THEWHITEBOX

TLDR;

Welcome back! This week, we have lots to talk about. From learning how an AI that gets a gold medal in maths is built, to what are possibly two of the most important trades in 2026, memory and debt (currency debasement is most likely a better description), this post will put you up to date of what’s going on in technology, markets, and product, the latter with a new product that might send UI designers to a better life.

Enjoy!

THEWHITEBOX

Things You’ve Missed for not being Premium

On Tuesday, we took a look at the US’s state-backed AI acceleration push, Google’s escalating TPU challenge, legendary researcher Ilya Sutskever’s argument that AI is hitting its limits, and the rapid shift from chat-based models to interactive AI products, including Google’s amazing Dynamic View feature, and more.

FOUNDRY BUSINESS

Intel to become Apple’s low-end M chip manufacturer

Unbeknownst to many, NVIDIA, AMD, Apple, or Qualcomm don’t manufacture the chips they design.

Instead, they send the ‘tape out’ to TSMC, a Taiwanese mega corp in charge of manufacturing more than 90% of the entire world’s advanced chips (7 nanometers and below)… precisely the types of chips that NVIDIA’s GPUs, AMD’s CPUs/GPUs, Apple’s iPhone, or Qualcomm’s chips need to work.

As you may realize, given that a company has most of its factories on the west coast of an island 160 km (~100 miles) from Mainland China, while the People’s Republic of China argues that the island is theirs, this is probably not the best national security situation.

Nevertheless, in the event of a non-peaceful invasion, this would cause massive destruction of US equity markets, as most of its largest companies would lose the capacity to deliver products. Thus, for the longest time, the US Government has sought the emergence of a US national champion capable of manufacturing these chips domestically.

However, this has been mostly a failure, considering we are talking about what’s possibly the most complex and advanced manufacturing process in the world, executed in factories (known as ‘fabs’) which each cost $20 billion on average to build.

To put it into perspective, the EUV machine that prints circuits onto silicon wafers, built by Dutch company ASML, costs around $400 million… a piece. And that’s just one part of the entire fab!

Seeing its chip design business destroyed by its rivals, Intel has decided to position itself as a foundry national champion, betting strongly on the fab business (the business of manufacturing chips for others).

And now, it seems it’s well-positioned to win the contract to manufacture Apple’s low-end M chips (used in MacBook Airs and iPads) as soon as 2027, making it the first big company that could see its full-blown dependency on TSMC being alleviated by having a decent portion of its chips built at home.

NVIDIA’s Blackwell chips can be produced at TSMC’s Arizona Fab, as they use a 4nm process node. Not sure about lower process nodes, though.

This is, of course, a massive—yet speculative—victory for Intel, which rose 10% on the news.

TheWhiteBox’s takeaway:

In this newsletter, we have been discussing the great stock opportunity Intel could be, even before both the US Government and NVIDIA invested heavily in the company. The reason was simple: the US desperately needs a foundry national champion.

If Intel delivers on its foundry roadmap (and this is all but guaranteed), we’re talking about the US’ national champion in one of the most critical chokepoints in the entire semiconductor supply chain.

For the US, having its biggest corporations not depend on TSMC is nothing short of fundamental to its national security interests, and Intel is the only company (to date) in a position to solve that problem.

Thus, it’s hard to be pessimistic on a company that, despite doing everything wrong over the last two decades (basically surviving thanks to the CHIPs act subsidies, which Trump overturned and instead took a more aggressive approach of directly investing in them), feels too important to fail.

Now, does this solve Apple’s dependency on TSMC?

Hard no; the most advanced chips are TSMC territory and will remain that way—to mitigate the obvious risks here, the US Government (bipartisan position) has been pressuring TSMC to open fabs in the US, with the Arizona one already in production, we mentioned above.

