Your daily AI dose

Mindstream is the HubSpot Media Network’s hottest new property. Stay on top of AI, learn how to apply it… and actually enjoy reading. Imagine that.

Our small team of actual humans spends their whole day creating a newsletter that’s loved by over 150,000 readers. Why not give us a try?

FUTURE

Will AI Take Your Job, and When?

With the release of Deep Research tools by the likes of OpenAI, Google, and most recently, Perplexity (cheapest option by far and reasonably well tested against the others), concerns about job safety and displacement due to AI are growing.

But we know history repeats, so does history support these fears? And if so, what skills will be necessary to survive in an AI world?

Today:

We’ll discuss the impact timelines previous industrial revolutions had on the economy, discussing important milestones and the Baumol effect.

We’ll examine the most recent research on adoption and productivity from one top University and one top AI lab, showcasing how adoption is never what it seems.

We’ll understand what it means to be an ‘AI Human.’ Just as the world saw the rise of the Renaissance man in the 15th century, we will cover the essential skills of the AI human, a person who, be it an employee or an entrepreneur, embraces AI and thrives above everyone else.

Finally, I will give you the best mental model to analyze whether AI will take your job. And let me tell you, every single person around you is approaching this question wrong.

Let’s dive in.

A Brief History Review

AI is considered the next industrial revolution. But what does that even mean?

Change Takes Time.

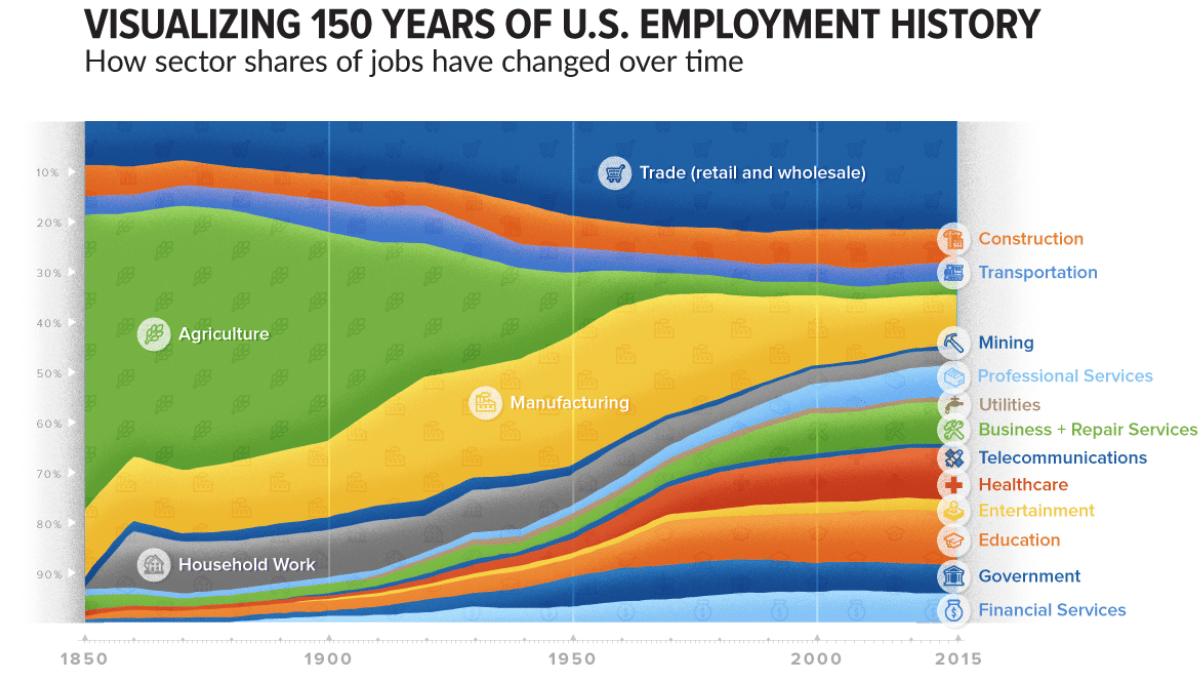

Back in 1820, agriculture was the dominant occupation in the United States (and in most countries), with an aggregate presence of 72% over total gainful work.

