THEWHITEBOX

Could this be 2026’s big money move?

Last week, we had one of those “the world is ending” days for NVIDIA, which fell by almost 7% at one point. And while March’s debacle (the DeepSeek crash) was vastly exaggerated, this one is warranted.

In pure market style, now people think Google is eating NVIDIA’s lunch with its Tensor Processing Units (TPUs), their equivalent to GPUs. Finally, the market has realized that Google is serious about entering the AI hardware business.

But I want to give you the hard data so you can decide for yourself how large the risk is for NVIDIA. We’ll discuss:

What makes TPUs different,

A very deep analysis of the performance per dollar for each option, including why NVIDIA is directly lying to you,

And we’ll cover what I believe are the most important market insights going into 2026, such as NVIDIA's “secret weapon” markets don’t have on the radar yet, AMD’s last opportunity to join the party, and a secret player that might rise to prominence unexpectedly.

Whether you’re an investor or just an AI enthusiast, here's what to watch out for in 2026 in the most profitable business in AI: chips.

Save 55% on job-ready AI skills

Udacity empowers professionals to build in-demand skills through rigorous, project-based Nanodegree programs created with industry experts.

Our newest launch—the Generative AI Nanodegree program—teaches the full GenAI stack: LLM fine-tuning, prompt engineering, production RAG, multimodal workflows, and real observability. You’ll build production-ready, governed AI systems, not just demos. Enroll today.

For a limited time, our Black Friday sale is live, making this the ideal moment to invest in your growth. Learners use Udacity to accelerate promotions, transition careers, and stand out in a rapidly changing market. Get started today.

Years Later… Finally A Rival

The reason for NVIDIA’s fall was a report by The Information saying that Google, the new darling of AI stocks, was heavily pushing to sell its TPUs to customers, specifically mentioning Meta and Anthropic, crucial buyers for both NVIDIA and Google, as early adopters.

We covered both “exclusives” here weeks ago, as this was already “known” among more specialized analysts before The Information disclosed it.

Rather, The Information simply made accessible ‘common knowledge’ what we analysts knew way before (as the Spanish saying goes, it was “un secreto a voces”, a “secret” that wasn’t really a secret and was being shouted for anyone who actually knows how to follow this stuff to hear, like seeing Anthropic opening a TPU Kernel Engineer, as we discussed a few weeks ago).

Also, the fact that Anthropic’s Head of Compute, James Bradbury, is an ex-Google expert on TPUs and Jax (the software equivalent to NVIDIA’s CUDA), isn’t particularly bullish to NVIDIA either.

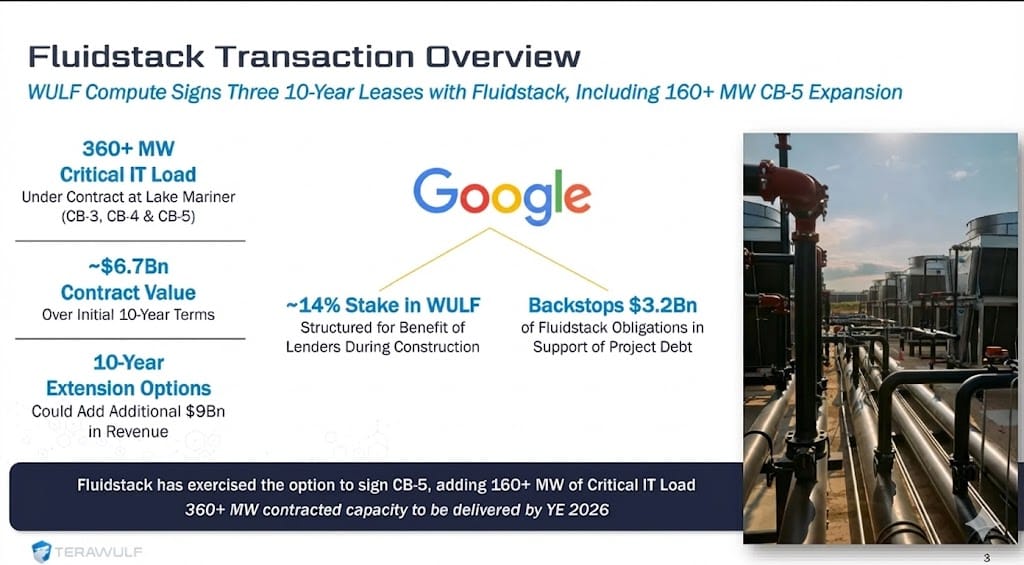

Furthermore, TeraWulf announced a deal with Fluidstack, in which Google acted as a backstop in case Fluidstack couldn’t pay rent to Wulf… just as Fluidstack was announcing its agreement with Anthropic.