And importantly, it’s not in TSMC’s interest at all. TSMC was basically “forced” to open this fab and is not particularly happy about this, considering they serve as these assets serve Taiwan as what’s known as the “Silicon Shield”; the strategic importance of Taiwan’s foundry business deters China from making strong moves because it would not only cause a massive reaction from the US, it’s also “killing” several global supply chains.

This would basically send the world into chaos and put everyone against them. Put another way, just like having its entire foundry dependence on Taiwan is a problem for the US, it’s a national security asset for Taiwan.

Therefore, don’t expect TSMC to relocate everything to the US. Instead, let me be very clear that, no matter the mitigation actions, if China invades Taiwan or blocks the Taiwan Strait, the entire world is going into a deep recession, no questions asked.

On a final note, the US has other foundries like Global Foundries, but these build chips with much older nodes, in the 12-nanometer range and above, which are still very important for several things, but are very far from more advanced use cases like smartphones or AI hardware.

RAM CRUNCH

The RAM Issue Worsens

Something my paid subscribers have already known for quite some time is that RAM, the type of memory used for both gaming and for AI servers, is suffering a steep supply crunch, especially on the gaming/consumer hardware side, as the only three providers, Sk Hynix, Samsung, and Micron, are prioritizing giving capacity to the much more lucrative AI business.

Here’s why I recommended one of these three stocks to my Full Premium Subscribers as my big AI bet for 2026, based not only on the supply conditions, but also a more detailed analysis that puts one of them above the rest.

These companies have limited capacity to build, and they are prioritizing HBM (High Bandwidth Memory) chips used by NVIDIA, AMD, and Google for their AI servers, rather than GDDR and LPDDR RAM chips you see in gaming GPUs and consumer hardware like laptops, respectively.

From what I understand, Apple secured LPDDR capacity well in advance for its Macbooks, so they should be good.

This has resulted in RAM prices skyrocketing at insane speeds (quintupled in two months), setting new records every day. For instance, 96GB of DDR5, not even the most advanced memory type, is retailing at $1,500, complete madness.

But then why do these three companies have quite low forward PEs? There’s a reason that I cover the answer to that in my analysis of the one I invested in.

And now, according to recent rumors first shared by a Weibo source, the situation is so grave that NVIDIA may have stopped supplying video memory (VRAM) chips alongside its gaming GPU dies to its board partners (AIBs).

For those unaware, the actual packaging for an NVIDIA gaming GPU is not provided by NVIDIA. NVIDIA usually provides the chip and the VRAM dies (chips), and AIB (Add-In Board) partners, like ASUS, give the rest of the product, handling PCB design, cooling, and assembly.

However, that may be changing due to a global memory shortage. Thus, if the rumor is true, partners will have to procure VRAM themselves from the usual memory-chip vendors (i.e., the big three mentioned above).

For big firms with established relationships and procurement capacity, this won’t be a significant disruption. For smaller or mid-sized vendors, those without deep ties to memory suppliers, this could lead to serious margin pressure, delays, or even push some out of the market.

This is terrible news for NVIDIA, which will always prefer having a diversified pool of AIBs so that negotiations with them give it more power. If AIBs concentrate, that could put pressure on NVIDIA to cut costs in its GPU dies (a similar effect to NVIDIA having to compete with Google at the AI business level).

But NVIDIA issues aside, the takeaway is that the memory crunch we’ve been talking about for weeks is very real and only getting worse, and many experts believe it will move well into 2026 (Epic Games’ CEO argues this will last for years in the gaming sector).

On NVIDIA’s side, the move signals how severe the current memory crunch has become, to the point that NVIDIA itself, probably the memory chip companies’ most important partner, finds it unsustainable to continue bundling VRAM under present market conditions.

Beware, though, this remains a rumor; nothing is confirmed yet. If verified, supply chains, card pricing, and availability (especially from smaller manufacturers) could all be disrupted. My prediction that memory will be one of the big trades in 2026 looks better by the day.

