I’m seeing, what moves the needle and what doesn’t?

Using a simple example, say we want to predict the price of a random house. A totally uncompressed process (or ‘unintelligent’) would be a database where we store housing data, storing every piece of information we can, along with the price, and then do some statistical analysis ourselves to identify which variables affect the most, maybe even by running a regression.

Databases store data that you can retrieve, but they are unopinionated about what data really has predictive power (i.e., out of all the datapoints, which ones are most indicative of the price of a home?)

Instead, a neural network doesn’t store every single possible detail, but only those that matter. A database may store thousands of data points, while the NN will store only those that actually explain its price (postal code, size, number of bathrooms, etc.).

We call this compression: the capability of eliminating the noise and just storing what’s essential. This pattern-identifying capability allows them to be much smaller than the dataset they learn.

For instance, when we look at Large Language Models (LLMs), they are sometimes three or even four orders of magnitude smaller than the datasets they can represent (i.e., 1,000 or even 10,000 times smaller).

But how? Again, capturing patterns. In LLMs, which are mostly trained on text, they eventually pick up things like grammar and how words correctly follow one another according to language rules.

And from the moment they understand grammar, the infinite possible combinations of words in English get narrowed down to only those that are correct. But it’s not just grammar; they can pick various patterns that refer to knowledge too (capital city → country), maths (how to add up numbers without memorizing), etc.

However, there’s a problem: models, even modern generative ones, are mostly trained by imitation. That is, they learn data by seeing it repeatedly and copying it.

And although this has started not to be the case over the last year, as AI Labs are experimenting with trial-and-error learning (i.e., instead of showing them the solution to copy, they force models to find it themselves, a process known as Reinforcement Learning, or RL), it’s safe to say models are still heavily dependent on this imitation phase.

And lately, we are doubling down on this. AI’s last frontier model, Gemini 3 Pro from Google, not only did not reduce the imitation phase, called pretraining, but expanded it even further. And even more recently, OpenAI’s Head of Research acknowledged that they are significantly expanding pretraining efforts after a year of experimenting too much with trial-and-error learning.

But what is the issue with imitation learning? Well, because it’s clearly not the best approach to incentivize the emergence of real intelligence, as it makes it too easy for models to simply memorize the data.

Memorization vs Intelligence

Memorization is not intelligence; it’s memorization. Intelligence can be framed as the ability to learn patterns that can be applied to new data or new scenarios, a behavior we formally describe as out-of-distribution generalization.

Or as Jean Piaget would put it, “what you use when you don’t know what to do.”

Which is to say, we are still being mostly fooled by AI models that appear intelligent when, most of the time, they are mostly regurgitating patterns they’ve seen multiple times.

Using our earlier database comparison, despite there being definitely some compression going onf, they are still closer to databases than to real intelligent entities like humans.

So what do Frontier AI Labs do when they run into this wall? Easy, make datasets larger and thus make models larger too.

This is the famous in-distribution generalization trick, aka “if we can’t make models perform with unknown data, let’s make sure no data is unknown to them.”

And that is the key thing I wanted to get to; all this explanation was to tell you that models are getting bigger and will only get much bigger.

Okay, so what?

Well, simple: Because this is the first reason why hardware is being governed by software; what matters is not the chip, it’s the system.

From XPUs to Data Centers

To understand what an AI data center is and how software changes are modifying how we build AI data centers (and how big they get), we first need to explain once and for all what an AI workload is by describing how most frontier models look like today: sparse MoEs.

The most popular model today: Sparse MoEs

What is an AI workload? That question is obvious to ask, yet you’d be surprised how almost no one can actually explain it in detail. Let’s fix that.

The most important thing to understand about AI workloads is that they are always distributed because, well, models are big. We’ll take a look at training and inference workloads in a second, but in both cases, the model is distributed across several GPUs, which we define as ‘workers’.

