THEWHITEBOX

What Will AI Look Like in 2026? The New Frontier

2026 is the year of the “world model”. You’re going to hear those two words uttered by every AI hyper on the planet over and over again.

But by the end of this article, you are going to be ready for them.

The writing is on the wall. AI Leaders like Demis Hassabis, Yann LeCun, or OpenAI’s Sora creator Bill Peebles can’t stop talking about this inevitable transition from LLMs to world models. Even Elon is jumping ship on this.

But what really is this world model thing? To answer, we aren’t going to respond like someone who pretends to know the answer. We are diving deep; we are going to derive what a world model is, to detail what might be frightening at first, but required to grok the idea fully.

In particular, we will:

Understand what the theoretical perfect AI model is, based on things like compression, Solomonoff induction, Bayesian Inference, and Shannon’s entropy,

Explain how LLMs are just a “best effort” approximation of this, but with serious limitations,

And unpack it all up by defining what AI models will look like in 2026, based on the words of Demis Hassabis himself, and what industries should see a big jump if AI Labs are successful.

Today, we are tackling several dense concepts at once, which can be hard to follow.

To tighten things up, besides using several visual representations to clarify complicated concepts, we will traverse these challenging concepts by “building” what is today the most advanced world model ever: Google’s Waymo autonomous driving system. In other words, we are going to see how each of these, combined, takes you from the basics of AI to the most advanced AI embodied system the world has ever seen.

I’ve wanted to write this article for years, but I never felt ready. Now I think I am. Let’s dive in.

The Importance of World Models

To get to world models, we must first understand what is the perfect AI model, how LLMs aren’t even close to that view, and how world models might be the endgame.

And to begin this journey, we start with the foundation.

The role of compression

The role of any AI model is to predict future data; that’s literally all they do. The question here is how you build such a model. And by far the most prevalent way is through compression.

The idea is simple: expose an algorithmic compressor, usually an artificial neural network (ANN), to large amounts of data and have it predict it.

The intuition is to have the model make predictions by performing induction, moving from the specific to the general, deriving general rules by seeing loads of examples, like learning to predict a verb after “I” just because every time it sees “I”, a verb comes next.

This is the opposite of deductive reasoning (from the general to the specific), which is how humans usually learn to speak or write through the principles of grammar (e.g., “Every time you see ‘I’, a verb should come next).

Either way, once the model finds a general rule, it no longer has to consider the possibility that, after “I”, comes an adjective, even if it’s something that a word model like ChatGPT could theoretically predict.

This is what we describe as compression: picking up patterns in data (usually referred to as ‘regularities’), discarding faulty predictions and overall noise, and focusing on what matters.

In our journey to building Waymo’s autonomous driving system, compression helps us ignore the noise. Imagine we’re driving into a messy city intersection. The sensors produce a firehose of raw data, but the car can’t “remember pixels”; it must compress reality into the few regularities that matter for prediction: lanes, objects, motion, and right-of-way.

But how do you build such a compressor?

Neural Net 101

I’m going to keep it short. At this point, everything in AI is a neural network.

Out of all the options we had, we consistently chose the same one, over and over, until the entire industry is “one fat neural network”.

A neural network, no matter its shape and form, is just a pattern compressor, a huge mathematical function that maps inputs to predictions.

Input: house data. Output: Prize prediction (Zillow’s faulty AI)

Input: brain signals. Output: Thought prediction (Neuralink)

Input: words. Output: The next one (ChatGPT)

Input: Breast x-ray. Output: Tumor, yes or no.

You get the point. And all of the above are neural networks, functions that take in an input and predict an output (F(input) = output), and have been trained by seeing sometimes trillions of input/output pairs, to the point that the model figures out what structures (regularities, or patterns) in the input give a specific output.

However, these functions have a particular trait: they are probabilistic, meaning the model not only decides on a given output but also assigns a certainty value in the form of a probability.

