Want to get the most out of ChatGPT?

ChatGPT is a superpower if you know how to use it correctly.

Discover how HubSpot's guide to AI can elevate both your productivity and creativity to get more things done.

Learn to automate tasks, enhance decision-making, and foster innovation with the power of AI.

THEWHITEBOX

History is About to Repeat Itself

If there’s an argument being used against AI being a bubble, that’s the phrase “AI is not like the previous technologies.” But as legendary investor Sir John Templeton once said, “the four most expensive words in the English language are: this time it’s different.“

And the truth is, investors are so blinded by the AI craze that they aren’t making even a remote effort to look back in history to assess the similarities between the current state of the market and previous bubbles.

But what if I told you that, decades ago, this was the exact way investors were behaving, and the results were catastrophic?

Luckily, if you put in the effort, it’s clear which metric will define whether the bubble pops. Beyond that, we can also use the lessons from history to know how the pop will play out.

Today, we are answering just that. Because the truth is, we don’t need the bubble to be real; we just need enough investors to believe it is.

Let’s dive in.

History doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes.

Mark Twain knew what he was talking about more than 100 years ago, in that history tends to repeat itself. But as another legendary investor like Warren Buffett once said: “What we learn from history is that people don’t learn from history.”

So in the spirit of Buffett’s warning, let’s look at history to understand better what is going on today.

Because if you think we are in a unique market, boy, are you wrong.

Is there a bubble?

“There is nothing new on Wall Street. There can’t be because speculation is as old as the hills. Whatever happens in the stock market today has happened before and will happen again.”

People these days can’t stop talking about the AI bubble. The idea is running too deep already, to the point that institutions like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the Bank of England have both basically confirmed its existence.

Perhaps even more surprisingly, incumbents like Jeff Bezos and Sam Altman have both shared the view that we're in a bubble, arguing that people are essentially investing in terrible ideas (Bezos) and that an extraordinary amount of money will be lost (Altman).

But what is a bubble, really? It’s hard to say because definitions of a bubble are like opinions; everyone has one.

Bubbles are often defined from the perspective of valuations; if stocks appear very expensive relative to their earnings, we just assume they are bubbly. But there is no hard threshold that determines if a stock, or an index, is in a bubble, so this is kind of a flawed metric that is heavily shaped by your own narrative you want to base the analysis on.

And while It’s hard to disagree companies like Palantir or Tesla, both with prices well over 200 times their earnings (PE ratio > 200, meaning people are valuing the company at 200 times its current profits), are in a bubble, other companies usually mentioned in this discussions, like NVIDIA, offer a much more nuanced picture, despite being a 4.5 trillion dollar company at the time of writing this.

The most common metric to evaluate how ‘pricey’ a stock is is the price-to-earnings ratio (PE ratio), the multiple over profits the company has. NVIDIA’s current PE is 50, which sounds high historically, but its forward PE (its price assuming future revenue projections materialize) drops to 29, which is not an extraordinary valuation at all.

Thus, it may be expensive now, but it is acceptably priced relative to future profits. As markets are always looking into the future, many will conclude that NVIDIA is not in a bubble.

But as I was saying, when conversations center around valuations, it’s just a matter of narrative. If you want to convince yourself that NVIDIA is in a bubble, you can, and if you want to convince yourself otherwise, you can easily do so, too.

Instead, I prefer looking at the psychological side of things. Not about the stocks, but about investor behavior. While we will see plenty of insightful data points today, the key is not about the price people are paying for stocks, but their reasons for it.

And this is the biggest lesson I’ve learned from studying for this piece: people keep looking at valuations to draw analogies with previous bubbles like the dot-com, when it’s the behavior of current investors that actually pulls the ‘AI bubble’ eerily closer to another, much less known bubble, one that “killed” the market for almost a decade, and might give us the key to what will happen this time and how to prepare.

But in the spirit of being analytical, let’s compare today’s market to history along the lines of bubble type, market concentration, valuations, macro data, and geopolitics.