Each XPU (a term encompassing all hardware accelerators like GPUs, TPUs, LPUs, etc.) has one or more compute dies (chiplets) and memory chips as well. Both are limited for each accelerator. Depending on which one is the limiting factor, you’re either ‘compute-bound’ or ‘memory-bound’. Most, if not all, AI workloads today are memory-bound.

As I’ve explained countless times, and most recently here a few days ago, the type of AI models everyone is thinking about when discussing this massive AI buildout are Transformers, which are just concatenations of ‘Transformer blocks’ formed by two types of layers: attention and MLPs.

Attention layers process the words in the sequence (how they relate to each other) to form an understanding of what the input says.

MLPs are responsible for adding knowledge that the model has internalized during training.

For example, for the sequence “The capital of France is…”, attention layers identify what the question is, and that we are speaking about France, and the MLP layers tap into the model’s knowledge, helping the word ‘Paris’ emerge.

Many people use to compare both to a human’s short-term and long-term memories. The attention layers are the short-term memory, and the MLPs tap into the model’s knowledge, or long-term memory.

We don’t have to go any deeper than this (in the previous link, I go into great detail explaining how all this happens).

Instead, it’s enough if we just understand one thing: ‘most frontier models today are sparse MoEs’. That is, most frontier models today are a variation of this architecture known as an ultra-sparse mixtures-of-experts (MoE) autoregressive LLM.

Yeah, I know, that was a mouthful. Luckily, it’s pretty intuitive, actually.

If we picture the MLP layers as the model’s long-term memory, in MoEs, we break these layers into smaller pieces from the very beginning, forcing the model to allocate knowledge in smaller compartments instead of having everything stored everywhere, which become ‘experts’ at different topics.

Think of this from a brain perspective; you can either have a vast pool of memory you can use every time you need to retrieve something, or you can willingly break it into parts and force each part to specialize in certain topics.

The advantage of using MoEs is that, during inference, an internal router decides which experts to query (i.e., which part of the model’s long-term memory is best for answering that question) and prevents the rest from activating.

This introduces the idea of ‘activated parameters’, which refers to the number of model parameters that are actually activated for any given prediction.

This is crucial because it allows us to run huge models at small-model compute requirements. For example, if you take Chinese Kimi K2, it’s a one trillion parameter model with 36 billion active parameters, so only 3.6% of the total model activates for any given prediction.

But why do this?

There’s more to this (there’s a reason we don’t just train a small model and call it quits), but think of this as running a super smart model at the compute requirements of a smaller one, or vice versa, running a small model with the “intelligence” of a large one.

And to the surprise of no one, ALL modern frontier AIs are sparse MoEs, meaning models are huge yet run like small models.

For this reason, sparse MoEs are the default these days. All frontier models, and I mean all, are sparse MoEs.

However, despite being capable of running models much faster, MoEs don’t address the bigger issue: memory bottlenecks, as both the model and the sequence’s cache get pretty big either way.

What is this ‘cache’? During inference of autoregressive LLMs (all frontier AI models today), we ‘cache’ (i.e., store) all the reusable activations. As they predict the response word by word, some of the computations required to predict the first word can be reused to predict the next, saving even more compute but increasing your memory requirements.

Luckily, there’s a solution: breaking the model and sequences into parts across several GPUs.

AI workload parallelism 101

We already know AI workloads are distributed. All of them. At this point, engineers have to decide how. The primary partition techniques used today are:

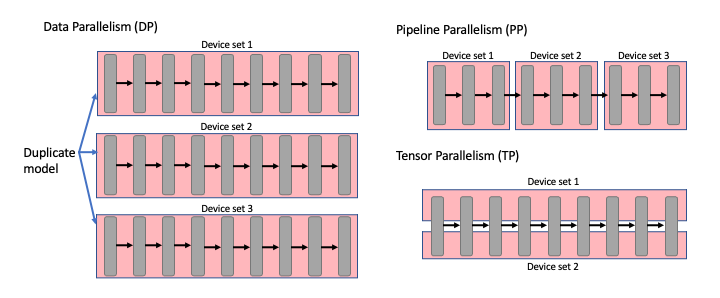

Pipeline parallelism (PP), where a model is broken up sequentially (e.g., a model with 20 layers and 5 GPUs is split into five, four-layer groups). Here, a GPU’s output is the input of the next one.