VIDEO GENERATION STARTUPS

Luma AI Secures $900 Million

In what is clearly another step in the already very strong relationship between the US and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Luma AI, the U.S.-based generative AI firm known for its multimodal models, has successfully raised $900 million in a Series C funding round. The funding was led by HUMAIN, a full-stack AI company backed by Saudi Arabia's Public Investment Fund (PIF).

This massive capital injection is directly tied to a strategic partnership that positions Luma AI as a key customer and partner in the development of "Project Halo," a monumental 2-gigawatt (2GW) AI supercluster being built by HUMAIN in Saudi Arabia. This supercluster is set to be one of the world's largest computing infrastructures, with construction slated to begin in 2026.

The purpose of Project Halo is to provide the extreme compute capacity needed to train the next generation of AI systems—specifically, Luma's "World Models."

These models go beyond traditional large language models (LLMs) by learning from multimodal data (video, audio, images, and language) to simulate and understand the physical world. In other words, world models are a specific type of AI model that “understands the world around it” and can therefore adapt and survive in an ever-changing environment.

As you may have guessed, this capability is aimed at applications across robotics (as the brain of the robots), entertainment, design, and personalized education.

TheWhiteBox’s takeaway:

I’m speculating, but it appears that US startups are seeing funding dry up and are thus looking to the Middle East, especially now that the US Government is more open to exporting NVIDIA GPUs there.

The other point I wanted to make is not related to the funding at all, but my technological skepticism about how they are building world models. The reason is that Luma approaches world models the same—mistaken, I believe—way Google does: by generating the world.

In other words, the model learns what will happen in the world by generating it (e.g., imagine your brain generated every new moment in your life with striking detail).

The reasoning is that if a model can simulate new frames that depict what happens next, it’s indirectly encoding the cause-and-effect relationships in the world (e.g., if I can predict how waves will form as soon as my boat turns left, I can assume I understand water physics).

The problem with this approach, famously criticised by one man in particular, Yann LeCun, Meta’s ex-Chief AI Scientist, is that by being “forced” to generate every single detail in the frame, the model struggles to “understand what really matters”.

The human brain isn’t like a model that generates the whole next sequence. It predicts only what matters for action. For example, when you’re driving, and a hare crosses the road, your attention and prediction shift to the right side because that’s where quick movement matters. The rock on the left is still there, but only as a faint, low-priority detail your brain will most likely ignore. Which is to say, the brain updates a minimal sketch of the world, not a full continuation.

Therefore, the main point of criticism here is that by training world models on pixel-generators such as Google’s Veo or Luma’s models, the model will never learn to pay attention to what matters. But anyways, congrats on the huge funding round.

CYBERSECURITY

OpenAI API Cyber Leak

OpenAI has cut ties with analytics provider Mixpanel after a security breach at Mixpanel exposed limited (allegedly) information associated with some users of OpenAI’s developer API platform.

The incident occurred when Mixpanel (which OpenAI used for web analytics on its API interface) suffered unauthorized access on November 9. On November 25, Mixpanel notified OpenAI that an attacker had exported a dataset containing metadata from some API accounts.

According to OpenAI’s disclosure, the compromised data was limited to account profile and analytics metadata: names, email addresses, approximate location (city/state/country derived from the browser), browser and OS used, referring websites, and organization or user IDs. No sensitive information, such as chat content, API requests/responses, API keys, passwords, payment details, or government IDs, was exposed (again, allegedly).

In response, the company removed Mixpanel from production, began notifying affected users (yours truly), and initiated a broader review of vendor security practices. OpenAI has warned that the exposed metadata could be used in phishing or social-engineering attacks, advising vigilance. However, it stated there is no need for users to reset passwords or secure credentials.

TheWhiteBox’s takeaway:

I received notice from OpenAI that this had happened, so I was already aware of it before it became public, as someone affected as an API user.

Overall, this perfectly illustrates the delicate reality when using any Internet service; you are always at risk of being compromised. And as I’ve stated multiple times, I intend to eventually migrate most of my AI workloads to local models, especially the more “delicate” ones.