Source: TeraWulf

All this goes to prove that markets aren’t remotely aware of what is going on until mainstream media catches on. But let’s get into the weeds to describe why this matters and why it is happening.

A Move to Challenge NVIDIA

The narrative for NVIDIA bearishness is dead simple: NVIDIA was “untouchable”, and it isn’t anymore, thanks to Google’s chips, the TPUs that not only gave “birth” to the widely considered best model around, Gemini 3 Pro (this is a speculative claim at best, but it’s nonetheless “common knowledge”), but they are also (alongside Amazon’s own ASIC, Trainium), behind Claude 4.5 Opus’s training.

Now, Google wants to sell these chips to third parties rather than just renting them, making it an official competitor to NVIDIA and AMD.

NVIDIA seems nervous enough that they published a statement, pumping their chests, saying that while they were congratulating Google, their GPUs were better. But the truth is, Google is serious about this.

But how serious? Google’s TPU business is real, and it looks pretty good.

As we’ll see today, I believe this is the last thing Google needed to become the world’s most valuable company, something I predicted would happen before the end of 2026… but might be coming much sooner.

My analysis of Google in my newsletter back in April (‘Why Google is your best AI bet’) was particularly timely. We highlighted its potential when it was at its lowest valuation of the year, even though we’ve been championing Google for almost two years at this point). But the market finally woke up and, from that point to today, the stock has risen by 118%, more than doubled.

Not that bad of a trade!

But let’s get to business. Why would anyone choose Google’s chips over NVIDIA’s? How good are TPUs when compared to NVIDIA’s GPUs?

The technical differences

From a technical standpoint, the fundamental differences between them are notable. The first question we must answer is what makes them different. Both are accelerators, meaning hardware specifically designed to accelerate computations. How, you ask? By parallelizing them.

Instead of executing a set of computations in sequence, we do many of them in parallel. Of course, this only works for workloads that are actually parallelizable.

In our case, both GPUs and TPUs focus on a particular type of maths, linear algebra, and in particular, matrix multiplications (‘matmuls’), which can be broken into parts and, thus, executed faster.

And here’s where the big difference between each product emerges. I’ll cut to the chase:

GPUs perform ‘tiling’, breaking down matrices into parts that are computed separately.

TPUs use systolic arrays, where both matrices being multiplied are sent through a ‘systolic array’ that reduces the number of timesteps required to compute the multiplication from 45 in the naive form to just 14 (for a 3-by-3 matmul).

Systolic arrays are complicated to draw, but this very short YouTube video explains brilliantly how this type of computation ‘accelerates’ matmuls and, thus, AI. It’s also important to note that a TPU is an ASIC (Application Specific Integrated Circuit), a chip designed for a particular task (in this case, AI).

Crucially, the other big characteristic difference is that TPUs require lower power, simply because they are meant for one thing and one thing only, while GPUs retain some of the original flexibility, making them less optimal for any given workload.

Technical clarification: The leading cause for higher power is higher clock rates, meaning a GPU does more operations per second (understanding operations as doing “stuff” than TPUs for the same number of effective math computations). That is, TPUs are more efficient for this particular math.

But theoretical efficiency and reduced power requirements are basically rounding errors in a game where capital costs govern the total cost of ownership (TCO).

In layman’s terms, in a market where buying the actual hardware accounts for 80% of the total cost of buying and using it over its entire lifetime, being a few hundred watts more efficient doesn’t cut it.

So, time to find out the answer. What option is, economically speaking, better?

Basics for the analysis

Before we proceed, the nitty-gritty. AI accelerators (i.e., AI hardware) are measured in “number crunching” capacity. That is, how many operations per second they can deliver.

This number is measured in FLOPs (Floating Operations Per Second), where a floating-point operation is a term for a number in scientific notation.