Tensor parallelism (TP), where we break the model “sideways” (e.g., we have 20 layers and two GPUs; we take half of the layers and send them to one GPU, the other half to the other). Here, both GPUs share the workload and communicate after every layer.

Data parallelism (DP), where a model encapsulated by unrelated groups of GPU workers is fed different data sets. As they are independent, no communication is needed during inference (that’s not the case for training, as we’ll see in a second).

Context parallelism (CP), where models share the sequences. For instance, you might send a 1,000-token sequence to a model, but processing your sequence might be handled by 5 GPUs with 200 tokens each.

Expert parallelism (EP), where models are sent different sets of experts in a mixture-of-experts model (more on this in a second). Very popular these days.

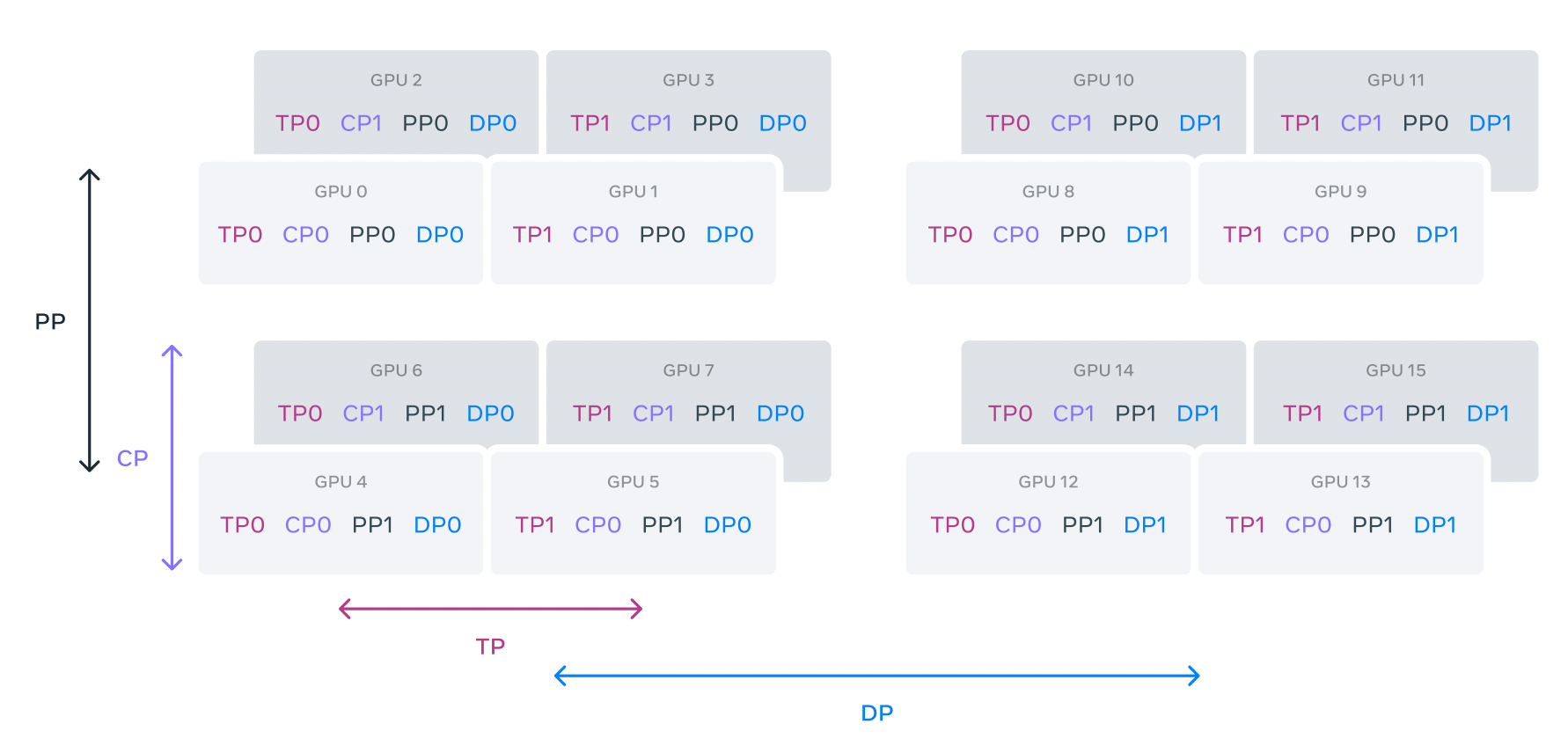

But which ones do we use? Well, all of them at the same time. If we look at how Meta trained the Llama 3 models, one of the seminal open-source releases, they use all the above except for expert parallelism (Llama 3 for a dense model, meaning it was not an MoE).

As you can see below, one of the options Meta considered for its GPU cluster was grouping into 64-GPU blocks, each of which was subsequently divided into 16 4-GPU blocks. But how do we make this graph make sense?

More specifically:

We have two pipeline-parallelism groups (PP0/PP1). For each data-parallel replica, four GPUs handle the first half of the model’s layers and four GPUs handle the second half. Pipeline parallelism lets us spread the layers across GPUs, but each half of the model is still huge on its own.

However, this isn’t enough parallelism. They were using NVIDIA H100s, each with “just” 80 GB of HBM memory. The Llama 3 405B model was about 810 GB in bf16, so even if we divide it into two pipeline stages, each stage still contains around 405 GB of weights. That clearly cannot sit on a single 80 GB GPU. In practice, that 405 GB chunk is further sliced across the GPUs that belong to that pipeline stage, so each GPU only keeps a fraction of that half of the model, on the order of tens of GB of parameters, which is small enough that it can coexist with activations and other states.

We then add tensor parallelism (TP). Here, within each small tile of GPUs, pairs of GPUs split each large weight matrix between them: one GPU holds one slice of the tensor, the other GPU holds the complementary slice, and they work together as if they were a single larger device (if PP breaks the model’s length into pieces, TP breaks the model’s width into pieces). This further reduces the amount of parameter memory each GPU needs for a given set of layers.