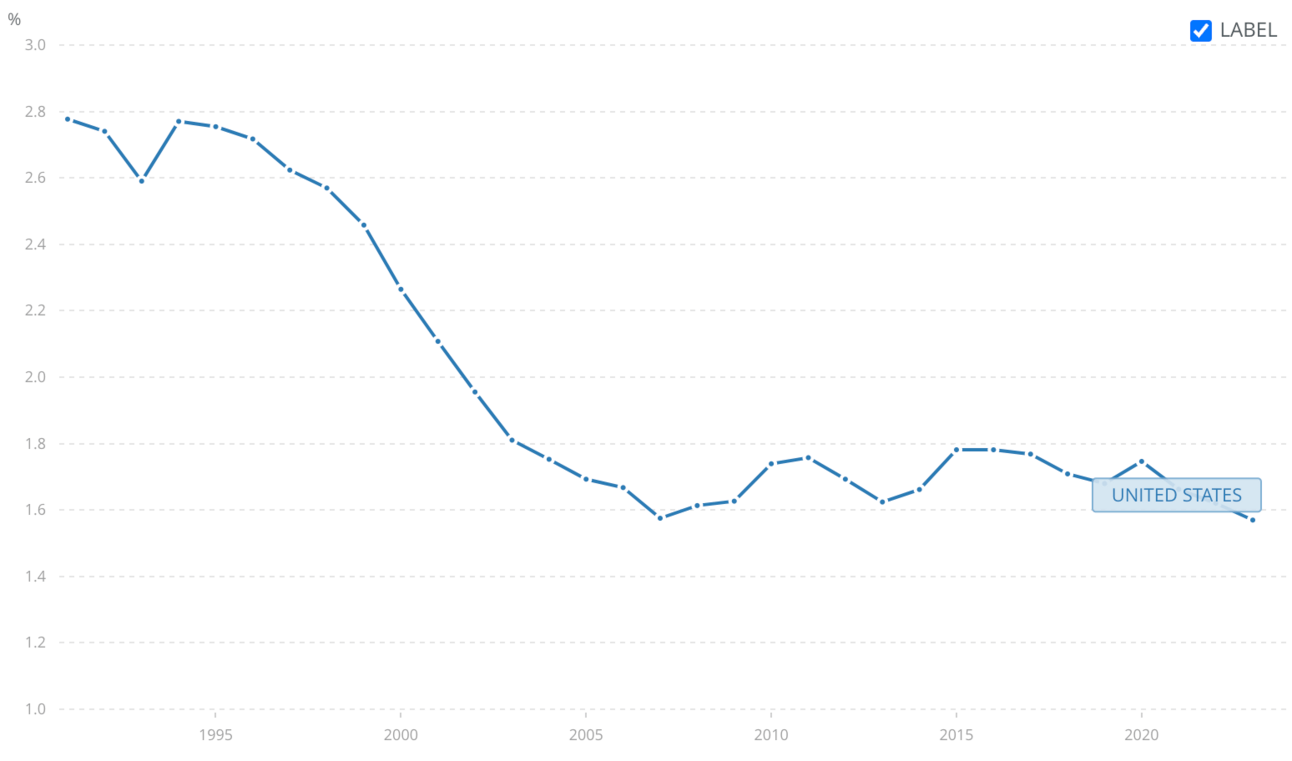

Today, that value has dropped below 2% in the US, with most developed countries below the 5% mark (the global average is still high, at 26%)

But why? The answer was mechanization. Better farm equipment and the advent of steam power led to a series of productivity improvements, like the mechanical reaper of the steel plow (1831 and 37, respectively).

Over time, the growing use of railroads and transportation of crops to distant markets shifted farming from subsistence to commercial. This led to a shift in jobs, from railroad to other forms of manufacturing, the former of which represented 10% of UK labor by 1850. This, led by the advent of coal, led to a gradual transition toward these new jobs, and while agriculture remained the main job source for the rest of the 19th century, by 1900, it had gone down to 40%, while industry rose to 26%.

Of course, all this change severely impacted some, such as weavers, who saw a 65% decline in wages (despite a 400% increase in textile output).

Yes, some jobs were displaced, and McKinsey predicts 12 million job displacements by the end of the decade in the US alone due to AI. But which, and when?

That said, to summarize, because I don’t want to bore you with too much history, the key insight is that:

Change took time. Decades, in fact, so why would AI be any different?

To answer this, were other industrial revolutions more sudden?

Change Takes Time.

Another big change came with the next great phase of the industrial revolution, during the periods of 1870 and 1914. The first commercial power plant, a key driver of progress during the 20th century (and still today, as energy is seriously bottlenecking AI progress), appeared in 1882, Edison’s Pearl Street Station.