Bubble type

The biggest argument against the AI bubble is that the technology is legit and already creating value (allegedly). This argument is always used in relative comparison to the financial crisis from 2008, one that was primarily driven by housing market speculation, obscure secondary markets like synthetic CDOs, and outright fraud.

Instead, here we are looking at, simplistically speaking, a bunch of investors excited about a technology that will “change the world.”

The counterargument here is not that this isn’t true; everyone agrees AI is here to stay and will change the world, but instead that we are being premature about its impact; in a way, we are correct to be excited, but we are way ahead of ourselves, and that real change will take time.

Doomers often use this link to connect the dots with the dot-com bubble, where the technology driving the craze, the open Internet, was indeed transformative.

However, the market at the time went way ahead of itself and paid the price by investing in companies that had no real business and were simply riding the craze.

But is this a fair comparison to what is happening today? No, but the narrative serves really well for those who want to keep the party going. Fueled by recency bias, the discussion always shifts to comparing today with the dot-com era.

Let’s understand why this is so convenient to discredit those concerned about the current market, and also why it’s a grave mistake not to be.

Valuations aren’t remotely comparable

As I was saying, PE is the metric that people use to convince themselves of… what they want to convince themselves. However, if you truly want to make an honest comparison, well, there’s really no comparison at all.

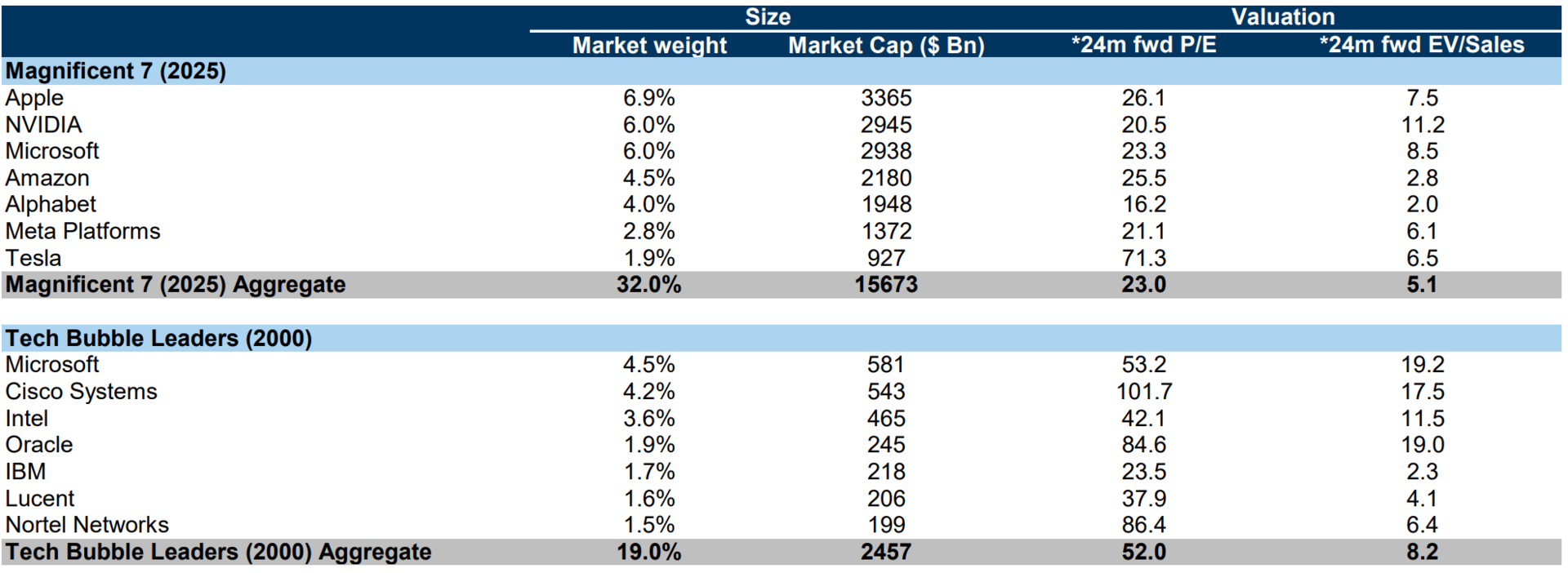

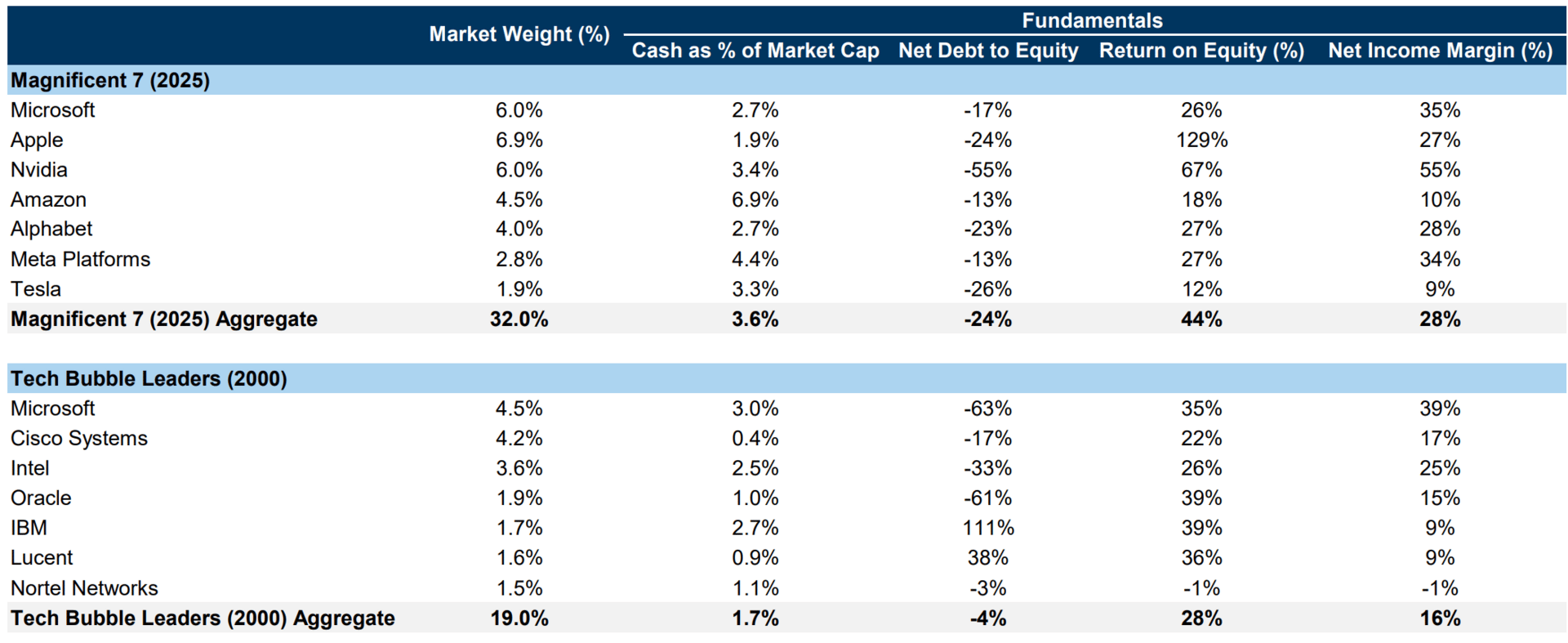

Looking below, we see that the top stocks in each era had some similarities, but the dot-com leaders were considerably more expensive compared to both earnings and future projected earnings, with all of them commanding not only very high PEs (not shown, but the Nasdaq reached a peak of 120x for the entire index) but also having insanely high forward PEs (shown below), meaning that, even after accounting for future revenue growth, the top dot-com stocks still had an average 24-months forward PE of 52, which is higher than NVIDIA’s current PE and almost two times higher its current 12-month forward PE of 29.