Finally, they add two other kinds of parallelism: data and sequence (often called context) parallelism. Data parallelism means that each replica of the model sees a different shard of the training batch. Sequence/context parallelism means that, for a given long training text, different GPUs handle different chunks of the token sequence.

In summary, a single GPU ends up holding only a small slice of the model’s parameters and a small slice of each input sequence, while different replicas see different slices of the data.

All in all, they trained Llama 3 by breaking models in both dimensions (across the model’s length and width) and by partitioning data and sequences (meaning a text sequence would go to only half of the GPU network and would be further broken down into pieces).

This is just one example, as today's workloads, which are all MoEs, are partitioned even further with expert parallelism (EP).

For instance, in the case of DeepSeek’s v3 training run (and subsequent 3.1 and 3.2 models, the latter of which I recently covered), they perform 64-way EP, meaning the model’s experts are broken down into groups of 64 (e.g., if we have 128 experts per model, each GPU out of the 64 gets two experts).

But even if we now understand parallelization techniques much better, we would still fall short of understanding how AI data centers are built today if we don’t explain the differences between training and inference.

Training v Inference Workloads

The parallelization techniques are what they are, but we use them differently depending on the workload.

When training AI models, the amount of training data is so unbelievably large that our biggest bottleneck is getting through the entire data in a “human lifetime”. Wait, what? An example will make it make sense.

For instance, say we want to train a small model that, unlike Llama 3, fits in a single GPU. Let’s also suppose we want to give it training dataset with a total compute budget of 1025 FLOPs (meaning the model has to perform 1025 operations to go through that training data).

This sounds like a lot, but it is fairly small by modern standards (it’s approximately GPT-4’s training budget). If we took the most powerful chip in the world today, NVIDIA’s B300, with 9 PetaFLOPs of training performance (peak), assuming we could achieve such peak (we can’t), that GPU would require ~35 years to train a model on that “modest” dataset, and that’s assuming untenable peak performance.