Thus, I also predict that the market for AI consumer hardware, led by companies like Apple, will eventually see explosive growth as AI becomes increasingly mainstream (and easier to run locally), unless RAM prices price everyone out, of course.

UI/UX DESIGN AND FRONTEND

From Image to Design In Seconds

Look, I’m not a fan of “killing jobs”, but boy are frontend and UI designers going to struggle because of AI’s capabilities.

With this AI tool called Blackbox, a simple image gets immediately transformed into an interactive Figma design, which means your customers can now generate the Figma designs themselves without needing you at all; just finding the image they want to replicate.

Then, as Figma has its own MCP server, give access to an AI model with MCP support and ask it to code the design, and there you have it, the frontend you wanted without any expertise in design or frontend coding (by the way, Blackbox is an MCP too).

TheWhiteBox’s takeaway:

But does this mean these jobs will disappear? No, it’s just that the bar for monetizable work is now higher. In other words, you have to be better than the AI for people wanting to pay you (because you’re definitely going to be more expensive).

Luckily for you, you can be better than AIs. The reason is that these models are trained to match a certain distribution of ‘what good design looks like’ assembled by their trainers. Surely they can generate new stuff, but this stuff will always be “similar” to what they have seen.

Therefore, you’re essentially competing against the ‘taste’ of the designers who assembled the dataset used to train these models. In other words, this ain’t no superhuman output, it’s just “human output” that happens to be provided by AIs.

Therefore, as I always say when referring to creative jobs, originality, uniqueness, and superior taste will always be handsomely rewarded. In other words, I can’t fathom a future where AI generations are better than our top designers; the imagination of their creators will always limit them.

In a nutshell, human jobs will still exist in 20 years, even web design, because the desire for human creations will endure, just like interest in human chess matches is at historical levels despite humans being neatly inferior to AIs at the game.

But I won’t sugarcoat this: to rise above AI, you’ll have to be good… or at least different.

SLIDES

From Data to Slides in Seconds

Moonshot AI, the Chinese AI Lab behind Kimi, which is possibly the most advanced open-source model, has released a new feature in its app called ‘Agentic slides’, which promises the first-ever actually good experience of an AI creating slides. And I must say, the demos are very promising.

TheWhiteBox’s takeaway:

This feels like the first actually good agentic slide scaffold for AI models. However, a word of caution.

This is a Chinese web service, so there’s a non-zero chance they’ll steal your data, even if the models they are using under the hood are things like Nano Banana Pro; there’s really nothing stopping them from stealing the data anyway. Heck, they might even leak your data without even intending it.

Not saying it will happen, but proceed at your own risk. That said, don’t confuse this with fear of Chinese open-source models, either. Once these are uploaded to HuggingFace, they are secure to download and use in your own systems.

In other words, the cybersecurity risk here isn't that they are running the Kimi AI model; it’s that you’re sending data to a Chinese web service, which is two totally different things.

But beyond that, man, wouldn’t the world be a much better place if the West and China trusted each other? The product looks pretty legit (I haven’t tried it; the web was congested when I tried), and their models are extremely good (as we’ll see below).

PROMPTING

How to Prompt Nano Banana Pro (Like a Pro)

Google’s Nano Banana Pro has taken the world by storm. While most of my friends remain oblivious to AI progress and resort to the basics, I was surprised by how many people reached out to me in awe of this model.

When that happens, you know it’s good.

This interesting Substack article covers the nitty-gritty of good prompting of image generation models. The reason I give you this instead of giving you my suggestions is that, well, I would not consider myself an expert on image generation; my prompts aren’t nearly as detailed as this guy’s, so it’s only fair I give you the opinions of experts instead of mine.