Source: Goldman Sachs

In plain English, current market darlings are much, much cheaper in comparison if we look at projected growth.

It’s worth pointing out that the numbers above for the Mag 7 are outdated (data from March), and current market weights and caps have changed (Mag 7 are more expensive today), but the points still stands as they aren’t remotely close to dot-com levels.

Importantly, modern darlings are vastly more profitable than their dot-com counterparts and far less in debt (except for modern-day Oracle, not shown below):

But what if we look beyond the Mag 7 and at technology companies as a whole?

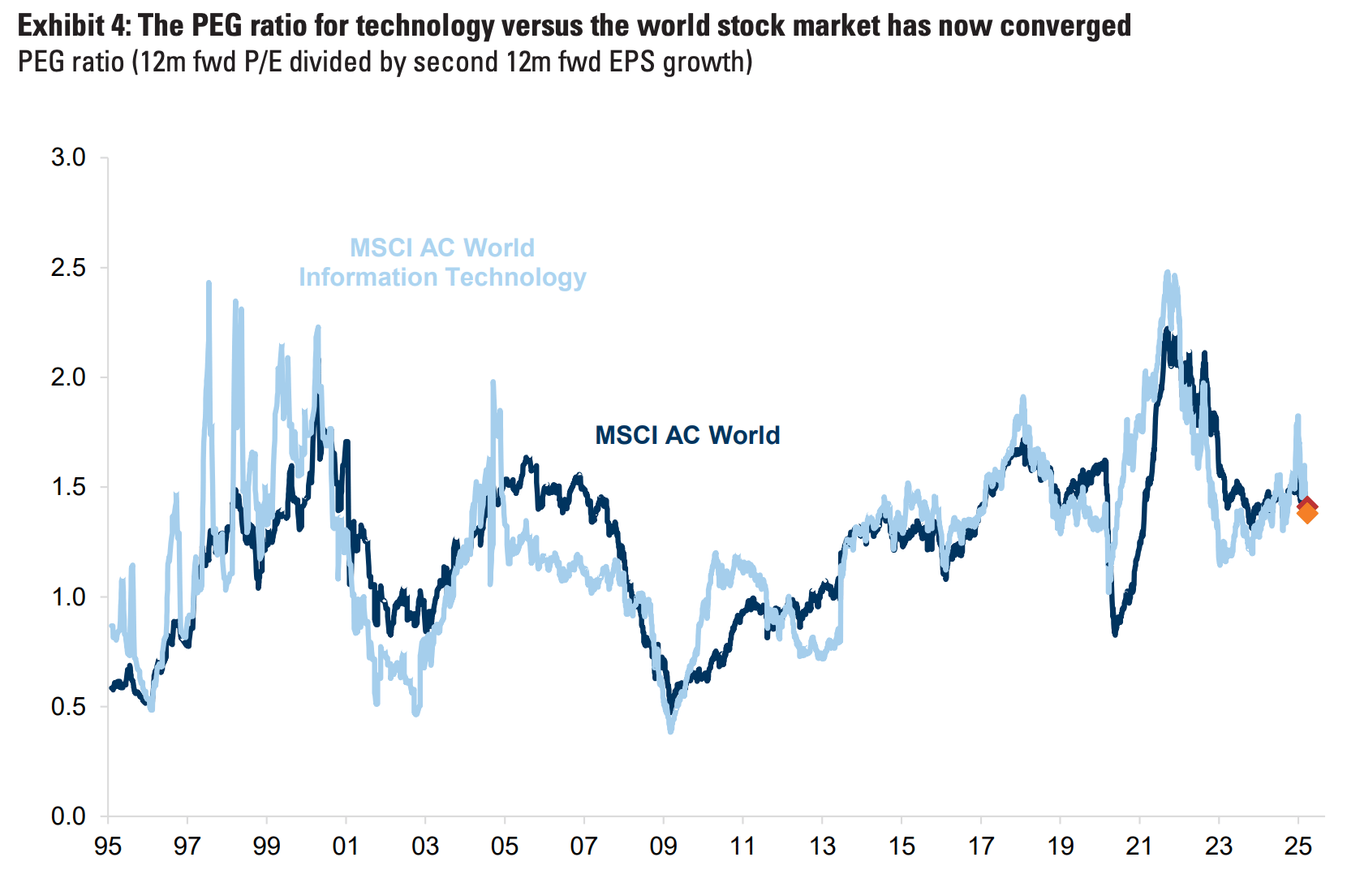

We also have European or Chinese AI stocks to account for. Surprisingly, as recent as March 2025, if we compare global tech stocks to the rest in terms of PEG (PE ratio scaled by future growth), valuations had actually converged.

Source: Goldman

In other words, if we account for future earnings growth, tech stocks are valued at the same prices as non-tech stocks because their much more explosive projected earnings growth justifies their higher prices today.

So, not only are AI stocks way cheaper than the dot-com darlings, they aren’t even expensive at all if we adjust for earnings growth compared to non-AI stocks.

Thank god, no bubble! Wrong. Or, at the very least, this particular framing is shortsighted. There’s much more to it, starting with market concentration.

The “One-Decision” Companies

One thing people often neglect is that, in the dot-com bubble, stocks were much less concentrated, with the top seven stocks representing “just” 19% of the total market.

Today, the Mag 7 accounts for 34% of the S&P500, meaning seven stocks represent a third of the total value in an index of the top 500 companies in the US.

And why is this relevant? Well, because it puts us on a path toward another concerning period: the 1970s.

At the height of the stock market in 1973, a group of top companies known as the ‘Nifty Fifty’ (the long tail of members varies depending on the source) commanded up to 45% of the total market value.

This select group included Coca-Cola, IBM, McDonald’s, Disney, Polaroid, Xerox, and Avon Products, among others.

We’ll talk later about them in more detail, but these weren’t pets.com-type useless companies from the dot-com era; these were companies that were leaders in their industries, with strong earnings and earnings growth, to the point that many of them are alive and well today.