Calculation: 1025 FLOP / 9×1015 FLOP/s = 111 × 107 seconds ~ 35 years. And assuming a more logical average peak performance of 50%, it's 70 years. Good luck with that.

By the way, there’s no way a GPU lasts for that long at those peak workloads; you would need to change it every 2 years and that’s being extremely optimistic.

Therefore, it’s not only a memory issue, but it’s also about sweeping through the dataset in a manageable time, at most a few months to avoid obsolescence risks (i.e., you could deliver a model that, by the time it is deployed, is already obsolete).

Consequently, we need large training clusters for a single model training run, with modern workloads requiring hundreds of thousands of GPUs per run.

Therefore, in training, the more GPUs we have per workload, the better.

Inference is another story. Funnily enough, quite the opposite, actually. Unlike in training, where you’re bottlenecked by total training run length, in inference, per-sequence latency is the primary concern, because you have a user waiting on the other side.

Here, slow inter-GPU communication is a significant problem, so we want to ensure the GPUs working on a user’s request are closer together, ideally in the same physical rack.

Hence, in inference, the less GPUs we have per workload, the better.

But do not confuse this with having small AI servers. Actually, as we’ll see in a minute, we want them to be huge! At this point, you may feel confused, but that’s because we need to differentiate between servers, clusters, and data centers to make sense of it all. This introduces us to the three primary metrics you need to know about AI data centers:

Scale-up: How many GPUs can you link together in a physical rack (e.g., NVIDIA’s Blackwell Ultra server), or at most two physical racks (Amazon’s Trn3 NL72×2). In other words, your scale-up defines the size of your AI server.

For instance, NVIDIA’s Oberon architecture, with the Blackwell Ultra chip, has 72 GPUs connected in a single physical GPU rack. This is the crucial metric for inference, where we want to keep workloads inside the server.

When I said in inference we want the fewest GPUs possible, I meant we want to keep inference workloads inside a single server to avoid server-to-server latencies, but naturally, the more GPUs we fit in that server, the better.

Scale-out: How many AI servers can you link together. More critical for training, as we saw in the Llama 3 example, where 64 GPUs worked in unison, despite each physical server being 8-GPUs in size.

The problem with scaling out is that the networking hardware is slower than intra-server speeds, so you can grow to thousands of servers in total, but you take a hit in speed (this is why this is something to avoid in inference). As you can guess, this moves you from servers to clusters, which can be as large as the entire data center.

Scale-across: More prominent lately, it defines how many data centers you can plug in together. Again, irrelevant for inference but very important for multi-data-center training, with examples such as the Gemini 2 and 3 models, which were trained across multiple DCs.

But here we run into a “problem”: RL training. As you already know by now, if you’re a regular of this newsletter, frontier models today are all “RL-trained”, meaning they were trained using Reinforcement Learning on top of an LLM trained via imitation learning.

And the “problem” here is that RL mixes both worlds of training and inference. But how?

RL training and disaggregated inference

Let me put it this way: in RL training, all training is inference. Wait, what?

Here, the model is no longer imitating the exact sequence you want it to learn. Instead, you give it a problem, and the model has to find the solution by itself (we guide it using rewards that score good actions and punish bad ones, hence the name of RL, but the model is literally “trial-and-erroring its way into the solution”).

Okay, so?

Well, it’s pretty obvious; if you want to train the model, you first have to let it run (inference) until it finds the solution, an entirely inference-driven workload, and once it finds it, then perform the learning phase.

In practice, as you can see below in Mistral’s diagram of how they trained their reasoning model ‘Magistral’, this means we have to separate your GPU cluster into groups of learners and inference workers, where:

Inference workers (generators) generate the rollouts (the generations that are candidates to be learned,

Verifiers score the rollout, and trainers use those outputs to update the model, thereby modifying it with that new signal.