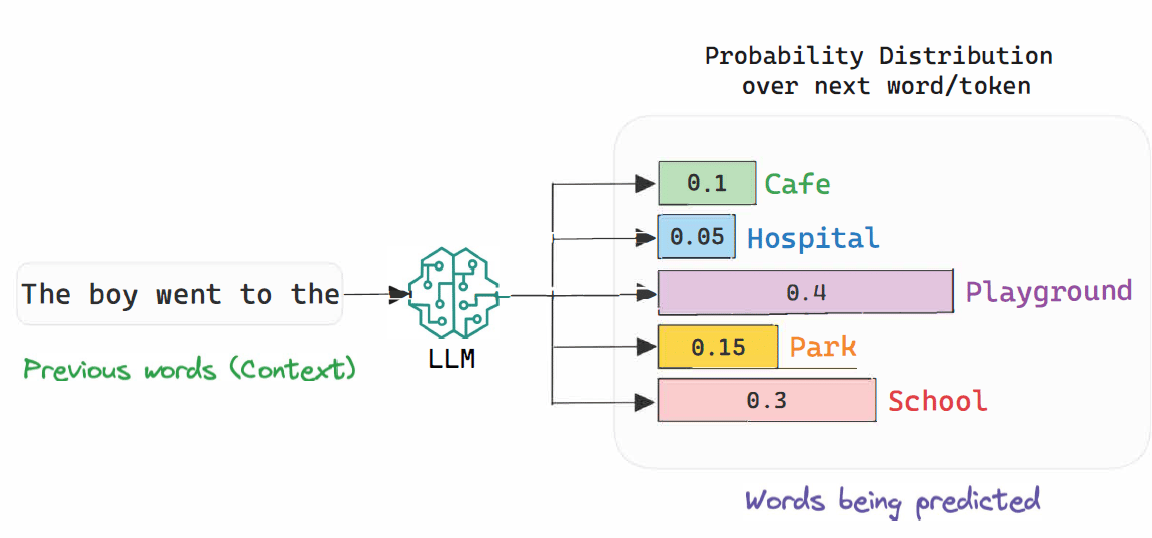

The perfect example is ChatGPT, which takes in a series of words and returns a huge list of all the words it knows, ranked by likelihood of being the next one.

This is called a probability distribution, which means models, in many modern AI systems, usually output a probability distribution (especially for classification and generation) instead of a single value.

One of the reasons models predict probability distributions is to prevent model “mode collapse”. The perfect example is ChatGPT. Recall that neural nets learn by induction, seeing a lot of data to figure out the common patterns. This makes them highly frequency-biased, meaning the more they see something, the more likely they are to predict it.

But the English language is very diverse, meaning there are multiple ways of saying something, of expressing an opinion or a thought. Therefore, if you force a model to pick only one option every time, it will “compress its way” into the mode of the distribution, always providing the same answers.

Instead, by letting it consider multiple options in its response and simply applying certainty values to each, you get a more varied set of output answers.

Source: Generated by the author using Gemini 3 Pro Image (nano banana pro)

To incentivize even more “creativity,” we add randomness to the sampling, meaning most LLMs pick up one of the most probable outcomes, not the most probable by default.

But how does this help us in creating our self-driving car system?

Recalling our example of a car driving into a messy intersection, we might have missed a parked van that could hide a pedestrian. A good model shouldn’t commit to one possible explanation; it should output a probability distribution over possibilities, because driving is primarily acting under uncertainty.

But are LLMs the perfect compressors?

Not even close, they are approximations (in the words of Ilya Sutskever, one of the fathers of modern AI) of what we know as Solomonoff Induction, the theoretical perfect universal predictor.

But what is that?

The best possible predictor and Bayes’ Theorem

At this point, I hope that it’s clear by now that AI = predictor. But what makes the perfect predictor? Most researchers will point you to the Solomonoff inductor.

Interestingly, this theoretical model is not a model, but a distribution of models or programs. For a given question, a Turing machine samples these models proportional to their length (here, the inductive bias, the assumption the system makes, is that shorter programs are better, also known as Occam’s Razor).

Each model is tested to see whether it can solve the problem, and those that solve it are ‘reweighted’ so that, in the next round, they are more likely to be chosen.

Over time (infinite time, that’s why it represents the theoretical upper bound), the system will collapse to the most general models, those that predict the most data well.

The crucial thing here is how we update the weights for each model (the likelihood that each model is chosen). The answer is Bayes’ Theorem, one of the most influential yet misunderstood formulas discovered by humans. Let’s understand this with an example.

Say you’re feeling really bad. You take a bunch of tests, and you test positive for an illness that only 0.1% of the population actually has. The test that you tested positive for has a 99% accuracy, meaning it will correctly identify positives and negatives 99% of the time.

How likely is it that I have it? Your immediate reaction is probably to think “99%”. Well, luckily for you, no, because the actual answer is ~9%.

But how? This is what we call the Bayesian trap, because we aren’t considering a crucial concept called evidence.

Don’t be too harsh on yourself if you immediately thought 99%, because everyone makes this mistake including, to the my utmost concern, most doctors.

But how?

And the answer is that you have to look at the evidence. The probability we want to find is not P(I have the illness), which is what most people think in this case, but P(I have the illness given I tested positive). That is, we are talking about conditional probabilities here, my dear reader.

This introduces us to Bayes’ Theorem, shown below, an equation that lets us compute conditional probabilities given:

P(testing positive given I have the illness), called the likelihood (the probability of testing positive given that you have the illness), denoted P(B|A) below,

Previous knowledge (the prevalence of the illness itself), denoted P(A) below,

and the evidence, the total probability of testing positive, denoted P(B) below.