Instead, what makes them relevant to today’s discussion is the aura they had in the eyes of investors.

These were considered “one-decision” stocks, companies where the only option was to buy. Selling was never an option. The sentiment was that these would never stop growing; the only decision was to buy, no matter the price.

They were all great companies, but that really didn’t matter that much anymore. Investing in them was driven not by price discipline (e.g., discounted cash flows analysis), but by the unwavering belief that future growth would allow them to grow into their valuation, no matter how high it went.

Sounds familiar?

Despite the similarities, at the height of the market in 1973, the median PE of the Nifty Fifty stocks was an impressive 46, very close to NVIDIA and higher than all other Mag 7 except for Tesla, and with companies like McDonald’s or Polaroid way over 80 and 90, respectively.

Sounds like the Nifty Fifty were also much more expensive than current tech stocks, but just like people like to cherry-pick Polaroid’s case, we can also highlight Tesla or Palantir showing equally irrational (or much worse) investor behavior.

So, what is the right way to compare our current state with the past? And the answer lies in going beyond valuations, uncovering hidden signals that may help us predict what will happen this time, because, as Mark Twain reminded us, history may not repeat itself, but it rhymes.

The Events that Led to the Disaster

After the US won the Second World War, it entered a decades-long period of incredible growth, optimism, and an unfaltering belief that everything was great, a time reminiscent of the roaring twenties after the First World War. However, this period of overoptimism ended with the massive Nifty Fifty crash that cut markets in half.

But why? What went wrong? Well, a lot.

Shock after shock

In the late 1960s, the US arrived at the end of a long, confidence-soaked expansion. While Vietnam War spending surged, monetary policy leaned easy (low interest rates, aka cheap money, to incentivize consumption).

But soon enough, inflation pressures that had been contained for years began to leak into wages and prices. After a brutal 1968–70 bear market burned the small-cap craze, investors massively rotated to the large stocks as a safe haven. As money concentrated, a “two-tier market” emerged.