Here’s the gist:

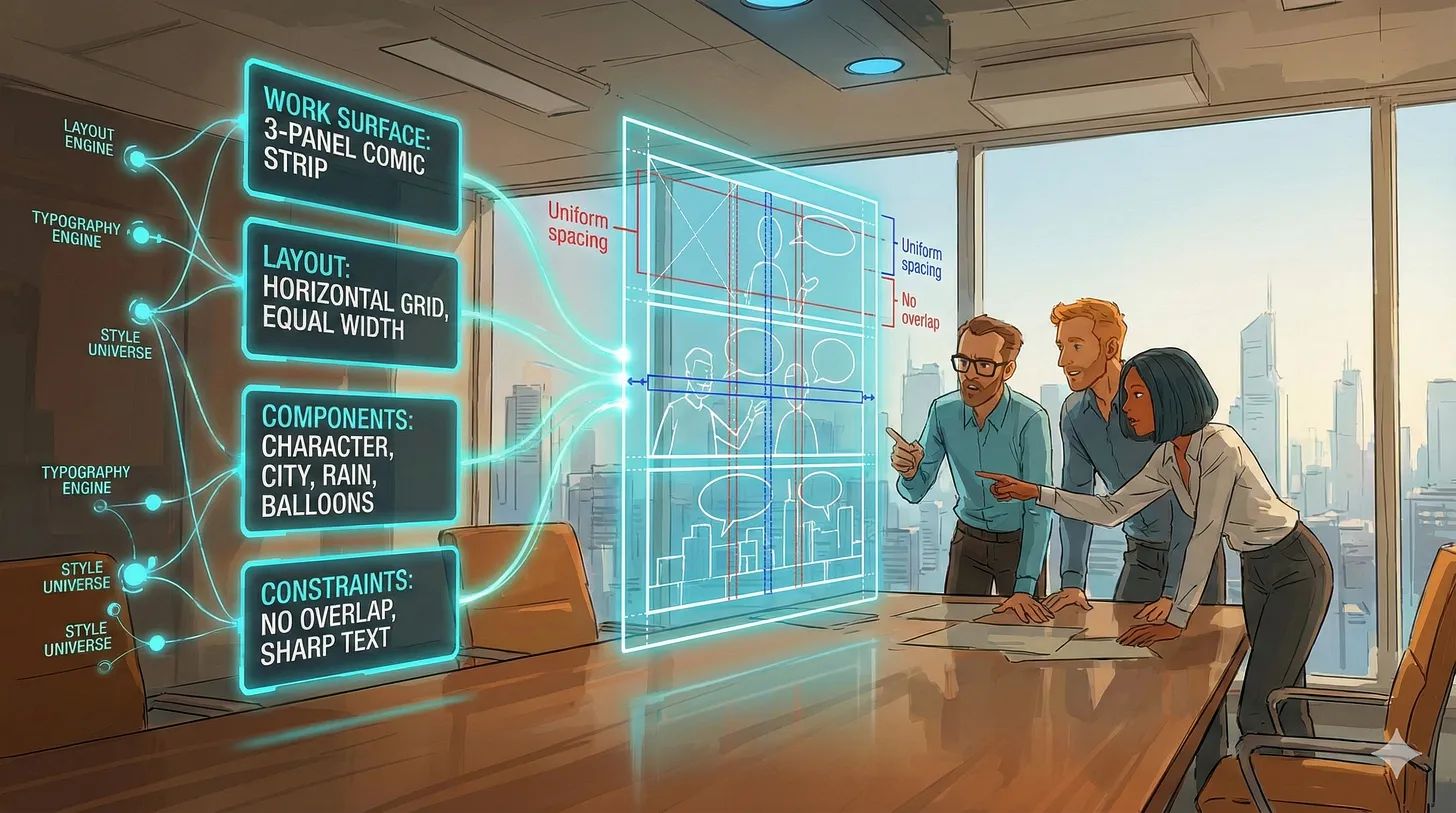

The model (Nano Banana Pro) works best when prompts act like design briefs, not casual requests.