In our equation above, we want to measure P(A|B), or what is the probability ‘A’ that I have the disease, given the event ‘B’, that I tested positive for.

But imagining probabilities is hard enough in frequentist statistics, so dealing with conditional probabilities is even less intuitive. Thus, I always recommend drawing a probability tree, as the one below, from a given sample, say 1,000 people.

The probability that any one of these people has it is 0.1%, so exactly one person out of every 1,000 has it (whether or not any tests are performed; this is just the disease’s prevalence).

That means 999 don’t actually have it. However, our test isn’t perfect (99% accuracy), so 1% of these will be marked as positive even though they aren't true positives (this is called a false positive). This gives us 9.99 people will test positive despite not being ill, and 989 will test negative while being real negatives.

For the lonely dude who sadly has the disease, 0.99 of these people will be marked as positive (true positive), and 0.01 won’t—I know fathoming the idea of ‘0.01 human’ is weird, but bear with me.

Now, let’s move these numbers into probabilities again. So, if we plug all this into Bayes’ Formula, we have:

Source: Author

And what does this have to do with the perfect universal predictor?

Simple: in the event we could consider all possibilities, all possible models to explain the data (to predict it), we would use Bayes’ rule to update the distribution of models (reweighting so that better models are more likely to be chosen), so that our predictions are always updated to the latest evidence.

Solomonoff’s universal predictor is perfect because it handles uncertainty perfectly; no matter how weird the new data is, we are guaranteed to find the model that predicts it better, and we can use Bayes’ Theorem to update our beliefs and thus make better models of the world more likely to be chosen.

But as you can guess, Solomonoff’s universal predictor would require infinite computing to run, which is not possible.

Circling back to a self-driving system, this theoretical ideal would consider every possible explanation for the sensor stream (every “program” describing physics and behavior), and then update its beliefs as evidence arrives. That’s the intuition behind Solomonoff induction: a perfect-but-uncomputable universal predictor.

So, researchers realized: if we can’t run a Solomonoff predictor that is guaranteed to give us the best model over time, why not try to find the best possible model for all data?

And that, my friend, is the Large Language Model (LLM), our best possible try at this very particular problem, as acknowledged by Ilya Sutskever himself.

But to understand LLMs, we’re still missing one more piece. And for this, we have to go back in time again, this time almost 80 years ago.

Building LLMs through Shannon’s entropy

You wouldn’t be wrong if you said that modern AI is anything but modern.

At least, the theoretical foundation of LLMs is anything but new. Besides neural networks, whose principles are several decades old, the way we actually train the LLM can be traced back even further.

To train LLMs, we use a technique called MLE (Maximum Likelihood Estimation), which finds the model that maximizes the likelihood of generating the data being fitted to.

It’s asking: what is the best possible model that represents the data and best predicts it?

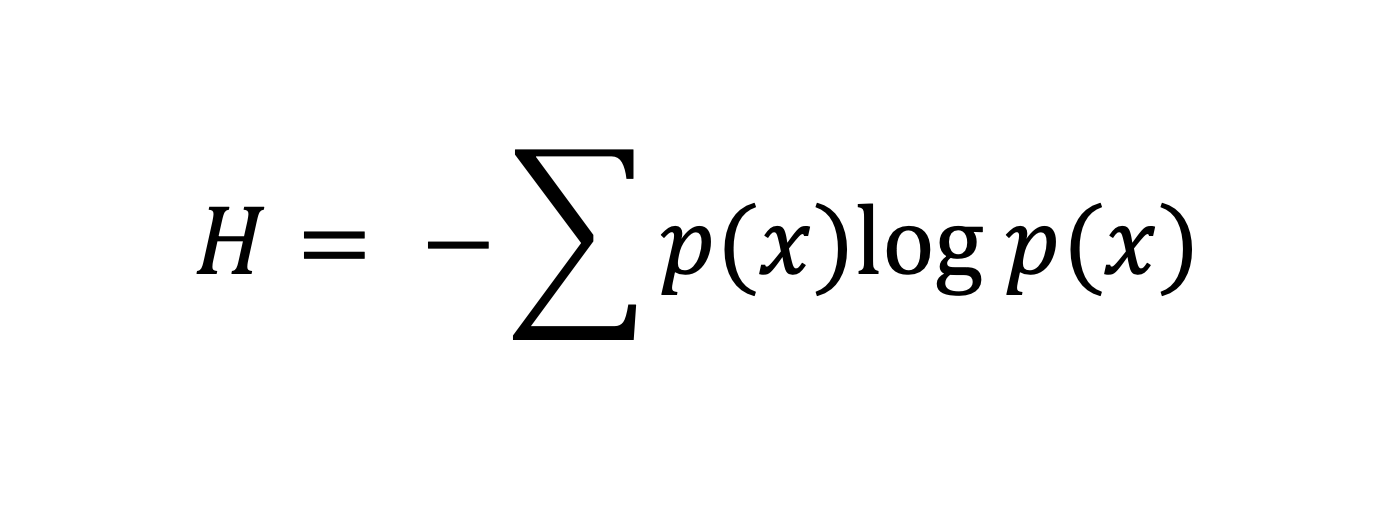

The formula is conceptually very similar, or basically identical, to Shannon’s entropy; training minimizes cross-entropy (average surprise under the model), which is equivalent to maximizing likelihood. This formula measures the amount of surprise (formally known as ‘surprisal’) an event has, measured by entropy (here, entropy means the amount of information a given event gives to you).