On one tier sat the glamour growth companies, which came to be known as the Nifty Fifty, delivering visible revenue expansion, fat margins, and brand dominance, leading to “one decision” stocks we mentioned earlier.

On the other tier sat everyone else: cyclicals, smaller industrials, and “ordinary” businesses that still retained the scars of the 1969–70 downturn.

And to top it all, the massive policy changes at the beginning of the decade amplified the detachment.

In August 1971, the Nixon administration suspended dollar convertibility into gold (Nixon shock), effectively ending the Bretton Woods system and initiating the era of floating exchange rates (now, the value of the dollar would be defined by its demand relative to other fiduciary currencies, not based on its Bretton Woods-era fixed exchange rates and direct value in gold at $35 per ounce), which led to speculation and overall inflation.

The White House then layered on wage-price controls to suppress symptoms without curing causes, while pushing for pre-government election stimulus in 1972. In plain English, it was an election year, so monetary tightening was not on the menu (something we also experienced recently, as we’ll see later).

With the government and the Fed ignoring the inflation risks and not hiking interest rates, the discount rate (opportunity cost) investors apply to long-duration assets decreased (i.e, stocks became even more attractive as safer investments like bonds saw returns eaten up by inflation), which made investors even more tempted to move toward the Nifty Fifties.

And as their earnings lines were smooth, their stories strong, and the flows relentless, their valuations continued to increase, unwarranted by actual earnings, but simply because they were going higher.

In other words, “I’m investing not because of the intrinsic value of companies going up, but because they are going up.”

At this point, investing became trading. By late 1972, valuations in the darlings had sprinted far ahead of both their own cash-flow trajectories and the multiples investors were willing to pay for the rest of the market. Howe er, the index appeared mainly healthy because its most expensive components did most of the lifting (sounds familiar?).

Then the macro tide turned.

In early 1973, inflation accelerated, the dollar wobbled, and the Federal Reserve under Arthur Burns shifted from accommodation toward tightening… a tad bit too late.

Crucially, in October 1973, the Yom Kippur War triggered the Arab oil embargo, sending oil prices sharply higher and pushing the economy toward recession. Stagflation, a mix of slowing growth and rising prices, soon arrived. The Fed had reacted too late, and now inflation was still out of control while the macro environment worsened due to the very-late monetary tightening.

Now, with interest rates rising, expected return rates (discount rates) have increased, compressing the lofty multiples. In other words, the opportunity cost of investing at those valuations became so high that nobody was willing to do it anymore.

For example, if I’m valuing a company based on the cash it’s expected to generate over the next five years, and interest rates suddenly spike, the return I would demand from a risky stock (say, one of the Nifty Fifty) rises as well. That’s because the alternative, investing in bonds, has become more attractive since bond yields increase alongside interest rates. In other words, when “risk-free” returns like US treasury bonds go up, the required return on equities must also rise to justify taking on additional risk.

And, suddenly, the “one-decision” aura evaporated almost overnight. Just like buying had begotten more buying, selling begat more selling.

By the end of 1974, the S&P 500 had lost nearly 48% of its value, the Dow Jones Industrial Average had fallen from about 1,050 to 577, and trading volumes on the NYSE dropped sharply as panic and exhaustion set in. It was one of the steepest declines since the Great Depression.

What the multiple giveth, the multiple taketh.

At this point, I’m sure you’ve noticed several things: the events that led to this horrific crash are incredibly similar to… the present.

But how specifically? And what is the single AI metric that will define if the bubble pops? How will that potential pop carry itself out? Let’s answer all these questions while revealing fascinating lessons we can instantly apply today.

Subscribe to Full Premium package to read the rest.

Become a paying subscriber of Full Premium package to get access to this post and other subscriber-only content.

UpgradeA subscription gets you:

- NO ADS

- An additional insights email on Tuesdays

- Gain access to TheWhiteBox's knowledge base to access four times more content than the free version on markets, cutting-edge research, company deep dives, AI engineering tips, & more