From decimal to floating

This is mostly irrelevant to understanding the rest of the article, so don’t worry too much about it. Fun fact, it’s the use of floating numbers the main cause for non-determinism in AI (the fact the outputs from neural networks like ChatGPT aren’t entirely predictable) due to their non-associative nature (i.e., (a + b) + c ≄ (a + c) + b). I talked about it here.

Therefore, the best way to compare both is to use metrics such as performance per dollar, particularly relative to TCO. In other words, how many operations on average are we going to get for every dollar we have paid and will pay?

Another critical thing to consider is that, in AI, we always, always look at system-level metrics. I won’t go as far as to say chip-level metrics are irrelevant, but let me put it this way:

If per-accelerator metrics were the vital thing to look at, AMD would be a $5 trillion company.

The reason is that AI workloads, both training and inference (running the AI models), are distributed, so we almost always require two or more accelerators per workload. This means the value customers are actually looking at is the metrics of your AI servers, not the performance of a single chip.

All things considered, to perform the economic comparison, we will compare both companies by TCO/TeraFLOP (one trillion operations per second) of compute using FP8 (the most common precision used in AI, where each number has 1 byte (or 8 bits).

The reason I mention precision is that it determines how many computations an accelerator can do per second.

For the analysis, we are going to compare Google and NVIDIA’s top servers, the Ironwood TPUv7 pod and the Blackwell Ultra, respectively.

The former has a scale-up of 9,216 TPUs, meaning each server has 9,216 individual TPUs. This is the largest AI server on the planet by far (careful, I said server, not cluster)

On the other hand, the Blackwell Ultra, or GB300 NVL72 server, has a scale-up of “just” 72 GPUs.

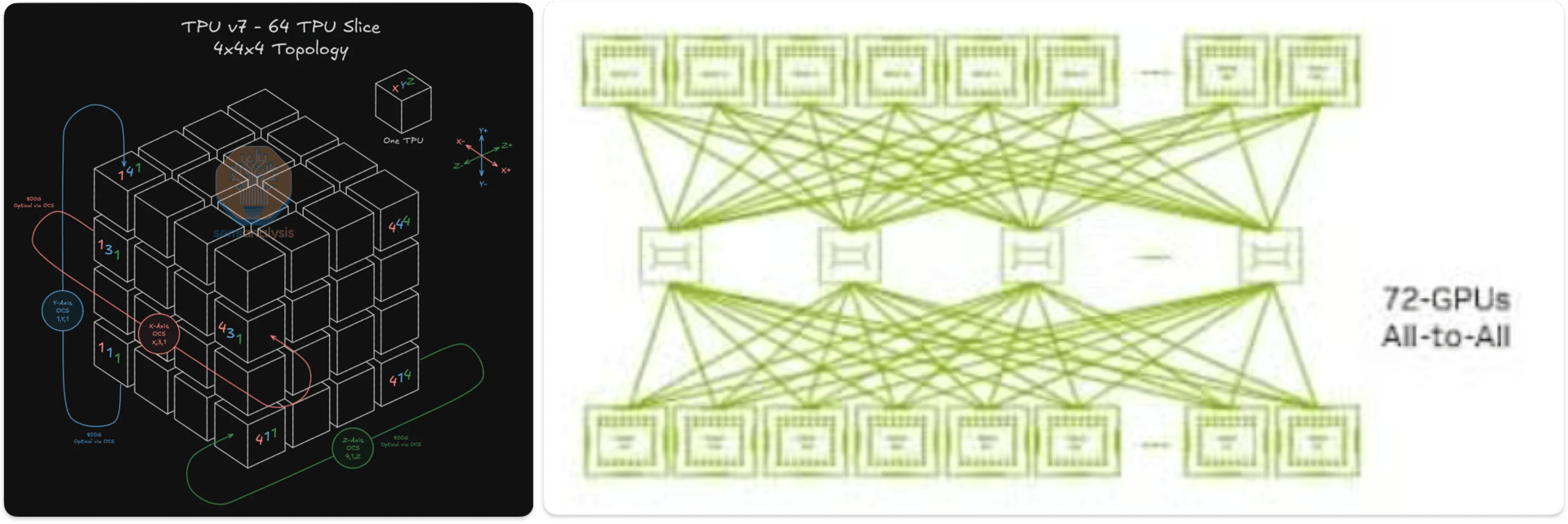

It’s important to note that this can be an “unfair” comparison because Google's larger pod is due to the server topology.