Start by defining the work surface: the visual you want (infographic, comic page, dashboard, diagram).

Specify the layout before anything else: number of panels or sections, their arrangement, spacing, and proportions.

List every component the image must contain so the model knows exactly what to include (charts, labels, icons, characters, backgrounds)—note, this is probably the most important detail. Let’s not forget the model conditions on your prompt to try and semantically match it, so the more you specify, the more information the model has to “play with”.

Add constraints and rules to prevent errors: consistent style, fixed color palette, no overlapping elements, uniform spacing, stable character appearance.

A worked example shows a noir comic page where layout, components, style, and constraints are all explicitly defined. Then, the author built a prompt generator following this structure and used it to turn a story into coherent visual pages.

In a nutshell, the core idea is to treat prompts as detailed specifications.

In a nutshell, be structured, use components, and set constraints to achieve the most reliable results.

MATHS

DeepSeek’s Gold Model. A first in Open-source

DeepSeek doesn’t publish that much research or models these days. But when they do, it’s almost always (or always) worth analyzing in detail.

And this time was no exception, as they’ve presented the first open-source implementation of a model that earns the gold medal in mathematical proofs, matching the much-publicized results obtained by Google and OpenAI.

Luckily, unlike Google and OpenAI’s implementations, we know how to build such a model this time, and it just confirms what we already suspected: there’s no frontier moat, just a few weeks’ lag between closed and open models.

Hence, compute and data remain the only meaningful frontier in performance (recall that the more compute is thrown into the task, the better the model performs, and closed Labs have access to much more compute).

But is the model any good?

On IMO 2025, the model solves 5 out of 6 problems and reaches about 83% of the total points, which is right in the range of top human gold medalists.

On China’s CMO 2024, it does similarly well, fully solving four problems and earning partial credit on another for around 74% of the total score.

These are not cherry-picked toy benchmarks; they are the hardest high-school competitions in the world, graded the same way human contestants are.

On the undergraduate side, things get more interesting. On Putnam 2024, which is notoriously brutal even for math olympiad veterans, DeepSeekMath-V2 scores 118 out of 120 points, with the highest human score that year being 90.

So, how did they pull it off?

To understand this, we first need to remind ourselves how frontier models are built these days.

You get what you optimize for

Frontier AIs train Large Language Models (LLMs) first using imitation learning on Internet-scale data. That is, they are shown “the entire Internet” and forced to imitate it word-for-word.

But this limits how much models can really learn, as they aren’t allowed to explore alternative solutions. This might not be necessary to learn the world’s capital cities, but on things like math, if you always expose the model to the golden solution, they are heavily incentivized to memorize it instead of actually understanding it, just like a kid that studies by copying solutions to past exams will struggle with new problems.

To solve this, we train them using RL (Reinforcement Learning), where we don’t show the model the solution (only the answer), and it has to “find its way” to it.

This incentivizes it to explore different ways to solve problems. Through this exploration, the model eventually finds the way, and the solution is then reinforced so that future model iterations are more likely to generate that solution, reasoning for similar problems.

The issue is that if we run this naively, giving zero guidance to the model, it might never find the answer. Here, we have two angles to work with:

Prior strength. Not only do we need a model with a good enough prior (e.g., you can’t teach a dog to speak),

Rewards. We also need to give it some guidance during the exploration (you can’t expect your friend to find the object in the ‘hot or cold’ game if you never tell them if they are hot or cold).

The latter introduces the idea of ‘reward mechanisms’, which provide ‘action feedback’ to the model, guiding it during exploration (e.g., saying “hot” or “cold” to help your friend find the object). This sounds great, but it has a big issue: unlike in the game, hot or cold, this is notoriously hard (the most challenging part in all RL training, actually).