Finally, the new model is reloaded into the generators (the inference workers that generate the rollouts), and the process repeats.

And to enrich our confusion even more, generators (inference workers) can also be divided into prefill and decoding workers, because inside the inference stage itself, workloads are different enough between the two inference stages (prefill and decode) that you specialize GPUs for that, too. This is called ‘disaggregated inference’ and will become very important later in this piece.

In our coverage of Aegaeon, which I then expanded on in my Medium blog, we clearly see this distinction in way more detail. You can read that piece here.

And why am I telling you all this? With all we’ve learned so far, we can finally understand how hardware will change in 2026 and throughout the decade.

That is, we are now going to explain the five changes which I call the ‘Fiver Horses of Change’ happening in hardware and infrastructure, a beautiful executive summary that, in one shot, allows us to understand… basically the entire industry.

Understanding this is understanding the business strategies of NVIDIA, AMD, Amazon, Meta, Broadcom, Marvell, or Google, among others, and will help you position yourself better than most (including Wall Street analysts) for 2026.

After that, as a bonus, we’ll explain the biggest takeaway for me:

We’ll finally understand why China is pursuing open-source,

how it’s weaponizing it against the US,

And, perhaps most importantly, how this transition to software-driven hardware makes China’s open-source particularly deadly to the US and to its currency, the US dollar.

The Five Horses of Change

There are five ways in which hardware is changing based on software influences. Understanding these five ways enables you to predict what companies like NVIDIA will do over the next few years (at least throughout the decade).

1st big change, ad hoc logic

The first big change comes, ironically, from the lack of change. I’m referring to the Transformer, the underlying architecture that, as we’ve discussed, has remained essentially unchanged for the best part of the last decade and shows no signs of changing anytime soon.

Yes, we are seeing some cosmetic changes, like MoEs and, more recently, DeepSeek’s DSA attention, but it’s still mostly the same architecture.

In this regard, some companies are literally printing this architecture into the chip. What this means is that, unlike other accelerators like GPUs (more flexible, runtime scheduler) or TPUs (very specific to AI matrix multiplications, but still architecture-agnostic), this Application Specific Integrated Circuit (ASIC), like Etched.ai, is the most ASIC example you can fathom, a chip that is designed for models running this specific architecture and nothing more. If the architecture changes, this chip doesn’t work at all.

This is a very risky take despite the pervasiveness of this architecture, but extremely dangerous for incumbents like NVIDIA if the architecture does resist the test of time.

If correct, Etched could have an enormous throughput advantage over basically everyone, who are Transformer-pilled too (as we’ll see in a minute), but not enough to actually print the architecture onto the chip.

But if wrong, and the architecture paradigm shifts, your chip is useless.

For those reasons, this is the most asymmetrical bet: it’s huge for one company, bad for the rest. TSMC, memory, and networking players still benefit, but we’ll cover them in more detail in the other four sections.

And here we get to the most significant change and the one that could make you the most money in 2026.

2nd change, models get bigger and bigger

This one feels somewhat predictable, but it’s unmistakably not priced in by markets. Models are getting bigger and will only get bigger, with some voices saying modern frontier AIs have up to 10 trillion parameters.

So what?

Well, because it has caused the two most significant visible changes in AI hardware in years: increasing scale-up and per-GPU HBM allocations, both of absolutely immense importance in this industry.

Let me put it this way: Understanding this is understanding AI hardware.

It’s understanding AMD and NVIDIA’s strategies and potential stock performances.

It’s understanding who wins and loses the chip wars.

It’s understanding why Broadcom and other notable players matter a lot, too.

And, crucially, it’s understanding why I have chosen three companies as the big, big winners of 2026.

Subscribe to Full Premium package to read the rest.

Become a paying subscriber of Full Premium package to get access to this post and other subscriber-only content.

UpgradeA subscription gets you:

- NO ADS

- An additional insights email on Tuesdays

- Gain access to TheWhiteBox's knowledge base to access four times more content than the free version on markets, cutting-edge research, company deep dives, AI engineering tips, & more