TPUs are distributed in 3D torus style. This means TPUs aren’t all connected directly to one another but in the form of cubes, where each small cube (a TPU) is directly connected to six other TPUs (one per face), and these TPUs are then structured in 64-strong TPU cubes (a physical TPU rack). Edge TPUs are connected to other edges, creating the ‘torus’ form.

On the other hand, NVIDIA’s topology is all-to-all, where each GPU is connected to every other GPU in the server directly. Luckily for us, we don’t have to worry about this because we’re looking at system-level metrics that already account for this.

Finally, we'll start with the analysis, then move to the ‘so what’ part, where I’ll share what I believe is clearly the outcome (winners and losers) for 2026.

A Clear Winner… Or Not?

To make this as accurate as possible, since we’ll be relying on estimates in some cases, I’m going to use two popular analyst sources instead of one and compare them. These are The Next Platform and SemiAnalysis, as well as my own estimates using Jensen Math (more on that later). One is “more right” than the other, but I still want to include it so that you’re aware of the variability.

Honest Cost Comparison. Who’s Cheaper?

According to the semiconductor expert blog The Next Platform, they estimate a 9,216-TPU Ironwood pod, the largest scale-up size Google offers for its latest TPU generation (i.e., how many TPUs can they scale a single system to), costs $445 million to build (including all costs, not just the chips themselves). Assuming a 20% markup (my estimate), that gives us a retail price of $534 million.

This system has a theoretical FLOP throughput of 42.52 ExaFLOPs (official, published by Google). That is, the pod can deliver 42 quintillion operations per second.

This gives us a build cost of $12.56 per TeraFLOP for the Google Ironwood cluster.

On the other hand, an NVIDIA GB300 NVL72 (72 GPUs), the so-called Blackwell Ultra, has an unknown retail price and offers a peak throughput of 0.72 ExaFLOPs, or 59 times less than Google’s system.

Luckily for us, Jensen Huang, NVIDIA’s CEO, was happy to share the numbers we can use as guidance. On one occasion, Jensen mentioned that the capital cost of 1 GW was around $50 billion to $60 billion, of which approximately $35 billion was going directly to NVIDIA in direct GB300 value.

Assuming $55 billion for 1 GW in NVIDIA server equivalents and using Schneider Electric’s 142 kW per-rack form factor (meaning it’s a GB300 NVL72 built by Schneider requiring that much power), this would mean around 7,142 GB300 servers, or $4.9 million per rack of GPU direct investment, and around $7.7 million per rack once counting all data center costs.

Supply chain clarification: NVIDIA designs the chip, but it’s up to the OEM (Original Equipment Manufacturers), companies like Dell, Schneider Electric, or Oracle, to use the chips manufactured and packaged by TSMC and, with the platform guidance from the ODMs (Original Design Manufacturers) like Foxconn or Quanta, to build the actual AI servers deployed in data centers.

Thus, on a very rough comparison estimate, the resulting values are:

NVIDIA’s GB300 NVL72: $4.9 million / (0.72 ExaFLOPs) = $6.81/TFLOP

Google Ironwood PoD: $534 million / (42.52 ExaFLOPs) = $12.56/TFLOP

All in all, even though we are talking just about capital costs, they represent the overwhelming majority of the TCO, so it seems costs look clearly better from the NVIDIA perspective.

But wait, weren’t TPUs cheaper? Why would anyone even consider TPUs then?

Well, let me put it this way: the analysis is incomplete because NVIDIA is lying to you.

Under the paywall, we’ll answer the following: the “tricks” NVIDIA plays on us; the role Broadcom plays in all of this and what to make of it as an investor; the outlook for the big three, NVIDIA, Google, & AMD; the picture once considering NVIDIA’s newer GPU, Vera Rubin, Google’s upcoming TPU, TPUv8, and AMD’s MI450; and the takeaways to navigate AI hardware in 2026, the most dynamic market in the space, with key events to watch out for.

Subscribe to Full Premium package to read the rest.

Become a paying subscriber of Full Premium package to get access to this post and other subscriber-only content.

UpgradeA subscription gets you:

- NO ADS

- An additional insights email on Tuesdays

- Gain access to TheWhiteBox's knowledge base to access four times more content than the free version on markets, cutting-edge research, company deep dives, AI engineering tips, & more