Say you’re teaching an AI to solve maths proofs. The idea of reward is to provide intermediate guidance, aka “tell the model if it’s heading in the right direction.” Some cases are easy (e.g., the model adds 2+2 and gets 5), but others are notoriously tricky to assess in terms of quality. This is formally known as the credit assignment problem.

In fact, in our case study today, mathematical proofs, humans can identify if a proof is heading in the right direction without seeing the answer, in the same way we can also see that putting the king in direct path of the opponent's queen is probably not going to end well, without even having the opponent checkmate you.

In some cases, such as maths or coding, we can provide meaningful intermediate feedback (e.g., running a compiler to check whether the code is syntactically correct). However, the problem is hard enough that, most of the time, we actually rely a lot on the end feedback (correct or incorrect) and hope the prior (the LLM) is strong enough to find its way with little guidance.

In fact, one of the greatest criticisms in RL, as Andrej Karpathy pointed out and Ilya Sutskever did so too recently, is that we don’t verify whether the reasoning process that got to the right answer is correct; the model might have added 2+2=5 during the process and still stumbling into the correct answer, and we still reinforce that action too as it’s in the reasoning chain of the right answer.

Instead, what we ideally want is not only to ensure all the steps are correct, but we also want the model to be able to identify its own mistakes. But how do we do that?

The shortest answer is verifiers, which provide that intermediate feedback we covet. Some can be automatic, like compilers or maths engines, but, in practice, top AI Labs resort to using LLM verifiers; literally using LLMs to serve as intermediate smart verifiers that read the generator’s reasoning (the model we are training) and assess the quality.

This works well, but introduces another issue: the upper bound of the generator’s “intelligence” is the verifier’s “intelligence,” so you have to update both continually. And this is precisely what DeepSeek has done to build the first open-source gold medalist model.

Before we proceed to explaining what DeepSeek did, the main thing I want you to take away is that, in AI, there’s no magic, and the model you get is exactly what you’re optimizing for. In other words, what the model learns or doesn’t learn is totally dependent on what you incentivize it to learn.

This is a particularly intuitive way to look at AIs, because it lets us reason in first principles about what researchers are doing. This may sound weird, but it’ll make sense in a minute.

DeepSeek’s Gold Medal Recipe

DeepSeek’s recipe is, at its core, a carefully engineered feedback loop between three roles:

a proof generator,

a proof verifier,

and a “verifier of the verifier” (a meta-verifier).

In short, DeepSeek’s entire recipe is basically a story of repeatedly tightening the definition of “good” and forcing the model to live up to it.

They start from a standard SFT-trained LLM (an LLM trained to imitate good solution traces to maths problems). However, as we mentioned earlier, there’s a limit to what a model can learn when it’s only imitating. We need RL.

Therefore, the first shift in optimization is to train a dedicated verifier: a model that reads a problem and a proof and is rewarded for assigning the same 0/0.5/1 score as a human grader would, and for explaining its judgment in a clean, structured way. In first principles, the model is learning to score proofs by finding the patterns that “make a good proof”.

However, this verifier is not enough, as the patterns it might find are too superficial. As it’s not scrutinizing each step, the model might arrive to conclusions such as “long proof → proof” and vice versa, or “good proof structure → correct proof“. As you know, correlation does not imply causation, so these could very well be spurious correlations.

To solve this, they add a ‘meta-verifier’ whose only job is to judge whether those explanations are themselves accurate and justified, and they feed that judgment back as an extra reward, so the verifier is now optimizing for “truthful, well-founded critique,” not just “right numeric score.” Here, we are now incentivizing the model to verify the proof's actual quality.

And once the verifier has embodied the grading rubric, they flip focus to the generator (the model that generates the proofs). By training the generator against the verifier, we now have a way to optimize it to write proofs that the verifier scores highly and to self-evaluate those proofs in the same language the meta-verifier uses.

During RL, the generator is explicitly rewarded both for the quality of the proof and for how honestly and accurately it scores itself, as judged by the verifier in meta-verification mode.