However, it took four decades, 1920 to be exact, for electricity to surpass steam as the dominant source of horsepower. Did humans take 40 years to realize electricity was better? No, but as I was saying:

Change takes time.

But we have even more recent examples. The microprocessor was created in 1971, but twenty years later, only 20 million PCs were sold globally yearly (that number is 255 million today).

All things considered, while some people saw huge change rapidly at the microeconomic level, the overall impact of these changes in the economy took time. Yes, some jobs simply disappeared, just like motor vehicles killed carriage coaches, but from a macroeconomic perspective, the effect of these technological shifts was steady but slow.

For instance, according to Professor Nicholas Crafts, the steam engine contributed 0.2% per year to productivity growth for 20 years and then 0.38% per year for another 20 years in the mid-19th century.

Regarding AI, projections have been made too, and people like MIT professor Daron Acemoglu suggest that AI’s impact on total productivity will be just 0.66% over the next 10 years, which appears to be very low but is consistent to what history has shown.

But, wait, if the microeconomic impact seems so massive (huge job displacement in many jobs, considerable improvements in task productivity across the board, etc.),

Why is the macroeconomic impact so small, and why does it take so much time?

Productivity and the Baumol Effect

No one can deny that, when used well, AI leads to significant productivity improvements. In such sectors, AI will raise wages and skyrocket throughput per worker.

But how does that affect GDP?

One reason to suggest why macroeconomic impacts take so long to be visualized is that sectors seeing huge productivity improvements will generally lose a ‘share’ in the GDP pie graph, as each sector’s impact on GDP is measured as {price x quantity}. While quantity skyrockets, demand grows (Jevons Paradox), but productivity and competition lead to substantial price deflations that generally outpace the increase in quantity (aka, price falls more than quantity grows, so the total output of that sector falls).

This explains why agriculture’s share in GDP, while falling tremendously, has not implied starvation. In fact, we have produced as much food as ever in history (4 million metric tons a year), yet its price has fallen so much that its net GDP output is small.

In the US, agriculture used to account for 90% of GDP. Since, it has shrunk to just 0.8%.

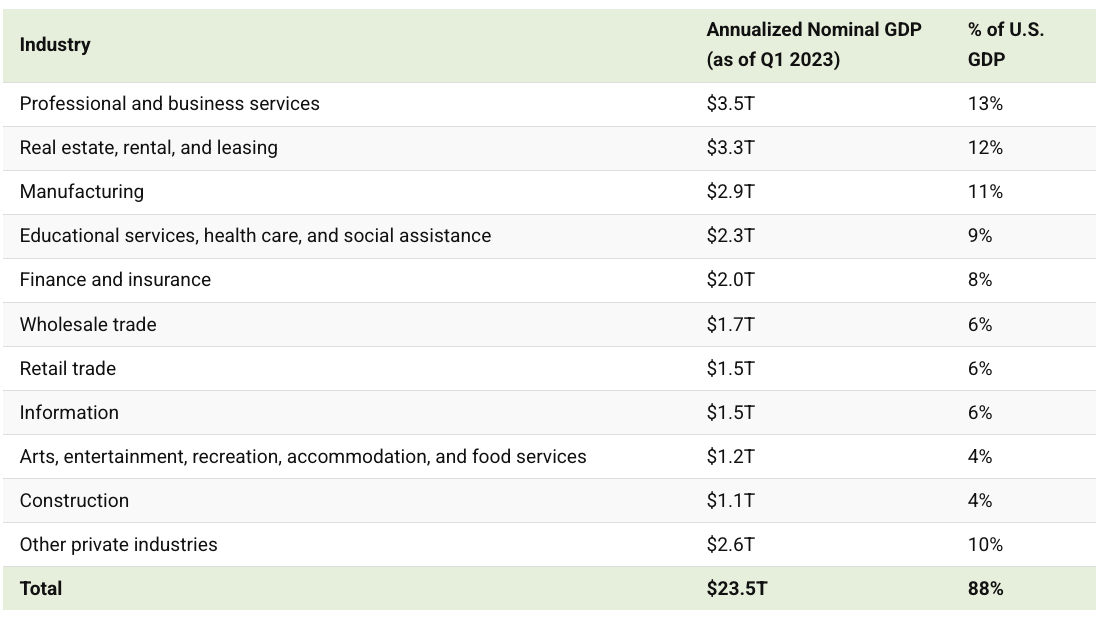

Consequently, this leads to GDP being concentrated in low-productivity sectors, like professional services, housing, or education, with very low automation potential:

But does that mean that GDP becomes insensitive to those increases in productivity? No.