Entropy is context-specific (seeing dirt on the floor is surprising if you’re at home, not surprising if you’re in your garden), and is a mathematical way of measuring information.

But how do we measure surprise? It’s quite simple, actually; it’s the logarithm of the probability of that event according to the model’s predictions. We can intuitively think of this simply by drawing the logarithm on a graph.

As you can see below, the smaller the probability the model gives to an event, the more negative its value is. Conversely, the closer we get to 1 (100% certainty), the closer we get to 0, which makes sense because if the model is assigning an event close to 100% certainty, the “level of surprise” is close to 0.

We add the negative term shown above to convert the negative values to positive ones. Therefore, if we treat this as a loss, it implies that lower certainty leads to higher losses, and we tune the model to take probabilities closer to one (approaching zero, and thus, low loss).

And the probability of multiplying the logarithm? We add this to handle the prevalence of that event.

The factor p(x) is the weighting that says outcomes that happen often should contribute proportionally more to what’s “typical” than outcomes that seldom happen.

So, intuitively, Shannon’s formula gives us the entropy of an event by multiplying its probability of occurring by how surprising that event is. Of course, the more common an outcome is, the less surprising it is, and vice versa.

And why am I telling you this? Simple, because you’ve just “discovered” how an LLM is trained.

In practice, the objective function, the function we use to measure whether an LLM’s predictions are accurate, is a variation of Shannon’s entropy called cross-entropy, where we compare the model’s probabilities ‘q’ to a target distribution ‘p’. That is, we are “pulling our model towards” the data.

Intuitively, we compare the probabilities that the model assigns to the correct next word in the sequence with the likelihood of the ground truth (which is always 1, or 100%, naturally, as it’s the ground truth).

Thus, we are basically comparing every prediction the model makes (every next word, as we’re talking about LLMs) to the target distribution, aka the data, aka the exact word that was really coming next.

For instance, say we have the sequence “The sun is a…”. The ground truth answer is “star”, which has a 100% probability in the target distribution (the data we are learning from). If the model assigns a 90% certainty to “star,” that means the model was quite close. If it gave it a 20%, it was very, very far. This ‘gap’ is the learning signal we use to refine a neural network.

However, we must add another slight nuance to this formula, as our probabilities here are conditional, meaning our model is basically this: P(y|x), which translates to the probability of the output ‘y ’, given the input ‘x’.

We then usually choose the prediction corresponding to the most likely outcome, denoted argmax(P(y|x)), the highest value in the list of potential probabilities.

So, yeah, “modern AI” is training models using architectures that trace back to the 1950s (the multi-layer perceptron), with a formula from 1947, and using an optimization algorithm, gradient descent, defined back in… 1847. Not kidding.

But then, why aren’t AI models 150 years old? And the answer goes back the computability of induction.

For these models to work, you need mountains of data (going from the specific to the general needs a lot of data), and to process such data sizes, you need a lot of compute. The 2010s brought us GPUs with enough compute power to process large amounts of data, leading to the world we live in today.

Looking back again at our self-driving system, if we wanted to use an LLM as part of the system (in fact, that’s exactly what happens with Waymo’s vehicles), we would approximate this by training a neural net to assign high probability to what actually happens next in recorded driving data (next action, next observation, or both).

Thus, cross-entropy is “penalizing the model when it’s surprised by the real next step,” until it compresses the best driving distribution.

But then, if we now have models that can predict and handle uncertainty, do we have perfect models? Are LLMs world models? Are LLMs enough for our self-driving system?

No, we are missing one more thing: a state.

The dream of active inference

A prevalent theory of the human brain is what we know as active inference, meaning our brain behaves similarly to a Bayesian predictor, which is, by the way, also the holy grail of AI models.

Subscribe to Full Premium package to read the rest.

Become a paying subscriber of Full Premium package to get access to this post and other subscriber-only content.

UpgradeA subscription gets you:

- NO ADS

- An additional insights email on Tuesdays

- Gain access to TheWhiteBox's knowledge base to access four times more content than the free version on markets, cutting-edge research, company deep dives, AI engineering tips, & more