In other words, the generator is no longer learning “say whatever leads to the right answer,” it is learning “produce a proof that would genuinely convince this critic, and don’t lie about its flaws.”

All this makes AI sound easy, right? Just train it to be good!

The issue is that AI theory is actually easy, but the engineering side… oh boy. Beyond training stability issues (making the model actually learn, which is much more nuanced than it sounds), building the correct training data to create a gold-medal AI model requires prominent maths experts (it’s not uncommon to see Fields medal winners participating in AI maths training).

The final question here is: how do we make this system learn autonomously and improve over harder problems over time, and without the need for human support?

To be superhuman, it can’t be ‘human.’

Once the generator is reasonably strong, they let it tackle new, harder problems and generate many proofs.

For each proof, they sample the verifier many times to surface potential issues, then sample it again in meta-verification mode to check which alleged problems are real. If multiple meta-verifications agree that “this proof is fundamentally broken” or “this proof is essentially correct,” that becomes an automatic label.

Those auto-labeled proofs are then used to further train the verifier, which in turn becomes a sharper critic for the next round of generator RL.

At every stage, they are not doing magic; they are just redefining and sharpening the reward so the system is always optimizing for precisely what they care about: faithful detection of errors on the verifier side, and genuinely correct, self-aware proofs on the generator side.

Put another way, there’s really no problem AIs can’t solve if we can define a good reward mechanism and train a good prior.

But without humans, we don’t have a way to push it further, or to verify correctness using ground truth data, correct? And here is where a point I mentioned earlier comes into play: verification is easier than discovery.

Once an AI is strong enough, verifying whether the output is correct or not is much easier than finding the result. In other words, we can get self-improving verifiers that don’t require human oversight because the verifier can identify, even for new proofs, if they look right. And with the power of exploration (the generation just trying out new stuff), it’s not totally unfathomable that, by running this at scale, the system may find new proofs to maths problems thanks to this self-improving mechanism that reads like this:

Generator: “I’ve tried this very weird approach.”

Verifier: “Mmm, weird, but feels right.”

“Blindly” train both on this new proof.

It must be said that, to reduce the chance of error, they run every promising proof across several proof generations, verifications, and meta-verifications, squeezing out noise (i.e., if a pattern repeats a lot across several tries, it becomes more likely to be correct).

In other words, it’s the fact that verification can be non-supervised (because it’s much easier to know something is wrong than to discover that something is) that allows this system to self-improve.

And, case in point, the last two stages of self-improvement that took the model to the gold medal were totally unsupervised by humans.

Pretty brilliant, isn’t it? And pretty scary.

Closing Thoughts

Another week, another long TheWhiteBox newsletter. Not only have we seen the emergence of the first open-source system to score a gold medal in a mathematics Olympiad, but we now know how to build such a system without requiring closed state-of-the-art models.

But we have also noticed less encouraging trends in markets, such as RAM supply so tight that even NVIDIA struggles to get it for gaming GPUs, or the appetite for big AI investments in equity markets may be drying up.

The first one doesn’t officially affect AI servers yet, but it takes no genius to know RAM suppliers are going to raise prices and eat into the margins of NVIDIA et al. How will the market take that? Probably not great.

As for the latter, it might be the precursor to what could soon become a guaranteed reality: a very significant portion of 2026 AI spending will be debt-financed. But more on that and the problems it raises for another day.

And the last takeaway is job displacements, which will only get worse in 2026 as AI capabilities progress. And with the US job market (and soon-to-be European markets) already in a precarious position, 2026 might be the year of the most significant divergence between equity markets and the real world… or the biggest stock crash in years.

The most likely outcome? Probably an in-between, a 15%-ish correction at some point in 2026, but no dot-com crash or Black Monday; the US Government can’t (and probably won’t )let the stock market crash.

But we both know where that takes us, right? You know it, even more currency debasement.

Give a Rating to Today's Newsletter

For business inquiries, reach me out at [email protected]