As described as the Baumol effect, the rise in wages in highly productive sectors leads to the increase of wages in low-productivity sectors. This causes the Baumol cost disease, where costs in low-productivity sectors grow despite their low productivity in response to higher wages offered in other sectors (making them more attractive for workers in low-productivity sectors, which causes wages to rise in response), further decreasing the efficiency of those sectors despite total GDP output increasing (as wages and spend increase).

Again, this naturally leads to GDP concentration in low-productivity sectors. So, what can we take away from all this?

In my humble opinion, analyzing AI’s impact on GDP is pointless until it can seriously dent manual labor-intensive sectors. AI’s real impact on GDP (Baumol effect aside) will only come once we achieve full embodiment (robotics) so that low-productivity sectors are also impacted.

Until then, AI's impact will concentrate on digital sectors, also known as knowledge work. But the question is, is knowledge work already seeing such impact?

And the answer is, well, it depends on who you are.

AI Impact is not About the How, But the Who

Over the last few weeks, two very interesting pieces of research have emerged, one coming from a top AI lab that shows how data and narrative don’t always go together, and one coming from Stanford. The latter focuses on Generative AI’s effect on productivity, and the former focuses on the fundamental question:

Is all this happening already?

A Net Time-Saver

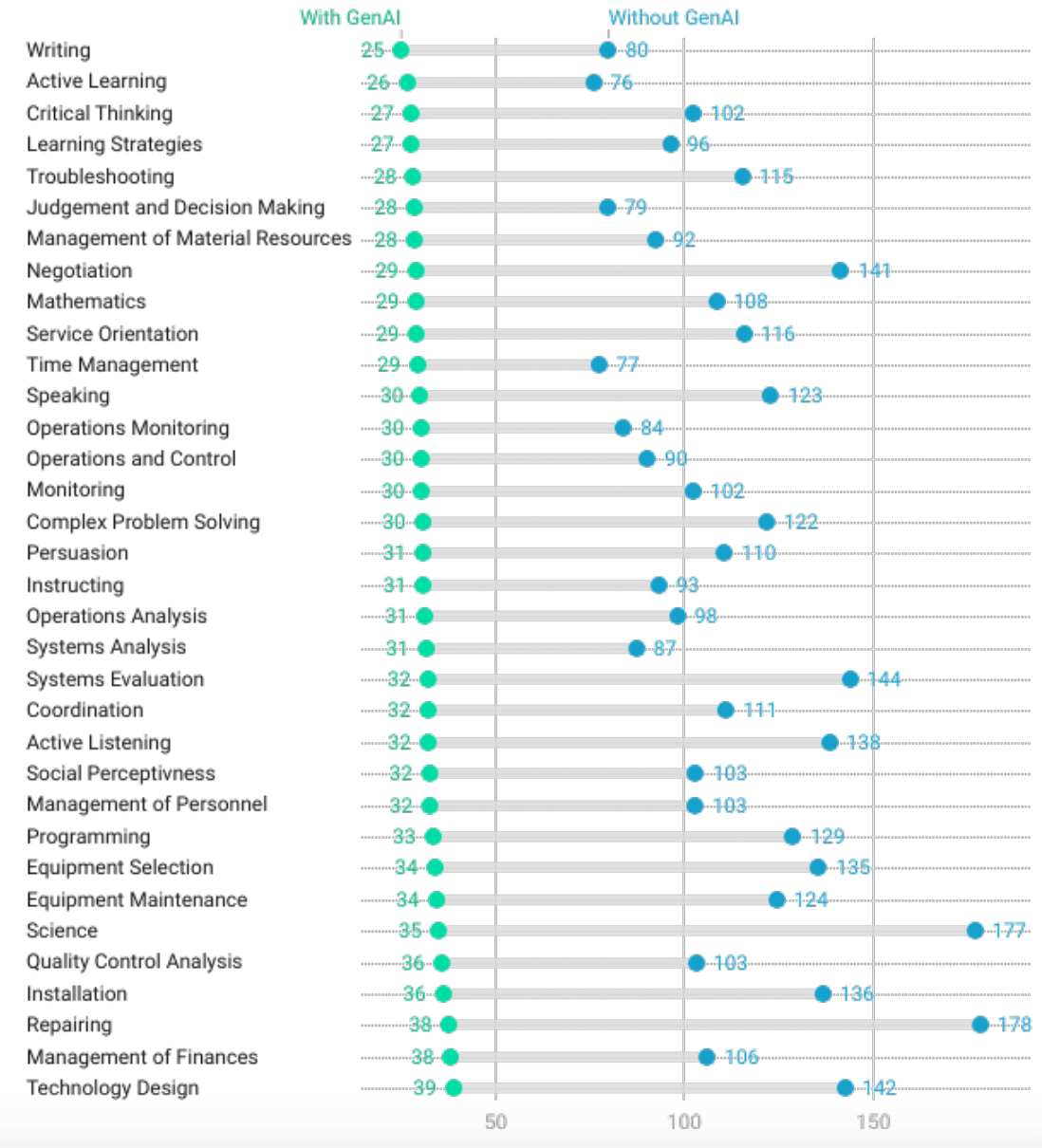

Regarding Stanford’s research, they conclude a set of interesting insights:

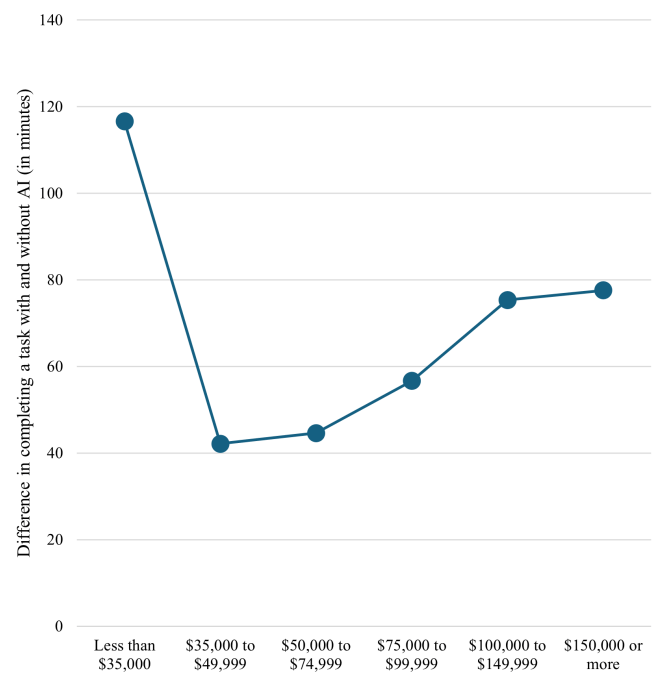

In all measured tasks, Generative AI represents a net improvement in productivity measured by time to completion, in some cases representing more than a 400% time decrease:

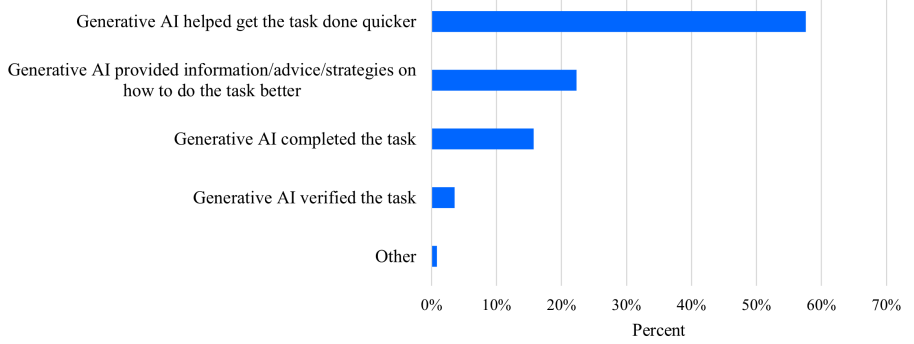

With time savings consistently being chosen as the main driver for model use:

This ‘time-saving’ pattern was common across all wage classes, with most people acknowledging its use at least five days a week.

These are pretty strong numbers that suggest that AI as a productivity tool is well underway. So why aren’t we seeing media panic, massive job displacements, net price deflation, or improved supply?

And, crucially, why aren’t AI incumbents’ revenues soaring? And the answer, as pointed out by a frontier research lab last week, is that things are not what they seem.

Subscribe to Full Premium package to read the rest.

Become a paying subscriber of Full Premium package to get access to this post and other subscriber-only content.

UpgradeA subscription gets you:

- NO ADS

- An additional insights email on Tuesdays

- Gain access to TheWhiteBox's knowledge base to access four times more content than the free version on markets, cutting-edge research, company deep dives, AI engineering tips, & more